Issue:

Oh crap! We’ve got the Olympics. Hang out the bunting. It’s a good thing, right?

In the days following Tokyo’s successful bid to host the 2020 Olympic Games, media reports in Japan reminded people here of the cost of the March 11, 2011, earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster. Over 16,000 people died with more than 2,000 still missing, presumed dead. The dead won’t benefit from the Olympics, but the living are still struggling to benefit from the world’s generosity following the disaster. Nearly 300,000 people in Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures are still living in temporary housing. At this rate, the Olympic athletes will have accommodation before the disaster affected homeless of Tohoku.

But while the shadow of Fukushima hung over the vote, it has to be remembered that it was a vote on Tokyo not Fukushima and not Japan. The Olympic Games are awarded to a city, not an area or a country, so the response from Tsunekazu Takeda, the head of Tokyo’s Olympic bid, made sense: “Radiation levels in Tokyo are still the same as in London, New York and Paris.”

Having won the Games, Tokyo can now, hopefully, detach itself from the worries of Fukushima. Winning the Games is a cause for celebration, for both Japan and Tokyo. Japan’s and Tokyo’s history with the event has had its ups and downs.

Tokyo was first awarded the 1940 Summer Olympic Games but that was derailed by World War II. You might wonder what the International Olympic Committee was thinking awarding successive Games (Berlin hosted in 1936) to two belligerent, warmongering states.

The IOC remembered Tokyo and curiously forgot all about the war when it awarded the city the 1964 Games (Tokyo also bid for the 1960 Games, which went to Rome instead). And while some might have wanted to punish Japan for its conduct pre 1945 notably China and the two Koreas, who were still politically alienated from Japan the 1964 Olympics served as a symbolic reintegration of Japan into the civilized world. And the country responded with a dynamic, high-tech celebration and a completely restructured city. Though North Korea boycotted, Japan’s only hint of politicking came when the Olympic Flame was lit by runner Yoshinori Sakai, who was born in Hiroshima the day the Americans wiped it out with an atomic bomb.

Japan got another Olympics eight years later when Sapporo hosted the Winter Games, and the country hosted the Winter Games again in 1998 in Nagano. With the 2020 Games, Japan will have hosted four Olympic Games, third overall and second most behind the United States in the postwar era.

While the Winter Games carry a certain amount of prestige, Japan has been chasing the Summer Games for some time. Nagoya was stunned when it lost out to Seoul for the 1988 Games as the IOC opted to send the event to a country ruled by murderous dictator Chun Doo Hwan just a year after he had ordered the slaughter of hundreds, maybe thousands, of civilians in the southern city of Kwangju.

Of course, the selection of the host city has often been troubled by the exchange of favors and cash. A number of Olympic host cities (Salt Lake City, anyone?) have been accused of excessive “generosity” including Nagano whose records mysteriously went up in flames. In recent years, the IOC has cleaned up its act by making changes to the bidding process, allowing its voters to concentrate on the merits of the bidding cities rather than the perks of their positions.

For the 2016 summer games, the Japan Olympic Committee decided to go with Tokyo rather than Fukuoka. Tokyo responded with an impressive, beautiful bid that earned the top rating from the IOC after the initial evaluation of the bidding cities. Tokyo’s advantages were clearly superior to those of its rivals (Rio de Janeiro, Madrid and Chicago), claiming it could provide “the most compact and efficient Olympic Games ever.” But when the votes came in, Tokyo was third in the first two rounds and was eliminated behind Rio and Madrid; the latter in turn was trumped by the allure of Brazil and the attraction of seeing the Games in South America for the first time.

So what changed for this year’s selection process? Bids from Rome, Baku and Doha were eliminated early on, leaving Tokyo, Madrid and Istanbul. All three had been persistent in their attempts to host. (Madrid had actually won the first vote for 2016.)

All had their own major attractions. Madrid presented a very economical bid and was attractively placed globally for the important broadcasting zones of Europe and the Americas. Istanbul had similar momentum to Rio in that the Games could be held in a new area, a different (Muslim) culture and in a city that straddles Europe and Asia. Tokyo, mean while, had the money, the technology and the best layout for the Games. They all had something going for them.

IF TOKYO WANTS TO LIVE UP TO ITS PROMISES IN 2020, IT NEED LOOK NO FURTHER THAN 1964.

But the news over the past year hit them all hard. The economic crisis really started to bite in Spain, which saw unemployment reach 25 percent. And some saw Madrid’s $2 billion budget half that of Tokyo’s as a sign of weakness. Olympic budgets invariably double, so there were also worries about whether Madrid would be able to keep up the payments. Spain probably led in the affability stakes with Prince Felipe and Juan Antonio Samaranch Jr., the erudite son of the former head of the IOC. But it was obvious that Madrid’s presentable façade hid a weak foundation.

Istanbul’s budget was a whopping $19 billion, which instantly raised red flags. Imagine that doubling. Voters also worried about the infrastructure, as every thing would have to be built. Still, that may not have proved fatal until a wave of riots hit the city in the months leading up to the vote, in addition to the civil war in neighboring Syria.

Fukushima definitely spread a cloud of doubt over Japan but, unlike the crises in Spain and Turkey, the problem hasn’t yet directly affected the bidding city. And Tokyo did an admirable job of learning from previous mistakes.

Bids need an emotional tone, and faces that click with the IOC delegates. The bid for 2016 was seen as spectacular from a technological point of view, drab from an emotional one. The push by then PM Yuko Hatoyama and then governor Shintaro Ishihara were limp at best; the message seemed to be nothing more than “We build good cars.”

Ishihara’s successor as governor, Naoki Inose, wasn’t a great improvement and made a couple of serious gaffes earlier this year, but he didn’t carry Ishihara’s baggage. And, surprisingly, even Abe came over as a likeable chap in his presentation made in much better English than Hatoyama’s.

As Abe shut the door on the horrors of Fukushima with his glib pronouncement “there’s nothing to see there,” paralympic athlete Mami Sato, also speaking in understandable English, opened the door to the emotions of the earthquake and tsunami, recounting how she spent six days won- dering if her family in Miyagi were dead or alive. Sato emphasized how Japanese athletes had embodied the Olympic spirit with countless visits to those affected by the disaster – and voila! . . . Tokyo’s bid had its emotional connection. Following a good speech in English by Olympic fencing medallist Yuki Ota, Tokyo got two delightful speeches in French from HIH Princess Takamado and former news presenter Christel Takigawa.

In the end, the mere possibility of disaster/Armageddon trumped the ongoing problems elsewhere. Madrid lost the run off from the first round after tying with Istanbul; Tokyo overwhelmed Istanbul in the final, 60 to 36 (and embarrassing the editors of this magazine, who seemed to believe in last June’s issue that the spectre of Inose and Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto would sink the Tokyo bid).

For further reasons for Tokyo’s win, insiders point as well to a well-oiled PR campaign that launched its candidature in London, riding the coattails of a country still buzzing from its own wildly successful Olympics. It also campaigned strongly on the domestic front after the IOC had taken a dim view of support figures for 2016 that showed less than half of Tokyo’s population supported the bid. Of course, half of 35 million is still rather a lot, but the perception was negative and had to be put right. One of the major breakthroughs was the post London Olympics parade of medallists through Ginza, which attracted half a million people and put the feel good factor back into Tokyo. An IOC poll saw public support at 70 percent at the beginning of this year and a government poll saw that figure rise to 92 percent 10 days before the vote.

So what does it mean for Tokyo and Japan?

From a sporting point of view, the Olympics represent the ultimate goal for many athletes and a home Olympics focuses and intensifies their aim. The host country usually increases the number of athletes and the number of medals. In the 2012 games, for example, Britain fielded 541 athletes for 65 medals and 29 golds, whereas in 2008, it won 19 golds and 47 medals overall with 313 athletes.

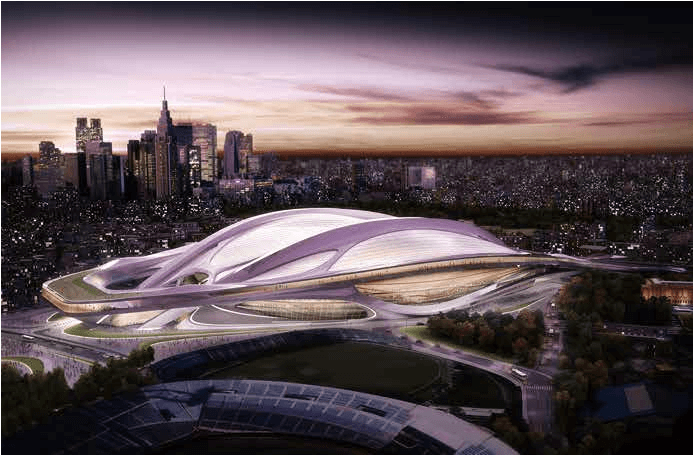

But there are other very visible results, like the transformation that Tokyo underwent prior to the 1964 games. The Olympics provided the impetus to get things done as Tokyo placed priority on improving infrastructure that would assist the Games, including “road, harbour, water works development on a considerable scale over a significant area of the city and its environs.” Tokyo venues such as the National Stadium (soon to be rebuilt), Komazawa Sports Park and Yoyogi Gymnasium are still being used today.

If Tokyo wants to live up to its promises in 2020, it need look no further than 1964. Avery Brundage, the president of the IOC in 1964, was fulsome in his praise: “No country has ever been so thoroughly converted to the Olympic movement. … Every difficulty had been anticipated and the result was as near perfection as possible. Even the most callous journalists were impressed, to the extent that one veteran reporter named them the “Happy” Games. This common interest served to submerge political, economic and social differences and to provide an objective shared by all the people of Japan. … The success of this enterprise provided a tremendous stimulus to the morale of the entire country.”

Tokyo has just taken the first step. It has a lot of promises to live up to, but it also has a past to learn from. Perhaps it will lead to regeneration on a broader scale. As Olympic host and capital city, it has a responsibility to do things right. What could possibly go wrong?

Fred Varcoe is a freelance writer based in Chiba and has written about sports for The Japan Times, the Japan Football Association, UPI, Reuters, dpa, The Daily Telegraph, Sky Sports News, Golf International, Volleyball World, the International Volleyball Federation, Time Out and others.