Issue:

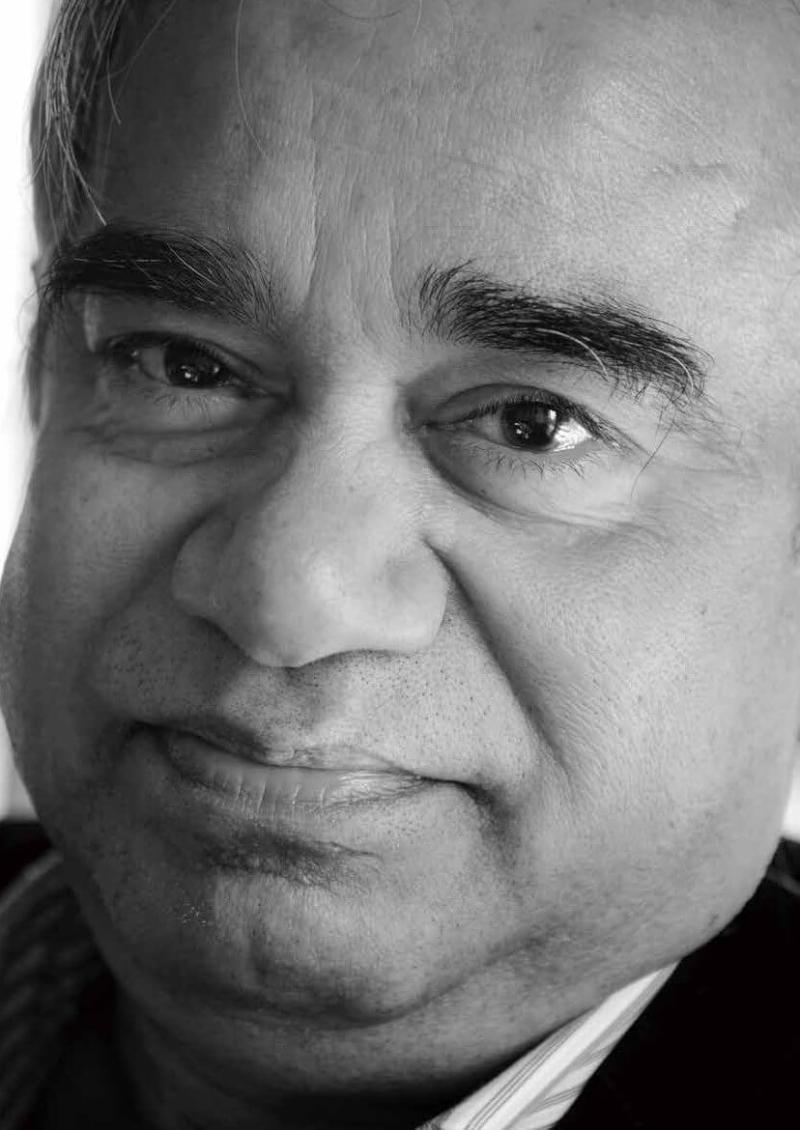

Monzurul Huq was an 18 year old high school student when he underwent his baptism of fire into journalism: reporting from the frontline of the 1971 war of independence in his native Bangladesh for an independently produced newsletter.

Having caught the media bug, Huq found himself selected in 1972 by the new Bangladeshi government for a place to study what would become his life time trade, at Moscow State University. “The Soviet Union was the first country to offer scholarships to the new nation,” recalls Huq.

While Soviet-era Russia might not seem like the obvious place to learn the craft of speaking truth to power, Huq maintains that the journalistic skills he acquired on the courses, all conducted in Russian, have stood him in good stead during his career.

“Of course there were some ideological classes as part of the curriculum, which many of the foreigners took very lightly,” he says. “For the oral exams, everybody tried to learn some Lenin quotes. If you started off with some Lenin, it didn’t really matter what you said afterwards, you would pass.

‘FOR THE ORAL EXAMS . . . IF YOU STARTED OFF WITH SOME LENIN, IT DIDN’T REALLY MATTER WHAT YOU SAID AFTERWARDS, YOU WOULD PASS’

“But the mechanics of journalism that we learned were the same; it was how you used it afterwards.”

Huq completed his degree, went on to take a post graduate course in journaism and then began a PhD. But Moscow was also where he was to meet his future wife, a Japanese exchange student. It was an encounter that would eventually lead him to Tokyo.

He first traveled to Japan in 1979, via the Trans Siberian railway and then by ship to Yokohama. On meeting his soon to be father in law, he was given a stark choice.

“He told me he wasn’t giving his daughter away to a student, so I had to start working. It was either the PhD or my wife.”

So he left Moscow soon after, and went back to Bangladesh, where he began writing for a local newspaper. “At the time, journalism in developing countries was not very well rewarded,” he says. So he had to supplement his income with other work, including working with the United Nations Information Center in Bangladesh.

However, under the regime that had been installed following a military coup in 1975, Huq says those who had been in Soviet Russia were “regarded with suspicion,” and he began to think about working abroad.

In 1990, the BBC offered Huq a fulltime position in London, working with their Bengali language service on its World Service radio network. During his four and a half years there, Huq took an MA in Japanese Studies at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, a course that includes among its alumni FCCJ stalwart Justin McCurry and former Club vice president Jonathan Watts.

His wife pushed him to look for work in Japan, and he found the opportunity to work with NHK in Tokyo on its Bengalilanguage radio broadcasts (something he still does, once a week).

“It wasn’t full time work so I contacted the leading Bangladeshi newspaper at the time to see if I could go to Japan as their correspondent. Journalism in Bangladesh was just starting to take off; so they agreed and I came to Japan in 1994.”

Four years later, the editor of that newspaper left to start his own publication, Protham Alo, and invited some of the journalists working for him to join the new venture. Huq took what he describes as “a gamble” and remains Tokyo and East Asia correspondent for the paper to this day, as well as a contributor to its English language sister, the Daily Star.

While the late development of the media in Bangladesh was a challenge early in his career, it has proved a boon in recent years as the online revolution has yet to wreak the havoc it has brought to many of the world’s newspapers.

Prothom Alo is now Bangladesh’s leading daily with a circulation of over half a million, and still growing, way ahead of its nearest rival, according to Huq. “Internet penetration is only around five percent in Bangladesh, so people still depend on newspapers, and each copy is read by up to ten people. Then there are about a million Bangladeshi expats, many of whom who read the web edition.”

Since the mid nineties Huq has also witnessed change in Japan some bad, some largely neutral and some good from the post bubble economic decline, to the shift in the numbers of foreign correspondents from Europe and the U.S. to Asia, as well as an opening up of Japanese politics and business.

“Compared to when I first came here, more people will talk to you, and more people speak English. It makes the work of journalism easier.”

Huq has become the go to man in Bangladesh for information about Japan, and is often approached by other publications, which see him as an expert on the country, a title he rejects.

“I don’t think as journalists we should be thought of as experts; our job is to collect the opinions of experts.”

Gavin Blair began his writing career a decade ago and currently covers Japanese business, society and culture for publications in America, Asia and Europe.