Issue:

July 2025

The Japanese baseball world says farewell to Kyojin legend Shigeo Nagashima

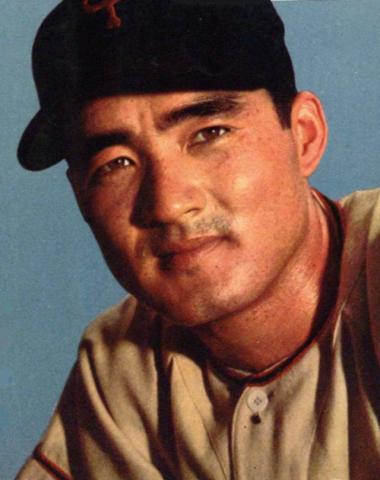

I read with sadness of the passing of Shigeo Nagashima, the former Yomiuri Giants star who died on June 3 aged 89. It is hard to put into words the effect that Nagashima had on Japan when he was an active player (1958-1974) and later as Kyojin manager. But it is accurate to say he was even more beloved than Shohei Ohtani, the Los Angeles Dodgers star with a ubiquitous presence today on billboards, subway posters and TV commercials in Japan.

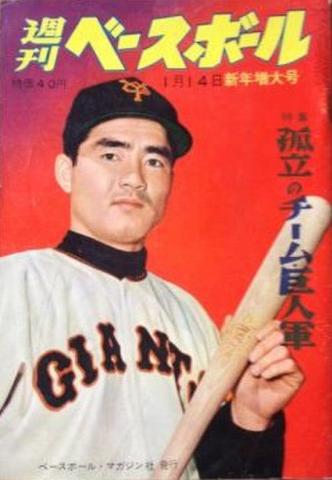

In The Chrysanthemum and the Bat, I wrote that Nagashima “was the most loved, most admired and most talked about figure in the history of sport since the days of Joe DiMaggio”. It seems like hyperbole in retrospect, but back then you couldn’t take a stroll along any Tokyo thoroughfare without seeing Nagashima’s face advertising some product or another: Toyota automobiles, Oronamin C health drink, Sanyo men’s clothing, Mitsubishi Bank, Hitachi and Sumitomo Life Insurance, among many others. He also appeared in several movies and TV dramas, and every single Giants’ game was televised to a nationwide audience of more than 20 million.

Nagashima graced the front pages of the sports dailies most days and appeared on the cover of the Shukan Bēsuboru (Weekly Baseball magazine) more times than any other baseball player in history. When he changed the kanji in his family name in 1965, it was headline news. When he married, his wedding ceremony was televised, and Gate 3 at Tokyo Dome is called the “Nagashima Gate” after his uniform number.

When I first came to Japan in the early 1960s, Nagashima was easily the most popular figure in the country — known nationwide as “Mister Giants.” He had been a college baseball star who joined Kyojin in 1958, and shot to eternal fame on June 25, 1959, when he hit two home runs, including a match-winning “sayonara” slog in the bottom of the ninth inning in the first (and only) Japanese professional baseball game Emperor Hirohito ever attended.

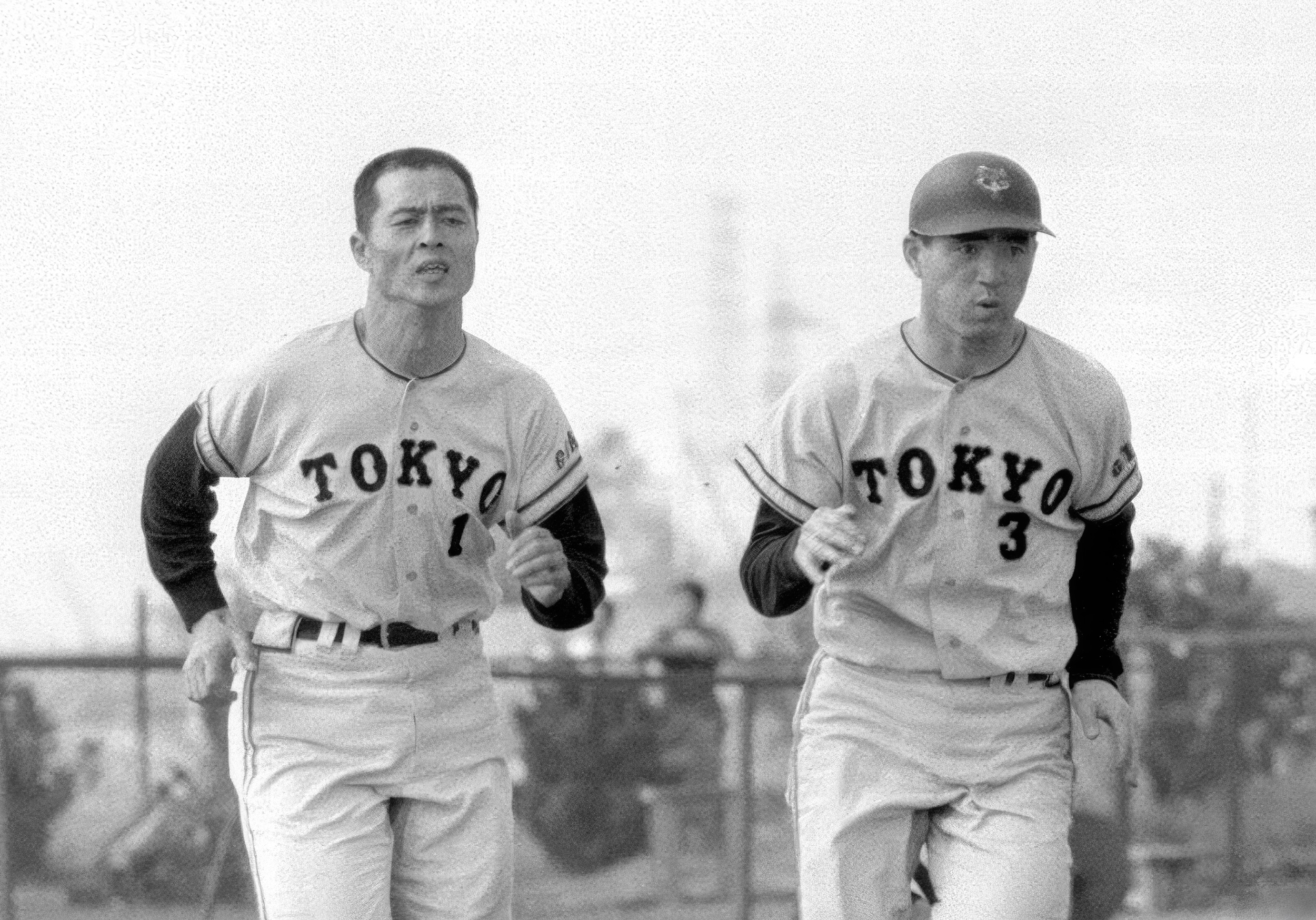

Nagashima combined with home run slugger Sadaharu Oh to form the famed “O-N Cannon”, which propelled the Giants to nine straight Japan championships between 1965 and 1973.

Nagashima won six batting titles in his 17-year career, finishing with 444 home runs and 1,522 RBI’s and a .919 slugging average. He won five MVP awards. He was chosen to the Best Nine All-Star Team every single season of his career. He compiled a stellar lifetime average of .305.

He had a flair for drama, often swinging so hard his batting helmet flew off. He had a well-deserved reputation for delivering in the clutch, helped in part by the fact that Oh, who had 868 homers in his career with multiple Triple Crowns, appeared ahead of him in the lineup, batting third to Nagashima’s cleanup and always seemingly standing on first base by virtue of a record number of walks. Nagashima had notoriously bad form, stepping in the bucket and hitting balls out of the strike zone for hits. Little League coaches advised their charges not to copy his swing.

He was also a dynamic, aggressive fielder who played so deep that he often intercepted ground balls heading straight for the shortstop. “Burning Man” was a popular nickname. So was “Imperial Man.”

He disliked talkative catchers and once directed a fart in the direction of Hanshin Tigers backstop Yasuhiko Tsuji to make him shut up.

Growing up he had idolized New York Yankees legend DiMaggio, and he was often called the “Joe DiMaggio of Japan” by admirers.

He was a mentor to Yankees star Hideki Matsui, who had played under Nagashima for the Giants. Matsui would frequently call Nagashima from New York when he was in a slump. Nagashima would have Matsui makes a few practice shadow swings near the receiver and reportedly could tell by the sound of the “whoosh” what Matsui was doing wrong.

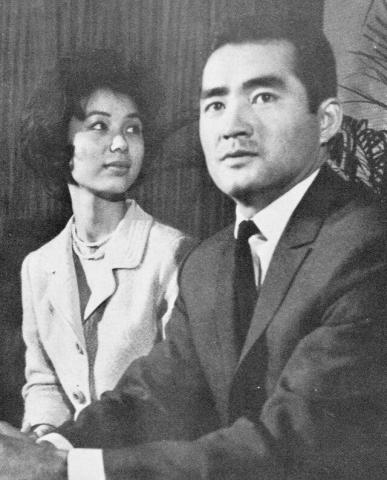

During the course of his playing career, Nagashima was routinely voted the most popular baseball player in the land in fan surveys, even though Oh had far better statistics. This was attributable perhaps to Nagashima’s movie star good looks and bright, bubbly personality, in stark contrast to Oh’s robotic, often glum demeanor. Others attributed it to the fact that Nagashima was a pure-blooded Japanese, whereas Oh, whose father was Chinese, was not.

Nagashima was, Japanese friends assured me, the closest thing to Japanese royalty. I saw evidence of this first hand when I went to his house in the Tokyo suburb of Denenchofu with a Canadian TV crew to film a visit by Montreal Expos star Gary Carter. Nagashima greeted us at the door, where a large photo of Nagashima shaking hands with then Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau was displayed. Carter, a Catholic, was ushered into living room and seated next to a table on which stood a photo of Nagashima with the Pope.

He took us to his basement where had a batting cage set up. All around the house were photographs of Nagashima with famous people: Ronald Reagan, Ken Takakura, Yujiro Ishihara, Tom Selleck, George W. Bush, Sophia Loren, Billy Martin, Giant Baba and Tom Cruise.

“Minna besuto furendo, Bob-san,” he said to me, gesturing to the pictures.

But of course.

He was notoriously absent minded, which the press delighted in reporting. In his rookie season he had what would have been his 30th home run taken away from him when he neglected to touch third base. As a less than successful Giants manager in later years over two different terms at the helm, he was often penalized for exceeding the allowed visits to the mound. He sometimes confused his players’ names, praising the wrong individual in postgame TV interviews.

Once he famously took his young son Kazushige, then in primary school, to Jingu Stadium and returned home without him, to the great chagrin of his wife Akiko. Kazushige later confided that it wasn’t the only time.

He was also famous for his fractured use of the Japanese and English languages. “Failure is success, mother,” was a favorite malapropism.

He once guest coached a baseball team in Australia sponsored by the Japanese company Akai Electric. Looking at the uniforms with Akai emblazoned on them he asked in all seriousness, “Why is everyone named Akai?”

Celebrating his 60th birthday he announced to assembled reporters, “This is the first time I turned 60.”

As a manager, he was an intense taskmaster, famously holding a postseason “hell camp” in Izu, after a disappointing finish. “Get the ambulances ready,” he ordered the Giants staff. Despite such training, he won just two pennants in 15 years as Kyojin manager.

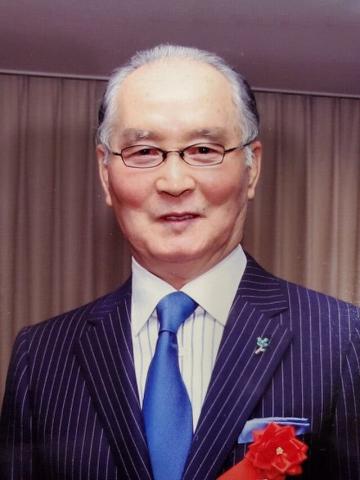

As he was preparing to manage the Japanese team at the Olympic Games in Athens in 2004, Nagashima, then 68, suffered a stroke that partially paralyzed the right side of his body. Despite the setback he continued to make public appearances and attend Giants games.

He died in a Tokyo hospital from the effects of pneumonia. He is survived by four children, including Kazushige, a former pro baseball player-turned TV celebrity.

His daughter, Mina, was a TV sports anchor, while another, Yuki, is an office executive. His second son, Masaoki, is a former racing car driver who became an environmental activist. Together, that have often been referred to as the “royal family” of baseball.

Ken Belson of the New York Times wrote in an obituary: “More than any player of his generation, Nagashima symbolized a country that was feverishly rebuilding after World War II and gaining clout as an economic power. Visiting dignitaries sought his company. His good looks and charisma helped make him an attraction; he was considered Japan’s most eligible bachelor until his wedding in 1965, which was broadcast nationally.”

Shigeo Nagashima, RIP.

Robert Whiting is a best-selling author and journalist who has written several successful books on sport and contemporary Japanese culture, including You Gotta Have Wa (1989), The Meaning of Ichiro (2004), Tokyo Junkie (2021) and Gamblers, Fraudsters, Dreamers & Spies: The Outsiders Who Shaped Modern Japan (2024).