Issue:

July 2025 | Ripping Yarns

A young reporter for a local newspaper in Britain suddenly finds himself a covering conflict in the jungles of Borneo

It was August 1966, and the weather was hot and steamy as I set out on my latest journalistic assignment. I had a notebook and pen in my pocket - routine for a reporter - and a rifle slung over my shoulder – not quite so routine. But this was no ordinary assignment: I was on patrol in the jungles of Sarawak, East Malaysia.

What on earth was a relatively young journalist, who only a week or so earlier had been reporting on municipal affairs for the Birmingham Post in Britain, doing in Sarawak – a state populated in those days by, among others, headhunting Dayaks – let alone carrying a lethal weapon?

I asked myself that question as I sweated and stumbled through the dense jungle, keeping a wary eye and ear open for enemy guerilla fighters and with my trigger finger at the ready. A sudden crashing sound nearby made me fear the worst. But it was only a startled wild pig.

To be honest, I felt less like an intrepid war correspondent and more like the hapless nature correspondent William Boot in Evelyn Waugh’s novel Scoop, who is mistaken by his editor for a staff war correspondent of the same name and dispatched to cover a military conflict somewhere in Africa.

My adventure began when the then editor of the Birmingham Post, David Hopkinson, called me into his office and told me that he had an assignment for me in “another place whose name begins with B”.

He said: “We want you to go to Borneo” for several weeks. I was somewhat taken aback. My knowledge of Borneo wasn’t great, but I knew about the headhunting tradition, which had been banned in the late 1800s but then resurfaced in the 1940s and surged briefly in the 1960s when the Indonesian government encouraged the Dayaks to purge the Chinese from interior Kalimantan.

Britain had at that time landed itself in a war with President Soekarno’s Indonesia, after amalgamating what was formerly known as British Borneo (Sarawak and Sabah) into Malaysia and calling it East Malaysia, even though Borneo was contiguous with Indonesia and 1,000 miles from the Malaysian mainland.

Soekarno responded by confronting Malaysia in a conflict known as Konfrontasi in Bahasa Indonesian. This was a war of attrition in which large numbers of British and Commonwealth troops had been killed or injured. It became known as the “forgotten war”, as the British public seemed neither to know or care much about it. Reporters, including me, were invited by the British Army (in my case, 42 Commando Royal Marines) to go and report on the conflict.

I flew from the UK to a staging-point in Singapore on a Bristol Britannia turboprop aircraft of somewhat ageing vintage equipped with canvas seats. The journey took more than 30 hours, including refuelling stops in Cyprus and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). It was not what you would call comfortable.

My companions were a reporter and a photographer from another UK paper. After we arrived in a still colonial-looking Singapore, we were taken by military Land Rover to the barracks of 42 Commando Royal Marines and assigned rooms in the Officers’ Quarters.

The first couple of days were not what I thought covering a war would be all about: a familiarization tour of Singapore, a few games of squash, liberal quantities of gin and tonic in the mess bar, and even a party attended by young women from the British Embassy and stewardesses – as they were known then – from the then British Overseas Airways Corporation. I began to think about enlisting in the Army, or at least of becoming a legitimate war correspondent.

We then travelled on to Borneo to the Sarawak capital of Kuching, again in a propeller aircraft whose pilot must have trained on aircraft carriers. The rate of descent to the airfield was so rapid – triggering intense pain in my eardrums – that upon landing I couldn’t make out more than a few words of the logistical briefing given by our commanding officer.

A long boat fitted with an outboard motor took us upriver to our jungle lodgings, which turned out to be a labyrinth of tunnels because, we were told, the “enemy” was occasionally lobbing mortar shells over the nearby border with Indonesia. Life underground, added to the steaming jungle heat, was so uncomfortable that I was almost relieved to be told on the second morning that I would be joining a patrol that day.

I was asked if I had handled a rifle before. Not really, I answered, thinking that I had come to cover a war rather than fight in one, to wield my pen rather than a sword. I was told that the “Indons” – meaning the Indonesian insurgents - were not obeying the Geneva Convention and shot at journalists from time to time. That meant I would be better off carrying a rifle while out on patrol.

I was handed a 36-round repeater rifle and targets were set up. After I surprised myself by hitting them, I was rewarded with a few hand grenades to chuck at metal objects that looked more like World

War II German panzer troops than enemy insurgents. That went quite well too, except that I almost dropped one in the trench where I was sheltering … after pulling out the pin.

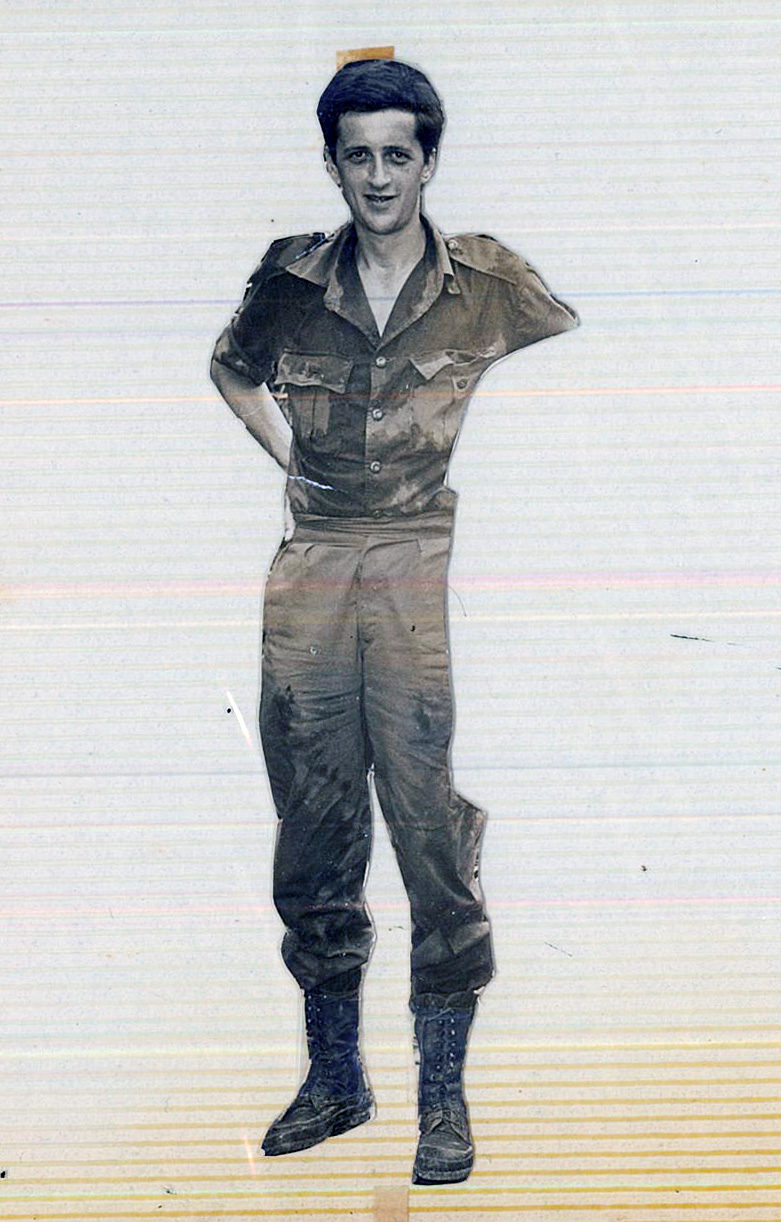

By this time I’d abandoned the blazer and flannels that I had packed in the UK in favour of military fatigues and boots. Off we went on patrol, led by a Dayak scout, each man told to maintain roughly a 40 yard gap between himself and the man in front. That way, if we came under fire, fewer were likely to be hit. No voice communication was allowed, only hand signals, and each man was told to look over his shoulder from time to time and check whether everything was okay behind him.

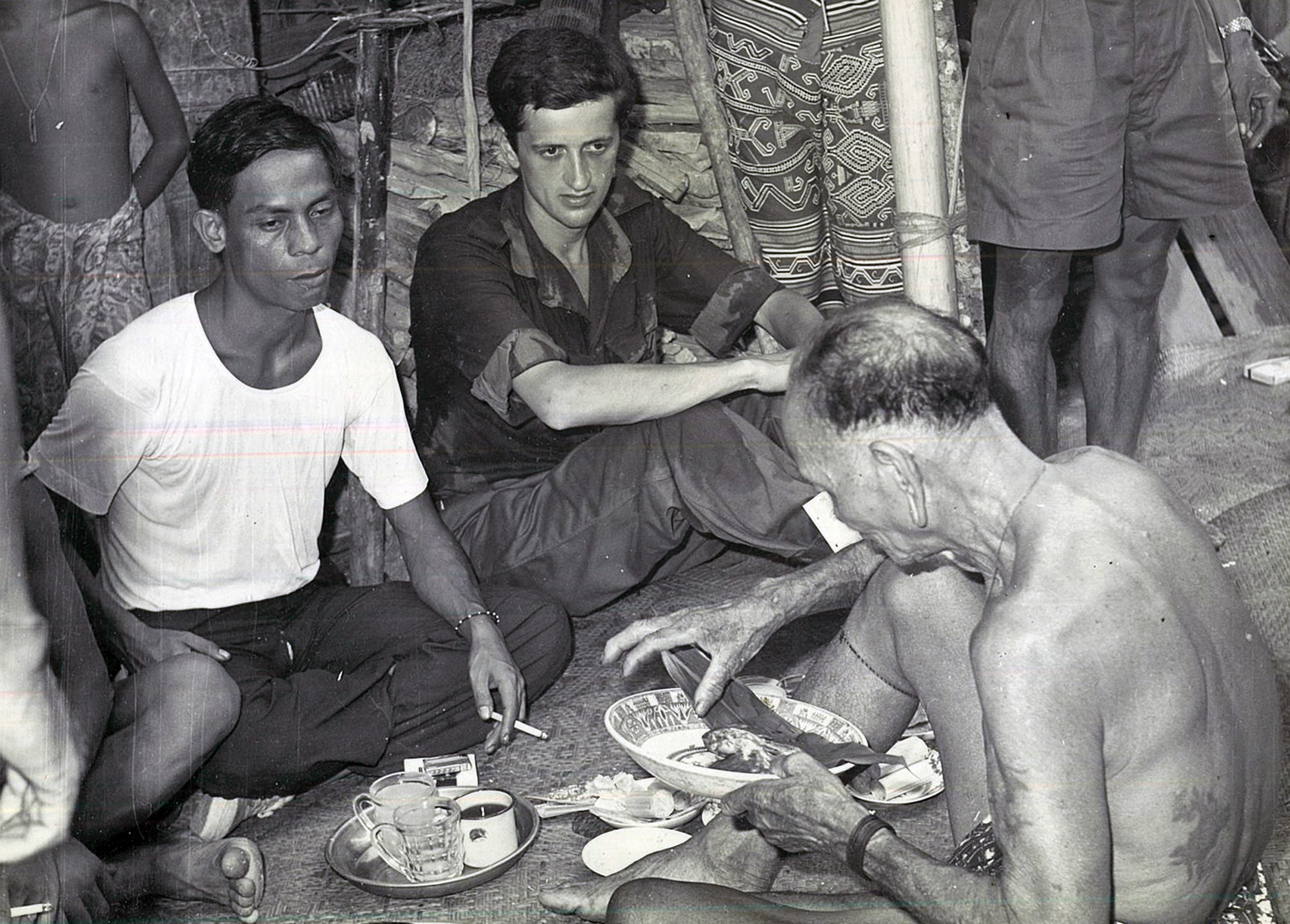

After what seemed an eternity trekking in the steaming heat, we arrived at a Dayak longhouse. Visiting these during patrols was part of the army’s “hearts and minds” campaign, the theory being that if you have to deal with headhunters, it’s wise to have them on your side than on the enemy’s.

These were the days before mass tourism, and the Dayaks lived in much the same way as they had for centuries. Each family occupied a room no bigger than a cell that fronted onto a long veranda in the raised wooden structure. There were nets outside each door, all containing collections of human skulls. It seemed impolitic to ask to whom they had belonged, but some looked white and relatively “fresh” compared with the more age-blackened ones.

It so happened that a grandson of the village chief was getting married, and we were invited to the festivities. These began with a cock fight in which the two combatant birds, metal spurs tied to their legs, went at each other with incredible ferocity, half-flying and squawking loudly. Each bout ended only when one of the birds had been reduced to a bloody and lifeless heap of feathers.

There was more to come. A piglet, squealing loudly, was brought out to the veranda-squatting chief, known as a pengarah, by two young men who proceeded to slit its throat and belly before extracting its liver and handing it to the pengarah on a tin plate. He moved his fingers slowly over the still-steaming organ to read the omens, and declared that his grandson's wife would bear many children.

After the wedding feast - rice cakes washed down with potent arak and tuak moonshine – our patrol lurched drunkenly back into the jungle. Marching through the jungle is the perfect hangover cure – you sweat so profusely that sobriety returns within minutes.

As we waded through muddy rivers, we were warned not to swallow the water as it was infested with leptospirosis organisms that could result in death within 24 hours. I kept my mouth firmly shut but was grimly amused to see Dayak kids swimming in the river and playfully blowing out fountains of water from their obviously immune open mouths.

Did I happen to have a dinner suit with me, I was asked in all seriousness the following day, as the regiment’s colonel was coming. As it happened, I did. White table cloths and even mess silver (I think) were laid out on long trestle tables in the jungle, and we ate with due ceremony, interrupted only by attacks from huge insects that looked and sounded like flying electric razors.

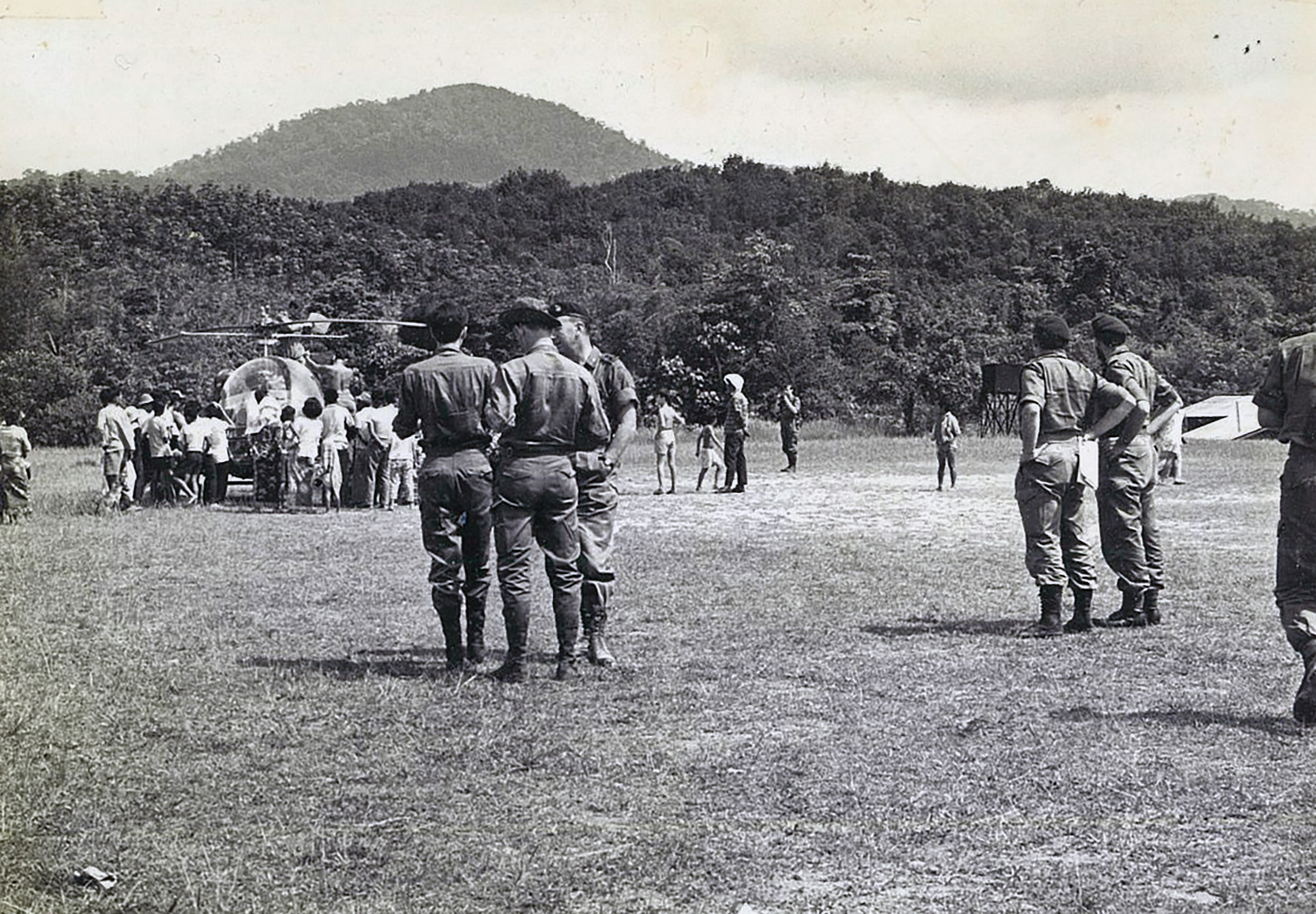

After Sarawak, we flew to Peninsular Malaysia to take part in a simulated assault landing on an east coast beach from the British aircraft carrier HMS Albion. The worst part of Exercise Long Hop was standing below deck in small groups in intense and oily heat, waiting to be airlifted by helicopter to the battle zone.

I came ashore feeling like one of the victors in the Battle of Dunkirk, except that the beach was deserted and there was no one to liberate. The “enemy” quickly emerged from the jungle, however, and sprayed us with blank rounds. I am happy to report that our side emerged victorious on points. The journalists were rewarded by being allowed to spend the night camping on the beach, swimming in the South China Sea and being cooked and catered for by army personnel. From there, the return journey was via Hong Kong, where the Mid-Levels addresses sought after by bankers and brokers today were almost entirely occupied by British Army barracks.

The Far East called again a decade or so later, after I had worked on the Times in London, first as a European business correspondent and then as a financial writer. I joined the Singapore Business Times as a founding writer in 1976 before moving to the Far Eastern Economic Review as business editor and then international finance editor.

What did I learn from my experience in the Borneo jungle? First, that journalism should be about exposing oneself to areas more exotic than politics and finance. A true journalist, as my one-time editor at the Times, William Rees-Mogg, once commented, should be able to write as fluently on spiritual or sporting affairs as on politics or economics.

In an age when journalism has gone the way of many other professions by producing limitless numbers of narrow specialists, this is still sound advice, even if I have perhaps allowed myself to be drawn into covering economic affairs more than is good for my journalistic soul.

Anthony Rowley is a columnist and contributor for the South China Morning Post.