Issue:

The litany of steady progress and stubborn obstacles at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant may not claim headlines four years after the fact, but there are plenty of stories to go around.

After four years and six visits (the most recent late last year) to the site of the worst nuclear accident in a quarter of a century, I find myself in the unfamiliar position of struggling to come up with a strong, news-led way to report the situation. The problems confronting its operator, Tokyo Electric Power, are familiar to anyone who has followed the crisis since it began on the afternoon of March 11, 2011.

We know that Tepco is battling to cope with the build-up of contaminated water; that some among the site’s 6,000 workers are unhappy about pay and conditions; and that the removal of melted fuel from three badly damaged reactors looks as distant a possibility as it did during the deeply unsettling aftermath of the disaster.

The near-elusive news peg reflects another fact about Fukushima that some in the anti-nuclear community will find unpalatable: that for all the public opprobrium heaped on Tepco, the utility and its vast network of contractors have made demonstrable progress since the disaster last featured prominently in the pages of the Number 1 Shimbun.

Tepco deserves credit, for instance, for reaching an important milestone last November when it completed the safe removal of 1,331 spent fuel assemblies in reactor No. 4. By the end of the year, a much smaller number of unused assemblies had also been removed from the reactor’s elevated storage pool and transported to a safer location on site.

As critics warned of catastrophe Japan’s former ambassador to Switzerland, Mitsuhei Murata, went as far as claiming that “the fate of Japan and the whole world” was at stake engineers approached the task with a sagacity that struck many of the foreign correspondents who toured the reactor just before removal work began in late 2014. “This was a risky job, so when we removed the last fuel assembly we were delighted,” Yuichi Kagami, who oversaw the fuel removal, said. “This was a big step forward in the decommissioning process.”

Dale Klein, the former chairman of the U.S. Nuclear Regu-latory Commission who heads Tepco’s nuclear reform monitoring committee, believes that a corner has been turned. The safe removal of the fuel assemblies, he said, “deserves recognition as a major technical achievement, as an advance in creating a safer environment, and as an example of how careful planning and an embrace of a safety-first culture can produce excellent results.”

No cure for the headache: What to do with the water?

Tepco has made slower progress in addressing the perennial problem of containing and treating huge quantities of contaminated water that have built up on the site. Until they do that, proper decommissioning an unprecedented technical challenge that is expected to take at least 40 years and cost tens of billions of dollars will be practically impossible, Akira Ono, Fukushima Daiichi’s manager, told foreign media organisations recently.

“The contaminated water is the most pressing issue there is no doubt about that,” Ono said. “Our efforts to address the problem are at their peak now. Though I cannot say exactly when, I hope things start getting better when the measures start taking effect.”

Officials estimate that about 400 tons of groundwater flow from the surrounding mountains and into the basements of three stricken reactors, where it mixes with a similar quantity of water that’s used to prevent melted fuel from overheating and triggering another major accident. By late last year, well over 200,000 tons of water were being stored in about 1,000 giant tanks that occupy land formerly blanketed by woods. Tepco officials say a new tank must be built roughly every two-and-a-half days.

The firm is pinning its hopes on a multifaceted approach to water containment, although it recently conceded that it will miss by several months its self-imposed March deadline for completing the treatment of toxic water. The measures include a steel barrier that will prevent contaminated water from flowing into the open sea; pumping groundwater to the surface before it becomes contaminated and the construction of a 1.4-kilometer-long “ice wall” around the four damaged reactors. Tepco is also working on ways to cover the ground with concrete and asphalt to stop rainwater from soaking into the ground.

In tandem with the ¥32 billion ice wall, the utility says it is almost ready to launch a new, improved version of its ALPS [advanced liquid processing system] water-treatment apparatus that can remove more than 60 radioactive elements. Recent “hot testing” of the apparatus has been successful, Shinichi Kawamura, head of risk communication at Fukushima Daiichi, told visiting reporters last November.

“This is a high-performance system because it uses only filters and absorbents to remove the contaminants,” Kawamura said. “The old system depended on chemical agents, which caused problems and created a lot more waste. We have confidence in this machinery.”

Many experts accept that reducing radiation levels to 1mSv/year is unrealistic

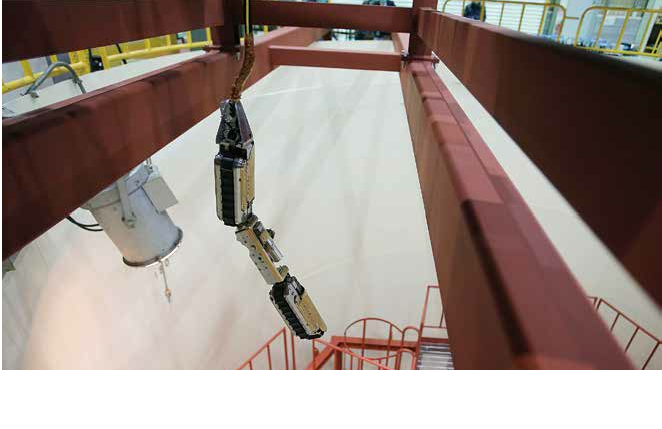

The progress Tepco and its partners have made in recent months can’t conceal the fact that radiation levels inside the damaged reactor buildings remain dangerously high four years after the triple meltdown. Earlier this year, the utility showcased some of the remote-controlled robots that have been specially designed for tasks that no human can safely perform. One newly unveiled device uses muons, a type of cosmic ray, that easily permeate light objects but are blocked by heavy substances such as uranium. Those properties should allow experts to create an image of melted fuel resting deep inside reactors Nos. 1, 2 and 3.

“This is a great example of how the innovation and cooperation from external experts is helping us overcome challenges and make progress toward decommissioning,” said Naohiro Masuda, Tepco’s chief decommissioning officer.

The human cost: plant workers and the community

Technology aside, the success of the decommissioning operation depends on the ability of the thousands of people onsite to do their jobs in safe conditions. The dangers facing the estimated 7,000 men involved in cleaning up the Daiichi plant were highlighted in January when a worker fell to his death inside an empty water storage tank. The same week, another died after equipment fell on him at the neighboring Daini plant.

The number of injuries at Daiichi, excluding cases of heatstroke, has almost doubled in the past two years. In fiscal 2013, Tepco recorded 23 injuries, while the number between April and November last year had already reached 40. The firm attributed the rise to an increase in the average number of workers at the site during weekdays, from 3,000 in early 2014 to almost 7,000 today.

In response to concerns that lack of proper rest was mak-ing Fukushima Daiichi workers more susceptible to lapses in concentration, Tepco will open a new facility in March where up to 1,200 workers at a time can rest and have meals. A new venture will provide nutritious meals for about 3,000 workers a day from April.

The utility is also under fire for failing to ensure that its contractors treat their employees fairly. Amid revelations by journalists at Reuters that some unscrupulous firms were withholding mandatory hazard allowances, four former and current workers last autumn took Tepco and several of its partner firms to court seeking millions of yen in unpaid wages.

Many Daiichi workers hail from the communities that were rendered uninhabitable by the plant’s toxic discharge. Even in villages where evacuees have been given the all clear to return, optimism is tempered by the realisation that many will never be tempted back.

The village of Kawauchi is on the edge of the original 20-kilometer no-go zone where radiation levels have been deemed low enough for residents to return, and is one of several villages I’ve revisited to monitor attempts to resettle evacuees. Dur-ing my last visit, in October, its tireless mayor, Yuko Endo, had mixed feelings about the recent lifting of the evacuation order there. “There are some of us for whom the situation has improved a little,” he said, “but there are others who have been completely unable to resume a normal life.”

Like many other places that were turned into ghost towns by radiation, Kawauchi has divided largely along generational lines. “Among elderly residents there were those who were desperate go back to their own homes and restart their normal lives,” Endo said. “They feel that they want to spend their twilight years in their own homes in their own village. On the other hand, young families with children are worried about radiation and feel unable to come back.”

Many experts accept that the official policy of reducing radiation levels to just one millisievert a year is unrealistic. What started as a non-negotiable target has now become a long-term “aspiration” amid delays in the faltering mission to decontaminate areas around homes, schools, hospitals and other public buildings.

Iitate village is one municipality that the government plans to encourage people to return to in March 2016, when they hope to win approval to lift the evacuation order. But postdisaster Iitate little resembles the village once celebrated as one of Japan’s most picturesque.

Hanako Hasegawa, a displaced resident from Iitate, says most of her 6,000 former neighbors now live in other parts of Fukushima Prefecture, with the remainder scattered across Japan. “People who visit say it’s a sad place to be now,” says Hasegawa, who works at a drop-in advice center for villagers at a temporary housing complex just outside Fukushima city. “Yet they still go back to weed the garden and tidy homes they will probably never live in.”

Hasegawa's story, and those of tens of thousands of other Fukushima evacuees, no longer makes the headlines. There is a real risk that, as each anniversary passes, the coverage will abate and their plight will be forgotten, in Japan and around the world. As foreign correspondents, we owe it to them to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Justin McCurry is Japan and Korea correspondent for the Guardian and the Observer. He contributes to the Christian Science Monitor and the Lancet medical journal, and reports on Japan and Korea for France 24 TV.