Issue:

The leader of an effort to bring accountability to the Fukushima nuclear accident looks back at the effects of the historic report

Can a 4kg, 1400-page report change a country?

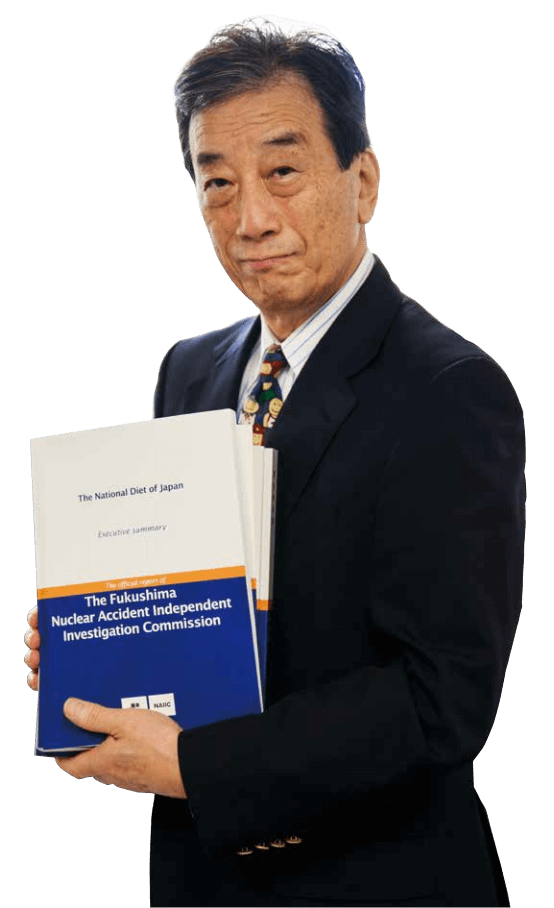

by Dr. Kiyoshi Kurokawa

On July 6, 2012, I was to appear before a crowd of journalists at the FCCJ to announce the delivery to Japan’s National Diet of the report by the Diet’s own Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission (NAIIC). I was tired but pleased. It was the first such commission in the history of democratic Japan, and the completion of the report a short six months after receiving our mandate was the result of sometimes frantic but always incredible efforts made by my assembled team of experts.

Although the reaction of the Diet legislators was (not unexpectedly) rather cool when I had handed over the report the previous day, my team was extremely proud of the depth of the report. I was looking forward to the press conference because the commission had received a lot of attention from the global media. We had been surprised by the number of journalists that attended the many commission hearings and press briefings (which vindicated our decision to avoid the normal Japanese “press club” system, and to include simultaneous interpreting).

‘ACCOUNTABILITY’ HAS MORE WEIGHT THAN THE WORD ‘RESPONSIBILITY’ — EXCEPT IN JAPAN, IT SEEMS.

At the press conference, much was made by some journalists of the differences in the global version as opposed to the Japanese version, especially the statement about the accident being an incident “made in Japan” my attribution of the causes of the accident to some of the conventions of Japanese culture. But those who read the Japanese version carefully, I believe, found the same conclusions and the same nuance.

Thanks to the global media, and the world wide public interest in the shocking accident, our commission’s report turned out to be highly valued overseas. Not only was the media coverage extensive, but the scientific community took notice. I (as leader of the team) was awarded the AAAS Scientific Freedom and Responsibility Award by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. I also humbly accepted being called one of the “100 Global Thinkers” by Foreign Policy magazine.

But while accolades are always appreciated, they were not the intention behind our report. We believed that exposing loose governance and lack of vigilance by the Japanese authorities and Tepco would galvanize the various arms of the nuclear “village” in Japan to rethink their way of operating. We also believed that it would help gain trust from the rest of the world by showing Japan’s determination to deal with the disaster.

Unfortunately, although the report has now been in the hands of the Diet, the press and the general public for some 14 months, I’m afraid that it’s hard to be optimistic.

Most of the Japanese public doesn’t understand the importance of checks and balances in a democratic government with three branches. So there’s little public pressure on the government for prompt action.

That leaves the government free to move at its own sluggish pace, even in moments of crisis. The commission didn’t receive our mandate until nine months after the accident. Then after our delivery six months later, it took another nine months for the first response to the seven recommendations that we made.

Just half of one recommendation to set up a Diet committee to supervise nuclear regulation was adopted by the lower house. On April 8, 2013, and nine of our ten commissioners appeared at eight hours of hearings held by the newly created Special Committee for Investigation of Nuclear Power Issues. With the LDP in power now, we understand that acceptance of our recommendations has become even more political.

And that’s pretty much been it so far. There was no response at all by Tepco or anyone else in the nuclear industry despite all of our detailed critical analysis of their actions leading up to and following the accident. In other words, the problems we highlighted in the report have yet to even be acknowledged, much less dealt with.

I had hoped that what made our commission such a success the commitment to openness, transparency and global awareness might have some affect on the way the nuclear elite did business. But it is now impossible to believe that the situation is getting any better, and the state of the Fukushima Nuclear Plant is a case in point. The briefings on the situation by Tepco are indecipherable. They don’t even try to make themselves understood, by either the Japanese public or the international community. Their statements always seem to imply that they think this is all someone else’s problem that landed on their plate purely by accident.

The information from the central government is also opaque, as are their plans for future handling of the crisis. It’s fine for our prime minister to extol the safety of the country in front of the world, but we would hope he could back up his claims with scientific proof.

Curiously, the Japanese media has also lost its courage, with less and less critical coverage. (Tokyo Shimbun has been a rare exception, with fair and timely reporting on relevant issues.) This has left the people of the nation without a voice. Even if a journalist has information of critical importance, he rarely divulges it for fear of endangering his job or position. This deception is counter productive and will only lead to a loss of faith from the international community. I wish the Japanese press would pressure the government and Tepco the same way that the foreign press tries to do.

IN THE MIDST of these immovable barriers of the present system that seem to heighten the difficulties faced in this nuclear disaster, I still find moments of hope, and several came directly as a result of the NAIIC commission.

They came from people who have gone through a dramatic change in their careers after participating in work at the NAIIC. One of them is Tsuyoshi Shiina, who went on to become a Diet member, and is a member of the Diet committee on nuclear oversight mentioned above. Another is Satoshi Ishibashi, a senior team manager who launched a project with a team of dedicated young people called, “The Simplest Explanation of the National Diet of Japan Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission.” It’s a website that intends to make all the complicated scientific discoveries made by the commission understandable to the general public. It’s an excellent resource, and has recently added a series of videos that illustrates the findings in a very visual, simple way. It’s only in Japanese, but an English version is now being produced.

Yurina Aikawa is another of our team who actually left behind a budding career in order to join NAIIC. She had been working at one of Japan’s major papers, doing research on the nuclear accident, before she came to us. After the commission was dissolved, I asked her about her plans; she told me that she was going to continue her research on the victims of the disaster on her own. I had been surprised at her leaving her newspaper career to join us, and I was even more moved with this decision.

In August, the results of her research were published in a report titled Hinan Jakusha (“The vulnerable evacuees”) that documents the experiences of many victims whose fates are out of their control. It is an excellent, powerful book and I was pleased to be able to write a comment for it.

Individuals like Shiina, Ishibashi and Aikawa are helping to make sure that the nuclear accident and its victims remain on the nation’s agenda. Given the recent political and social climate, this is not easy to do. But as much as I hail their efforts, they do not in any way excuse the continued floundering by everyone involved in the governmental and industrial efforts since this crisis began.

At a lecture at the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS) earlier this year, I pointed out how the meaning of the word “accountability” has been lost in its translation to Japanese. I explained that in Japanese, accountability is translated as “the responsibility to explain,” rather than the true meaning, which is “the responsibility to carry out the duty one has been given.” “Accountability,” in fact, has more weight than the word “responsibility” except in Japan, it seems. But that has to end. We need to hold those responsible to account.

In the NAIIC report, accountability makes up a large part of our recommendations, though they are largely, and unfortunately, ignored. And since I believe that our recommendations would go a long way in not only helping us get beyond the present situation but would actually help us learn from it, I’m going to repeat them.

What we still need is an independent international committee, committed to scientific principles and transparency, that will come up with solutions to the problem and make proposals to the government, which in turn will make decisions and execute these solutions. We need a plan of action that deals with the mid and long term plans of the Fukushima disaster, and we need it to be shared with the world.

Independence, transparency, public disclosure, adherence to scientific principles and an international approach are a must as a first step towards the recovery of trust in this globalized age.

It is because of these factors that NAIIC was so highly respected and earned the trust of the global community. There is an urgent need for the public to understand this and to demand the same from their government and all the other parties to the nuclear accident in Fukushima who betrayed them.

photo by SAID KARLSSON

The entire NAIIC report is available online in English from the National Diet Library archives at http:// warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info: ndljp/pid/3856371/ naiic.go.jp/en/

Kiyoshi Kurokawa is Academic Fellow at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS): www.grips. ac.jp/en/. He blogs at www.kiyoshikurokawa.com/en/.