Issue:

360⁰, 24/7

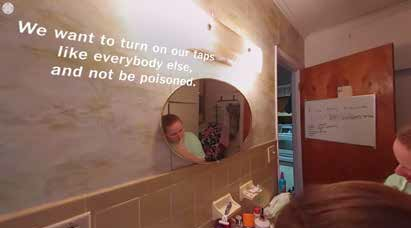

The New York Times’“Still Living with Bottled Water in Flint” (above) and “Fleeing Boko Haram and Food Shortages” (bottom right); Huffington Post VR stitcher Maria Fernanda Lauret at work (top right); Two screen grabs from the Japan Times’ look under the contaminated Toyoso market (right).

The news business is just beginning to react to new advances in 360° video and virtual reality.

From the development of the printing press, radio and television to the computer and mobile phone, technological advancement has often reshaped what it means to report the news. Each of these media has opened up new possibilities for mass communication as they have impacted the content and the very definition of the news itself.

An entirely new generation of media technologies is now clearly destined to reshape the news industry once again at a minimum adding new dimensions and new methods to journalists’ storytelling. At the head of the list are two quickly developing technologies 360° video and virtual reality, commonly known as VR.

The terms “360° video” and “VR” tend to be used interchangeably in many cases, but while they are, indeed, related concepts, there is an important distinction between them. As the name suggests, 360° video allows the viewer to observe a scene in all directions from the axis of the camera. This includes not only the entire horizontal view but up and down as well the full 360°.

Simple versions of 360° video are already available. YouTube began hosting 360° video in March 2015, and Facebook followed suit in September that year. Last April, YouTube became capable of live streaming such video, with Facebook again playing catch up in a December 2016 launch. Other platforms, such as Twitter and Periscope, are now in the process of joining them.

Presently on the YouTube and Facebook versions of 360° video, one can view a scene in any direction simply by clicking a mouse or using a trackpad. Yet this is neither very impressive nor how the technology is actually meant to be used. Rather, the genuine experience is to view 360° video while wearing a special headset, with the field of view changing as one turns one’s head. One is transported, so to speak, into a different world in which one’s eyes and mind are experiencing a remote scene.

THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN 360° video and VR is that, in the former, one may simply observe the scene in all directions, while in the latter, one may in some manner interact with and affect the remote scene which is being perceived. Today’s VR thus usually involves some form of animation. For all intents and purposes, 360° video may be considered a transitional technology, and is in fact sometimes referred to as “the gateway to VR.”

News organizations are already employing 360° video on their digital platforms. Internationally, the most aggressive pioneers are the New York Times and Huffington Post. The New York Times launched its full “Daily 360” series on Nov. 1, 2016, with a statement “that 360° videos offer a new way to experience the journalism of the New York Times. These immersive videos put you at the center of the scene.”

Marcelle Hopkins, the executive director for 360° video for the Times, says that “dozens of reporters” are currently using the special 360° video gear provided to them by Samsung. Many of the videos they produce are human interest stories, such as “Daybreak Around the World,” “52 Places to Go: Canada” and “Basking in Butterflies.” But their recent stories also include hardhitting reportage on subjects such as “Fleeing Boko Haram and Food Shortages,” “Sleeping on Denver’s Bitterly Cold Streets” and “Still Living with Bottled Water in Flint.”

“Part of the Times’ core mission is to bear witness to on the ground to events as they happen, in order to inform our readers,” says Hopkins. “We see powerful benefits to allowing the viewers to bear witness with us, whether it be a war zone or the site of a protest.”

AN EVEN EARLIER INNOVATOR was the news start up RYOT, launched in 2012 and later bought out and made a division of the Huffington Post in April 2016. By that time, they had already attracted considerable attention for presenting the first 360° news footage of the Nepal earthquake in May 2015 and of wartorn Aleppo in August that year.

RYOT was one of the very first to attempt to grapple with the special technical challenges of dealing with a technology in its infancy, in which entirely new problems crop up and workflows must be created from scratch. Overcoming these difficulties requires a new generation of skilled innovators like Maria Fernanda Lauret, a VR “stitcher” editor.

Most 360° video today is shot with multiple cameras simultaneously often five or six of them whose images must then be “stitched” together at the edges in order to create the illusion of a single scene occurring in all directions around the viewer. Lauret’s job is to make those stitches as seamless and unobtrusive as possible. “Depending on the distance between the Virtual Reality rig and the subject of your scene,” says Lauret, “the intersection of cameras is noticeable especially if there’s an object in motion around the camera. My job as a stitcher is to make these lines invisible for the viewers.”

REPORTING IN 360° ALSO has its own set of challenges, such as the location of the person shooting. The camera must be set up in the center of the action with the shooter then hiding somewhere out of view, controlling the recording by means of a remote device or become part of the shot. In the mean time, they must hope that a passerby doesn’t abscond with expensive camera gear, or simply accidentally knock over the rig while it is filming a dramatic news event.

Some basic 360° cameras have now become relatively inexpensive and are within easy reach of the journalist. The Ricoh Theta S is among the most popular and easy to use of these consumer level cameras, and this is precisely what the Japan Times has been using in its own initial experiments with 360° photography and video. (Development has been much more sluggish in the Japan based news media.)

“I had seen what the New York Times was doing,” says Mark Thompson, the deputy managing editor and senior web editor of the Japan Times. “I was more excited about the Virtual Reality stuff, and this seemed to be kind of a stepping stone to that. [We started] just to kind of get our feet wet.”

Thompson found a subject that was both newsworthy and ideal for the new media. “I saw the potential for news when we got invited to check out the basement of the new Toyosu market, the first time for the public to actually see the base ment,” he says, referring to the controversial move of the Tsukiji Fish Market, which has been delayed by Tokyo Gov. Yuriko Koike due to potential contamination issues. “We did a video of that and I thought that was a perfect application. You could see with your own eyes how high the water was in the basement.”

TRUE VIRTUAL REALITY IS a realm that journalism has yet to penetrate, but it is assuredly just around the corner. Despite many outstanding issues, its use will likely grow as the technology develops and the necessary equipment, such as Virtual Reality headsets, becomes standard household items.

Its main advantage will be allowing journalists to create “empathetic” responses to events and issues in the news more effectively than ever before. Viewers can be imaginatively transported to places or even to hold “face to face” meetings with other people that are in fact far away.

Though games on the Sony Playstation 4 are, like most video games, centered on action, such as gunfights, etc. there are a few, like Ocean Descent in which the viewer is slowly lowered down in a diving cage to view an undersea world that are more suggestive of the potential uses for journalism.

The gaming experience already demonstrates that VR can be very intense for participants. As Masaki Tsukakoshi of Sony’s Corporate Communications department says, “Many people using Virtual Reality can be seen to be physically reacting to the environment and scenes that they are experiencing within it.” Being surrounded by a frightening or dangerous environment such as war zones or disaster areas could be a traumatic experience for some viewers.

Along these lines, some of the pioneering uses of VR for journalism have been created by Nonny de la Peña, who has produced content taking participants to such places as the streets of Los Angeles as a man collapses due to hunger, or to Aleppo where children are playing when a rocket lands nearby. De la Peña describes her work as “immersive journalism” which conveys “the sights, sounds and feelings of news.”

But in its greatest strength also lies its most fundamental danger: The realities experienced within the headsets will be “virtual” realities, often designed to elicit certain responses. This means that concerns about “fake news” and public manipulation are likely to become even deeper and more complex in the coming era.

Indeed, commenting on YouTube to one of De la Peña’s presentations, journalist Heyley Longster wrote, “The only way to ‘accurately’ represent a scenario is to record events as they happen, and then play them back. Any element of ‘reconstruction’ by someone, journalist or no, involves an element of narration and projection that is extremely subjective. In other words, this isn’t journalism, it’s art.”

This is likely to become a recurring criticism of VR journalism in the years ahead.

Michael Penn is the President of the Shingetsu News Agency.