Issue:

During the post-war Occupation, one Tokyo Correspondents’ Club member played two roles one as a member of the press with his eye on the news; the other a priestly one with his eye out for his church.

At the end of the Second World War in August 1945, the occupation of Japan commenced, under the command of GHQ (General Headquarters). Journalists from various countries began arriving in Japan, and the Tokyo Correspondents’ Club, the forerunner of the FCCJ, was organized in October of the same year. It was located in the old five-story Marunouchi Kaikan building, an address whimsically nicknamed No. 1 Shimbun Alley.

Though the bombings had left much of Tokyo in ruins, the press club was equipped with a bar, dining room, and accommodations facilities, and various people, Japanese and foreigners of all stripes, poured in and out of its doors throughout the day. John Morris, a British correspondent for the BBC, described the club in his memoirs titled The Phoenix Cup, as “a cross between a waterfront sailors’ bar and a brothel.”

“Drunken brawls were frequent,” wrote Morris. “And there were occasions when firearms were discharged in the lounge. But at this time conditions were quite abnormal. There was absolutely nothing to do in Tokyo after dark, and drink was plentiful and cheap.”

The sleeping rooms had an occupancy of five persons, but Morris found it difficult to maintain privacy, as some members brought girls into the rooms. “It is very easy to appear priggish in these matters,” he wrote, “especially to Americans, whose attitude to sex is so different from our own . . .but I do feel very strongly that the sexual act is something which should only be performed in private.”

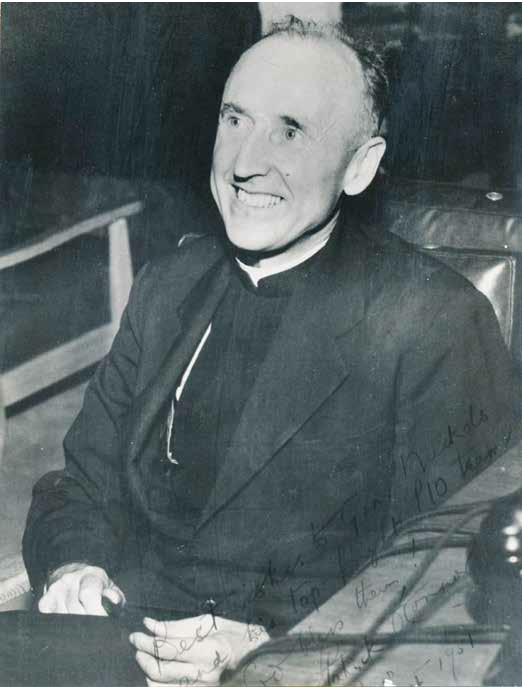

Given the moral atmosphere of the premises, one of the more unusual presences was Irish correspondent Patrick O’Connor, a reporter for the National Catholic News Service, who also happened to be an ordained priest. United Press correspondent Albert E. Kaff, who was later to serve as Club president from July 1967 to June 1968, was quoted in the Club history book Foreign Correspondents in Japan as saying, “Father O’Connor sometimes objected to the profanity and sex stories that he heard in the Club’s lounge and its adjoining bar. So, in an effort to rehabilitate his colleagues, the good father presented the Club with a Bible…”

Born in Dublin in March 1899, O’Connor had studied English literature, philosophy and other subjects at the National University in Ireland, and was ordained into the Society of St. Columban in 1923. He subsequently began writing for The Far East, a leading Catholic news magazine, and months after the end of the war, in January 1946, came to Japan as the National Catholic News Service’s Far Eastern correspondent. He was to file many stories about the country under the Occupation, one of which was to have unexpected results. The particulars of this story can be found in documents at the Rockefeller Archive Center in Westchester County, New York.

On Jan. 25, 1951, John Foster Dulles, a special envoy of President Harry Truman, arrived at Haneda airport. Dulles, who was to be appointed Secretary of State in the Eisenhower administration, came for the purpose of negotiating, together with General Douglas MacArthur, a peace treaty with Japan. Also disembarking from the plane with Dulles was a handsome American, John D. Rockefeller III, a member of the wealthy Rockefeller family, whose role in the Dulles mission was to serve as a cultural advisor.

During his stay in Japan, Rockefeller met with various Japanese intellectuals, such as authors, academics, religious leaders and others. Upon his return, he produced a report that proposed cultural exchanges between the U.S. and Japan.

On Feb. 22, immediately after the American contingent’s departure, O’Connor filed a story from Tokyo about Rockefeller’s meetings with several Christians in Japan none of whom, as it turned out, were Catholic. The story was to appear in several Catholic publications under the headline, “No Catholics among ‘religious leaders’ consulted on Japan visit by J.D. Rockefeller 3d.”

By the middle of the following month, the New York-based National Conference of Christians and Jews sent a letter to Rockefeller, based on O’Connor’s article, requesting clarification. Rockefeller promptly consulted with people in his circle and John Foster Dulles, and on March 20, sent a letter to O’Connor in Tokyo.

“Readers of your article may assume that I deliberately refrained from talking with any Catholics during my stay. Such was not the case. I should have welcomed Catholic representatives in my discussions . . . I should appreciate now an opportunity to obtain a representative viewpoint of your Church on the problem of cultural exchange and if it is possible to send your views to me, or arrange to have them sent by another representative Catholic, I should be sincerely grateful.”

So Rockefeller was clearly disconcerted by O’Connor’s article. Was O’Connor satisfied with this clarification? O’Connor’s reply, dated April 7, provides a hint to his reaction. He wrote: “I recognize, of course, that you did not intend to slight the Catholic Church in Japan, or elsewhere. But the omission occurred and I felt that it deserved to be reported. I reported it objectively, without ascribing any motive . . . Your aides in the Diplomatic Section of GHQ should have had no difficulty in identifying the members of the missionary group. . .”

“Father O’Connor sometimes objected to the profanity and sex stories in the Club. So, he presented the Club with a Bible.”

Concerning Rockefeller’s request to provide advice related to cultural exchanges between Japan and the U.S., O’Connor added, “I am not qualified to speak as a representative of the Catholic body in Japan. My function is that of a correspondent in the Far East for the Catholic press.”

But was this, in fact, really the case? According to documents in the Catholic University of America’s archives in Washington D.C., it is obvious that O’Connor was active at that time as a lobbyist for the Catholic Church in Japan.

For example, when two American Catholic bishops, John F. O’Hara and Michael J. Ready, visited Japan in July 1946, O’Connor prepared materials and arranged for the two bishops’ press conference. He also argued in support of a plan to use religious agencies within Japan for the distribution of supplies sent by religious agencies in the U.S., and sent Gen. MacArthur a long memo concerning this. And he made a request to the Japanese government for a larger allocation of newsprint to be supplied to a Catholic newspaper.

Catholic officials in the U.S. seemed to be happy with his double career. A 1948 document found in the National Catholic Welfare Council collection at the Catholic University of America’s archives states: “His news dispatches have been of highest caliber, but even more important have been the ‘sidejobs’ he was able to do for the Church.”

In the excerpts of his report that accompanied the above document, however, it becomes clear that there were some in the news business who wondered about his ability to operate both as a cleric and a newsman. O’Connor noted that there were those who were suspicious of his activities: “Everybody, Communists included, knew that I am a priest. The combination of priest and correspondent was unprecedented apparently, and occasionally I could sense some doubt or suspicion in some Americans was I really a correspondent or an ecclesiastical agent using the status of a correspondent for some ecclesiastical stratagems? This suspicion may linger with some leftist newspaper men.”

O’Connor wore two hats, so to speak: that of a foreign correspondent and that of an agent for the church. As far as GHQ policies were concerned, the advantages of this arrangement outweighed the disadvantages. Though not a Catholic himself, MacArthur viewed the practical use of the Christian religion as one method for democratizing Japan. In fact, in December 1945, at a meeting with Archbishop Paul Marella, the Apostolic Delegate to Japan, MacArthur had remarked:

“The Japanese people are witnessing a shattering of their faith in their gods and looking for something new to fill the vacuum created by the abolition of Shintoism as their state religion. To me it seems as if the Catholic Church alone can offer the Japanese people something to fill this spiritual vacuum. The organization of the Church, its moral teachings and its ritual are perfectly suited to the Japanese character and I would welcome any assistance given me by the American Hierarchy. . . .”

How much MacArthur’s appreciation of the Church helped O’Connor in his reporting (and lobbying) duties is hard to ascertain. MacArthur’s propensity for avoiding direct contact with the mass media was well known, and during his tenure in Japan he only visited the press club on a single occasion in March 1947. But O’Connor was one of a miniscule number of correspondents who were granted an exclusive interview with the General.

Patrick O’Connor died in July 1987 at the age of 88. What became of the copy of the Bible he presented to the Club, in the hope of reforming his wayward colleagues? Alas, according to the Club history, “. . .for several years the Good Book was prominently displayed next to rows of bottles on the back bar . . . But few of his colleagues asked the bartender to hand them the Bible.”

Nevertheless, Kaff recalled, “No one was offended by his evangelism in the Press Club bar, and Patrick always remained a member of the gang, well liked and admired.”

Eiichiro Tokumoto, a former Reuters correspondent, is an author and investigative journalist. The Bible in this story is missing from the library shelves, so he asks that anyone with knowledge of its whereabouts contact the FCCJ librarian.