Issue:

April 2022

The Mainichi Shimbun marks 150 years of distinctive – and sometimes fearless – journalism

The Mainichi Shimbun celebrates its 150th birthday this year, making it one of the country’s oldest newspapers. Unlike many storied titles abroad that have been forced to go exclusively online to survive, the Mainichi still turns out old-fashioned paper copies while embracing the internet and social media as part of its quest to become “communicator company” that delivers news and information across a variety of platforms.

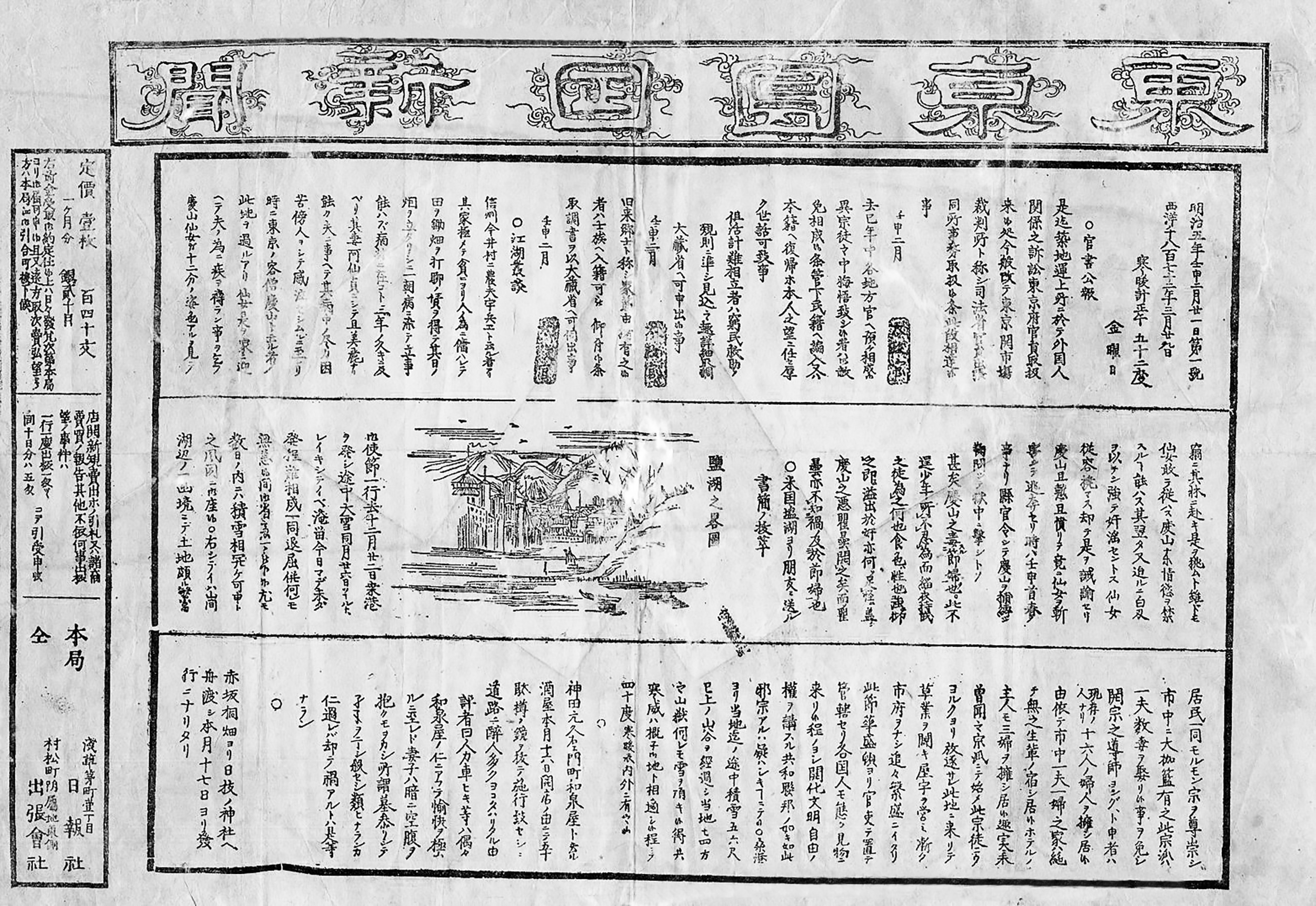

While not as ancient as the Swedish Post-och Inrikes Tidningar – established in 1645 and considered the world’s oldest newspaper – Italy’s Gazzetta di Mantova (begun in 1664) or The London Gazette (dating from 1665), the Mainichi is one of Japan’s oldest newspapers, beginning life as The Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun on February 21, 1872.

That same year, Japan’s first railroad line opened between Shimbashi and Yokohama, and the first Kyoto Exposition welcomed large numbers of Westerners, the first time so many had been allowed to visit the ancient seat of the emperor, who was by then living in Tokyo.

The Mainichi, like The Asahi Shimbun, has offices in Tokyo and Osaka. Rivalry between the two papers in the early years was always fierce, especially in Osaka, where both had bigger circulations than they did in Tokyo. In an April 1918 report about Japan’s journalism, University of Missouri professor Frank L. Martin noted both newspapers had circulations of 300,000 in Osaka, while the Tokyo circulation of the Mainichi was about 175,000 versus the Asahi’s 180,000.

During World War II, Japan’s media was controlled by the state, so getting accurate reports from abroad was extremely difficult. Within the Mainichi, resistance to censorship took the form of what would become known as the "Benjo Press". As Mark Schreiber detailed in the June 2020 issue of The No. 1 Shimbun, a converted women’s restroom in the Tokyo Mainichi housed a secret shortwave radio that caught overseas broadcasts, giving reporters and editors notice the war was going far worse for Japan than military and government officials were admitting.

The Mainichi got the first major postwar scoop of any paper when, on February 1, 1946, it published a draft of the new constitution, then being debated in the Diet. The following day, in a memo to Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur, Brigadier General Courtney Whitney, Chief of Government Section, noted that the draft, as reported by the Mainichi, was extremely conservative in nature and left the status of the emperor virtually unchanged. MacArthur ordered a redraft and the result would be a very different constitution, written largely by the American occupiers, that included ideas loathed by Japan’s conservatives, including equal rights for men and women and a change in the status of the emperor, from living god to symbol of the state.

In 1972, the Mainichi scored another scoop when Takichi Nishiyama revealed Japan and the U.S. had a secret agreement on the cost burden for Okinawa’s reversion to Japan, in which Japan paid the U.S. for land that had been used by U.S. forces. The Japanese government denied the existence of such a pact. Nishiyama, who received proof of its existence from a secretary at the foreign ministry, was arrested and convicted for revealing the information. In 2009, a former foreign ministry official told the Tokyo District Court there had indeed been such a pact, but Nishiyama’s reputation had already been destroyed.

More recently, the Mainichi has been the target of regular attacks by pro-corporate, anti-union, historical revisionist and right-wing activists and politicians ranging from former Osaka governor and Nippon Ishin co-founder Toru Hashimoto to former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The paper has been a particularly sharp thorn in Abe’s side.

In 2016, reporter Satoshi Kusakabe led a Mainichi team that revealed the Abe’s Cabinet Legislation Bureau had not kept records of its deliberations on how to reinterpret Article 9 of the constitution for collective self-defense. The team won the Japan Congress of Journalists’ grand prize. Kusakabe and his colleague, Ken Aoshima, also reported on Abe’s push to pass a controversial state secrets act and the constitutional problems that raised.

They also hounded Abe over his lavish publicly funded cherry-blossom viewing parties with a series of highly critical reports, which were complied into a 2020 book, “Dirty Cherries”. Kusakabe and his team won the Ishibashi Tanzan Memorial Journalism Award last year for their coverage.

Today, the Mainichi’s circulation stands at around two million copies a day and continues to fall. Like all newspapers, it faces an aging, declining readership for the print edition and tough economic and financial challenges posed by online competition, much of it free to view. The pressure to court large, powerful advertisers and pander to their agenda has never been greater.

But at a time when more people distrust the news media, believing they are little more than mouthpieces for the rich and powerful, Mainichi president Masahiro Maruyama said, in commemorating the newspaper’s milestone, that its future direction would be determined by “listening to the small and silent voices that lurk in everyday life”. Here’s hoping that philosophy remains in the Mainichi newsroom for another 150 years.

Afterword

A word about the Mainichi’s English-language operation, The Mainichi Daily News, which celebrates its 100th anniversary in April.

Between 1994 and 1997, I worked as a full-time translator and reporter at the MDN’s Osaka headquarters, covering Kansai and national news as well as the Hiroshima Asian Games and the 1995 Osaka APEC conference. I also traveled on assignment to Europe and Washington. Like its vernacular parent, the MDN newsrooms in Tokyo and Osaka had an eclectic cast of characters who were, by turns, cynical, funny, brilliant, dedicated, and highly opinionated. I miss them all.

The Mainichi organization gave us a fair degree of freedom over what we proudly saw as a “community newspaper”. Or, as my editor put it, “your hometown paper”. Wit, dry humor, subjective phrases, and references only longstanding readers would understand were not always openly encouraged, at least in the news section. But neither were they discouraged in the manner of our rivals, whose bland writing styles we derided as being “all the news without flair or flavor”.

Of course, even at the MDN, we were aware of The Mainichi Shimbun’s reputation within the industry as penny pinchers. When I saw the expense accounts that Japanese reporters at the Yomiuri, Nikkei, and NHK were enjoying, I realized the reputation was deserved. But that was a point of pride among Mainichi reporters. Get the story by underspending, not overspending, your rivals. And while Mainichi Shimbun employees always complained that their salaries were lower than those of their rivals, they were usually solidly middle, even upper-middle class, wages.

The MDN was never as popular in Tokyo, where The Japan Times ruled, as it was in Kansai. Today, the MDN is online only and reaches people in Japan and beyond in a way the paper I worked for in the pre-internet days never did. But the choice of articles shows that, whatever the editorial leanings of the competition or the demands of advertisers, the MDN has, unlike most of its competitors, less interest in introducing, explaining, or propagating Japan to the outside world and more interest in reporting the country as the Mainichi reporters see it. Which often turns out to be the Japan that many of us at FCCJ, if not readers elsewhere, recognize and appreciate.

Eric Johnston is Senior National Correspondent for The Japan Times. The views expressed above are his own.