Issue:

July 2025

U.S. B-29s prepared for the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with dozens of deadly raids on Japanese cities

As the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II approaches, I frequently find myself impressed by research that reveals new insights into some of the war's major events, as well as providing tantalizing clues to many unanswered questions.

I was reminded of this by an article by Samuel Hawley in the Washington Post on 15 May. Hawley touched on the origin of the namesake of Enola Gay, the B-29 that dropped the uranium bomb "Little Boy" on Hiroshima.

It has been common knowledge that Enola Gay Tibbets was the mother of Col. Paul Tibbets, who piloted the B-29 aircraft that ushered in the atomic age. Her name, according to Hawley, originated from the heroine in an 1886 novel by Mary Young Ridenbaugh titled Enola: Or, Her Fatal Mistake. Enola, Hawley noted, was created by spelling "alone" backward.

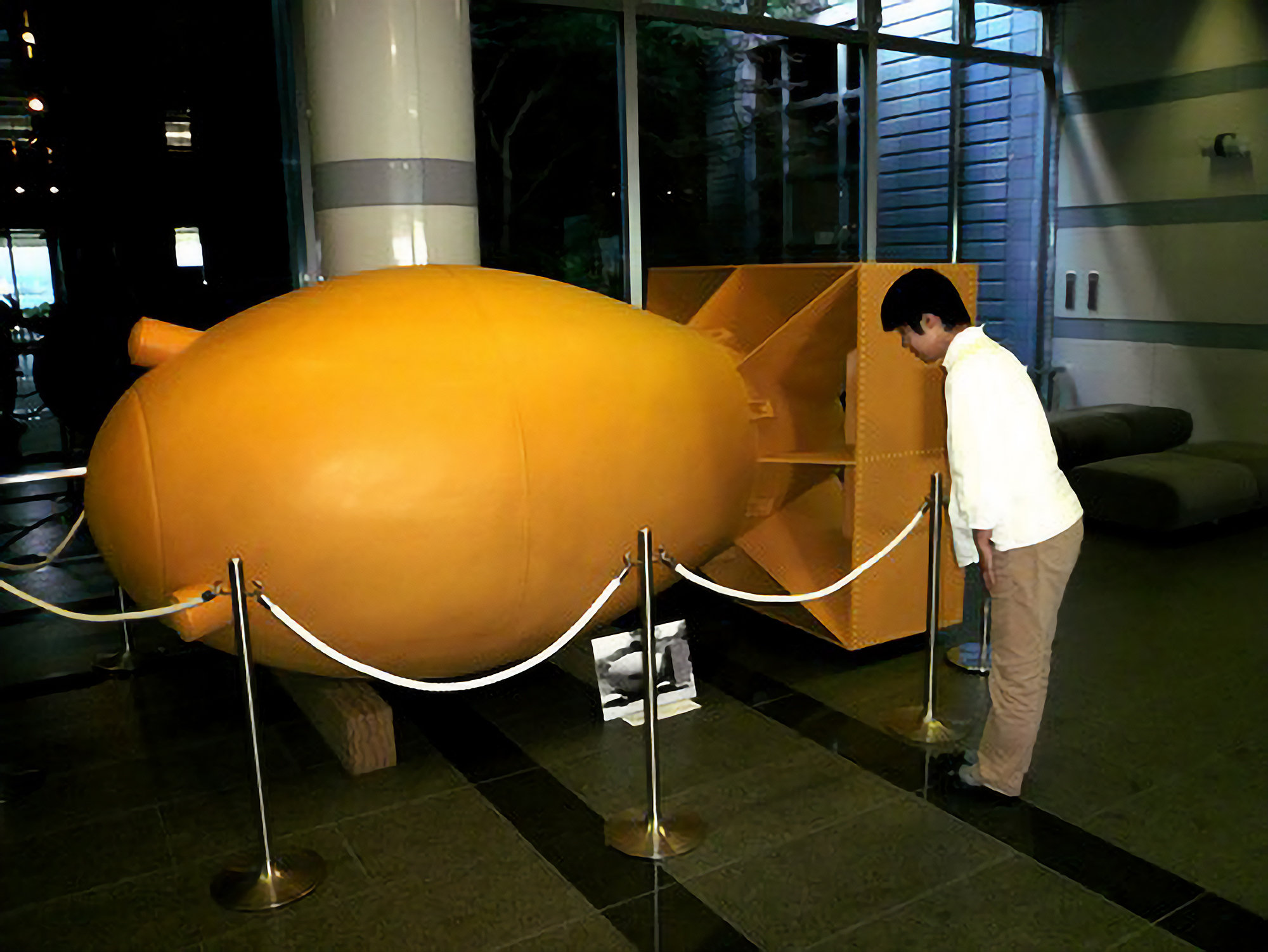

I also learned that in the runup to the bombing of Hiroshima, the B-29 with serial number 44-86262, yet to be christened Enola Gay, flew two practice missions over Hyogo and Aichi prefectures. The bombs it dropped were obviously not atomic; they were referred to as “Pumpkin bombs” because of their ellipsoidal shape and yellow color. They have also been called A-bomb practice bombs. In Japanese they are known as genbaku mogi bakudan (mock atomic bombs), or mogi genbaku for short.

With roughly the same weight and dimensions of "Fat Man," the plutonium bomb dropped on Nagasaki, the Pumpkin bombs were among the most destructive conventional bombs used in World War II.

The missions flown by Enola Gay on 24 and 26 July were piloted by Captain Robert A. Lewis, who on August 6 would serve as the co-pilot to Colonel Paul Tibbets on the mission over Hiroshima.

To maintain secrecy, Lewis, like the other pilots and crew members of the 509th Composite Group based on Tinian, Northern Mariana Islands, had not been briefed on the specific purpose of the practice flights - and would not be told until August 6. The crews were simply assigned targets and given instructions to release the massive 4.5-ton bombs from an elevation of around 30,000 feet, and then steer away sharply after release.

Flown at high altitudes by solitary aircraft, the Pumpkin bombs were dropped on widely dispersed targets so as not to attract undue attention. To the hard-hit Japanese defenders at the time, the Pumpkins were just another of the various types of bombs that had been raining down on Japan's cities and factories, and any particulars concerning their design, purpose and destructive power were left largely to speculation.

Here is how the Chubu Nihon Shimbun of July 27 reported air raids conducted the previous day:

On the 26th, more than 10 enemy B-29s were operating in the Tokai and Hanshin regions one after another; but some single B-29s were quite tricky, pretending to be just a reconnaissance plane, but dropping bombs on Nagoya and Osaka, aiming to destroy morale. The damage was of course insignificant, but not taking refuge and thereby causing needless deaths, or forgetting to extinguish fires and thereby reducing the nation's important fighting power to ashes, constitutes aiding the enemy. Strong nerves mean acting with utmost caution.

Another Pumpkin bomb dropped by Enola Gay, on July 24, 1945, detonated so far from the Kobe Steel factory, its intended target, that the spot where it impacted was not located until late 2023.

The bomb's impact point was determined by Koki Nishioka, a 27-year-old graduate student at Kobe University's Faculty of Law. Nishioka, reported the Chugoku Shimbun on November 28, 2024, had become interested in Pumpkin bombs after viewing a display panel at the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Museum.

After moving to Kobe, Nishioka began to research one of four Pumpkin bombs targeting the Kobe Steel factory on 24 July whose impact point remained unknown. Referring to eyewitness diaries and aerial photographs taken after the war, Nishioka homed in on the slopes of Mt. Maya in the Rokko mountains. He received assistance from Yozo Kudo, a former professor at Tokuyama National College of Technology and secretary-general of the Society for Recording Air Raids and War Damage.

Scanning the steep slopes with a metal detector, Nishioka unearthed eight fragments believed to have been remnants of the bomb dropped by the Enola Gay.

The first Pumpkin bomb raids from Tinian took place on July 20, 1945, just four days after the successful detonation of a nuclear test device at the Trinity site near Alamogordo, New Mexico.

Interestingly, even the bombs that missed their intended targets have been adopted into the pacifist narrative. On July 20 last year, citizens in Kitaibaragi City erected a memorial, 79 years to the day the first Pumpkin bomb was dropped. The B-29, named Top Secret, had been aiming at a military facility at nearby Otsu port, which was involved in the release of balloon bombs [see sidebar], thousands of which were released and carried by winds across the Pacific, aimed at North America.

The new memorial is situated several hundred meters from the hillside where the bomb actually impacted. Its inscription reads:

On July 20, 1945 (Showa 20), toward the end of World War 2, at 7:55 a.m., a mock atomic bomb (known by the US military as a Pumpkin bomb) exploded on a mountainside in the northeast of Isohara-cho, Kitaibaragi City. Latitude 36°48'54"N, longitude 140°44'40"E. It was a huge bomb using conventional explosives, the same shape and size as the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, measuring about 3.3 meters in length, 1.5 meters in diameter, and weighing about 5 tons. Since it missed its intended target, the center of Otsu-cho, by a large distance, no casualties occurred, but the explosion knocked down trees over an area of several dozen square meters, and gouging out a large crater of about 15 meters in diameter. The area where the bomb hit came to be called Bomb Mountain.

In 2018, Suzuki Katsutoshi, the sixth president of the Isohara Ujokai Association, revealed that the detonation on Bomb Mountain was the first training mission to have been carried out by the US atomic bombing forces. The horrific destruction wreaked by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki began here in Kitaibaragi City. We hope that people will not forget the mock atomic bombing in Kitaibaragi, feel the damage caused by the atomic bomb on their own, imagine the pain as if it were their own, and continue to strongly oppose the use of nuclear weapons. We dedicate this stone memorial, measuring about half the size of the actual bomb, keeping in mind the hopes of the local people for peace.

July 20, 2024

Composed by Noguchi Tomonori

Stonemason Kaminaga Mineyoshi

The memorial's reverse side carries a map of Japan listing the cities and dates where the Pumpkins fell, along with casualty figures.

Fourteen minutes after the detonation in Ibaragi, another Pumpkin bomb, dropped by the B-29 Straight Flush, exploded just northeast of Tokyo Central Station in the sotobori, the outer moat of the Imperial Palace, killing one person and injuring 62 others. Dropped using radar due to poor visibility, it was one of two Pumpkins that would fall on the Tokyo metropolis, the other detonating in Hoya (now Nishitokyo) City.

Between July 20 and August 14, 1945, 13 specially configured Silverplate B-29s of the 509th Composite Group flew a total of 49 practice missions, all but four of which attacked targets on Honshu. Broken down by prefecture, eight Pumpkins were dropped on Aichi, followed by Fukushima (five); Ehime, Hyogo, Niigata and Toyama (four); Yamaguchi, Mie and Shizuoka (three); and one or two on Kyoto, Gifu, Fukui, Mie, Shiga, Wakayama, Tokushima, Ibaragi and Tokyo. The deadliest of the 49 raids, carried out on July 29 by the Straight Flush on the naval arsenal in Maizuru City, Kyoto, killed 97 people and injured more than 100.

No aircraft were lost due to human or mechanical error or enemy fire. A possible disaster was averted, however, when a Pumpkin became unfastened in the bomb bay of the B-29 Strange Cargo while it was taxiing on the runway, falling through the closed bomb bay doors onto the taxiway and giving off a shower of sparks. Emergency crews doused the plane and bomb in protective foam, and the device failed to explode. The mission was scrubbed.

It seems gratuitous, but seven Pumpkin bombs were dropped on Aichi Prefecture on August 14 – the final day of the war. Four of these fell on the Nagoya Arsenal's Torimatsu factory and three on the Toyota factory in Koromo (renamed Toyota City in 1959), resulting in eight deaths and two injuries.

Soon after the war's end, the remaining 66 Pumpkins still on Tinian were loaded onto barges and dumped into the ocean.

On the final day of the war, four Pumpkins were dropped at the Nagoya Arsenal's Torimatsu factory, presently in Kasugai City, where this monument was erected.

This 121-page book by Hiroko Reijo introduces the story of the Pumpkin bombs to young Japanese readers.

In total, the approximately 400 deaths and 1,000 injuries resulting from Pumpkin bomb raids pale in comparison to the devastation and loss of life caused by the two atomic bombs. Yet new findings about how the Pumpkin missions were planned and implemented have added impetus to ongoing efforts by anti-nuclear organizations in Japan.

Aside from a classified report by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (The Effects of the Ten-thousand Pound Bombs on Japanese Targets: A report on nine incidents) issued in 1947, no English-language publication has been devoted specifically to the Pumpkin bombs, although several books and pamphlets have been published in Japanese. They include a remarkably complete study extracted from local research and declassified U.S. sources titled Genbaku Toka Butai: Dai 509 konsei gundan to genbaku/panpukin by Yozo Kudo and Tsutomu Kaneko (210 pages, privately published in 2013). Another is Pumpkin! Mogi Genbaku no Natsu, by Hiroko Reijo (Kodansha Aoitori Bunko, 121 pages, 2019). The latter is aimed at young readers.

Inflated expectations

Japan’s balloon bombs rode the Pacific winds to the U.S., but their impact was limited

When visiting the Pumpkin bomb memorial in Kitaibaragi, you might also want to take in two monuments to the so-called "balloon bombs” – the reason the area was targeted by the Americans. One is situated on the seacoast and another inland beside a local road from where the bombs were released.

In A Plague upon Humanity: The Secret Genocide of Axis Japan's Germ Warfare Operation (2004), Daniel Barenblatt describes the ingenious design of the balloon bombs:

Suspended from each balloon's equator was attached a ring of taut cords, bearing gondola-like carriages that contained incendiary bombs. An array of altimeters and gears on each balloon alternatively dropped sandbags to raise each balloon, or released hydrogen to lower it, to keep it at the right altitude for catching the westward jet stream, which could push the balloons along toward north America at speeds of up to sixty miles per hour. As a consequence, the journey from Japan to North America took no more than three days.

For those interested in learning more about the balloon bombs, the best place to go is the defunct Imperial Japanese Army Noborito Laboratory Museum for Education in Peace, located on the Ikuta Campus of Meiji University, which occupies a building that was once part of the Imperial Japanese Army's secret laboratory.

Along with a one-tenth scale model of these airborne weapons, visitors can see a granite washbasin, next to which is a wooden rack used to produce washi (fibrous handmade paper). In 1944 and 1945, hundreds of teenage girls with deft fingers labored here, constructing balloons from the paper and applying a protective coating of gelatinous konnyaku (an edible plant known as devil's tongue) to the exterior.

Meiji U. professor Akira Yamada explains the construction of balloon bombs to the author.

A memorial to six unnamed soldiers killed by accidental explosions of two balloon bombs.

In The Pacific War, 1931-1945: A Critical Perspective on Japan's Role in World War 2, historian Saburo Ienaga contrasted the resources of the two countries, writing: "While American scientists were splitting the atom, Japanese were engaged in windmills of quixotic futility."

Ironically, balloon bomb explosions appear to have caused the same number of fatalities in the U.S. and Japan: six. In Oregon, a monument was erected in the Mitchell Recreation Area in the Fremont National Forest, Lake County, in memory of six people (five of whom were children) who were killed when a balloon bomb exploded on May 5, 1945.

Unlike the U.S. tribute, the memorial in Japan does not carry the names of the victims. It reads: "On November 3, 1944, a balloon bomb was accidentally detonated due to a malfunction of the altitude positioning device during the early release, killing three soldiers. The names of the dead soldiers are not known because the balloon bomb project was treated as top secret.

“A similar accident occurred at Nakoso Base in Fukushima Prefecture, and this monument was erected by local volunteers to mourn the souls of the six Otsu-Nakoso victims.”

This year Mark Schreiber celebrates his 60th year in Asia. He is currently working on an essay about Japanese weekly magazines that will appear in an anthology about Japan's mass media.