Issue:

INDIVIDUALS, GOVERNMENT AND THE NGO SAFECAST STRUGGLE TO ASSESS THE RISKS OF THE CONTAMINATION THAT TEPCO HAS DUMPED ON US

Two short years ago, terabecquerels, exclusion zones and Geiger counters dominated headlines in Japan and around the world. For journalists based here, they largely became our world. Today, as the two year anniversary of the second worst nuclear disaster in history passes us, news editors beyond these shores are largely not interested. The global news cycle has moved on, there is another crisis in another country and Fukushima is slowly fading from the public consciousness.

The same is happening in Japan. The headlines, such as they are, can now be found below the fold on page three; we spend more time worrying about the potential impact of Kim Jong-un's nuclear arsenal than the radiation that has already settled like an ominous blanket across our lives.

But make no mistake: while we still can’t see it, smell it or taste it, the radio active materials that escaped from the battered reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi plant are all around us.

Some former residents of Fukushima have abandoned their previous lives entirely and moved to distant places: Hokkaido, Okinawa or even further afield. “For the first year, there were so many things that were not clear and I was so anxious about radiation,” said Yuko Hirono. “I devoted many hours to researching information about safety and was careful about food and everything else.

“Initially, the government information was doubtful as they just tried not to make people panic and didn’t share any of the important details. But, looking back, I think the government was simply panicking, didn’t have good information themselves and no knowledge of how to control a critical situation.”

That was sufficient to prompt Hirono and her husband, photographer Jeremy Sutton Hibbert, to leave Japan and move to Glasgow with their five year old daughter, Hikari.

“Everybody is busy with their day to day lives and they seem to have forgotten all about what March 11, 2011, did to Japan,” she said. “I don’t think anybody believes the situation at the reactors is under control, but people just don’t pause to consider it.”

Others myself included prefer not to think about the long term impact and have plenty of other things to keep us occupied in our waking hours.

But there are groups that have emerged from the chaotic early days of the crisis and declined to adopt the ostrich’s approach to the situation. They are actively working to identify the threat that radiation poses to each of us, the “hot spots” that exist well beyond the perimeter of the government imposed exclusion zone and to provide accurate, concise and useful information on radiation levels to anyone who needs it. And they are not convinced by the explanations and data that are being provided by the government.

Safecast Japan began as a small group of individuals who became concerned after the first reactor at the Fukushima Daiichi plant started venting radiation into the atmosphere, and grew into the NGO that it is today as they tapped into their personal and professional networks.

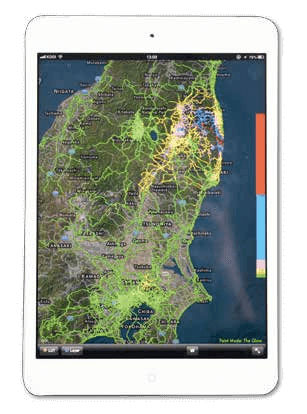

There was, says Joe Moross, an engineer and Safecast volunteer, “a lot of not knowing and a need for real information that people could use.” Using data provided by a network of hundreds of volunteers and Geiger counters which they developed themselves, Safecast now has more than 6 million measurements of radiation levels across the country, provides that data on its website and is constantly adding to its database.

“There is a considerable amount of contamination in Fukushima,” said Moross. “It’s not in amounts that will kill you immediately, but over 20 years we will see an impact. There will be people who are taken ill because of this. The question is what can be done about it now to minimize the impact.

“A lot of the cleanup is superficial and cosmetic, but that is all that is required in some parts of the region,” he pointed out. “The problem is that when they tell local residents that an area has not been heavily contaminated and there is no need for full decontamination efforts, the people get angry because they don’t believe the authorities any more. So they have to do a full clean up to make people feel better and to encourage them to come back.”

Safecast is presently carrying out tests on radiation levels before and after the decontamination efforts, but no comparative figures are available to date. And that is part of the problem.

“The government is trying to provide reassurance, but the information they are providing is just not working,” Moross believes. “It’s not what people need and it’s very paternalistic. The information is there, but it’s not particularly accessible. It’s not in a form that is readily understandable, it’s not explained and it’s not in a context that is helpful to the people who need it.”

Sean Bonner, one of the founders of the organization, agrees with that assessment. “I don’t think they care about getting the info out,” he said. “In an ideal world, the government would have seen what we are doing and copied us so then we wouldn’t have to keep doing it. And it’s easier than what they are doing.”

If there is anything positive to come out of the disaster, he said, it will be that people are quicker to react on their own initiative next time and will waste less time waiting for the authorities to help them.

Yoshiko Aoyama, deputy director of the Policy Review and Public Affairs Division of the Nuclear Regulation Authority, provided a series of internet links to NRA radiation monitoring information, as well as sites provided by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, The Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health for data in the capital and the National Institute for Radiological Sciences.

Expressing confidence that the information “has been helpful” to the public, Aoyama added that, “NRA thinks transparency is important, so we disclose information about NRA’s activities. Normally, NRA holds regular press briefings twice a week and broadcasts live coverage of our meetings and press briefings on YouTube.”

To emphasize the organization’s commitment to public health, she cited a speech by NRA Chairman Shunichi Tanaka to the Fukushima Ministerial Conference on Nuclear Safety in December, in which he said, “We will put the people’s health first. Having learned from the accident, we will steadily move toward the goal of establishing an objective and rigorous regula tory system based on hard science rather than political or economic considerations.”

But not everyone agrees that everything possible is being done. “For environmental measuring MEXT’s net worked radiation monitoring is a lame effort that nevertheless cost a lot of money,” says Azby Brown, Safecast volunteer and director of the KIT Future Design Institute. “It is not well thought out from the standpoint of what citizens want and need to know.

“The meanings of their readings are not clear enough either. People want to know how contaminated their town is, but the data available is only a reliable indicator of how contaminated it is for a few meters around each monitoring post,” he added. “The food testing data is more thorough, but still not presented in a people friendly format.”

Brown believes much of the problem lies with the “bureaucratic mindset” that afflicts government here, which also serves to make it easy for someone in a position of power to place “a bottle neck” on information. “The government should err on the side of openness,” he said. “This shouldn’t be difficult; many municipalities in Fukushima have seen the light and make almost everything available, but the prefecture and central government don’t seem to have cultures that allow this to happen.”

People in areas most seriously affected by the radiation need detailed maps of the contamination in their neighborhoods and at a scale of at least 100 meters and finer if possible that are updated frequently. A transparent process for deter mining decontamination priorities is also required, along with independent verification of the results. Equally, there is a need for clear and updated information on results of “glass badge tests” for external contamination, whole body counter tests for internal contamination and labeling of food for its radiation levels. And then the data reporting needs to be well designed and standardized, Brown points out.

“The fact is that the environment is contaminated,” he said. “No one can pretend it isn’t. It’s depressing at best. The risk debate will continue into the far future I’m sure, but the more mea surements we get of people and environment, the clearer the picture becomes.

“Most people seem to think, ‘Someone is keeping an eye on all this for us.’ In reality, it’s not clear that anyone is.”

Further information on Safecast available at: http://blog.safecast.org/

Julian Ryall is Japan correspondent for The Daily Telegraph.