Issue:

In a small village in southern Japan, a dam project has been dividing the local community for over five decades. Most residents have left, but a few households continue the fight against the dam and they’ve been successful so far.

by SONJA BLASCHKE

On a Monday morning in June two years ago, a dozen women gathered in front of a construction site in Koharu Valley in Nagasaki Prefecture. The atmosphere was tense. They hid their faces behind scarves, masks and under wide brimmed hats with fly nets, and wore long, blue jackets from the local firefly festival to demonstrate their unity. They held signs reading: “We are against the dam” or “Stop forced expropriation.” They had been protesting there almost every single day for several months. What was at stake were their very homes.

Cars pulled up. Several men in work overalls, rubber boots and helmets got out and walked towards the small crowd, which huddled close together. Some of the men worked for a local construction firm, some were Nagasaki prefectural staff. For over 50 years now, the prefectural government has been trying to build a huge dam 234 meters wide and 55 meters tall. When completed, the Ishiki Dam would leave what is now the small Kobaru community submerged deep under countless cubic meters of lake water. Disappearing with the town would be its pristine natural surroundings, the habitat of several endemic species, say the protesters.

Yet, even after all this time, the dam is far from completion; even the foundations have yet to be laid. All that’s visible are a few barriers and some construction machines. The prefecture recently revised the completion date from March 2017 to March 2022.

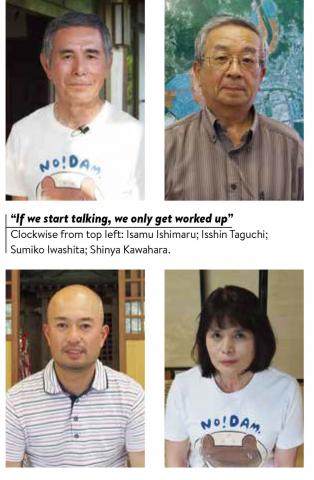

Though the officials and construction company managers kept appealing to the women to let the workers pass, the protesters remained silent. “If we start talking, we only get worked up,” Sumiko Iwashita explained later. The women felt that any discussion would lead to offers of compensation, but little in the way of a real exchange of opinions.

THE AUTHORITIES CONSIDER THE dam necessary to prevent flooding of the nearby Kawatana River and to supply water to the city of Sasebo, located about 40 minutes from Kobaru by car. Some decades ago, the city had experienced a water shortage and had to ration water for a while. However, Kobaru residents find reports about a supposed lack of water in Sase bo exaggerated. They argue that actual water use has been dropping with the introduction of new technology, and a predicted rise in population in Sasebo has failed to materialize. The dam opponents suspect some influence from Tokyo: the Liberal Democratic Party, which has dominated the country for decades, traditionally falls back on infrastructure projects to boost the economy.

Two years on, the protesters have refused to let themselves be intimidated. They are aware that once they give in, the 60 residents that remain in 13 of what were once close to 70 households will have to leave their hometown forever, there by abandoning land which, in some cases, their ancestors have inhabited for generations. Six days a week, from morning to evening, the women, flanked by non resident supporters, continue to block access to the site. Most of them are retirees. It once was the men, the household heads, who led the protest, but they were charged with obstruction of construction. If they actively take part in the protest, they can be fined, an activist explained. That was another reason why the women did not want to reveal their identity while protesting.

“There are not so many of us, so we cannot take turns. That is why we bring our lunches and some water, rain coats and umbrellas,” Iwashita explained. The youthful 66 year old is one of 60 people who after decades of fighting against the dam continue to live in Kobaru. With her husband and one of her sons she lives in a big house set a little above the fields. “I love nature,” she said with a smile. “Birds always sing here.” People who drive through Kobaru can see big signs reflecting the residents’ attitude on the roadside: “If your hometown was going to disappear how would you feel?”

OFFICIALS FROM NAGASAKI PREFECTURE insist they have done much to garner the understanding of the residents. In fact, construction work was paused for 30 years until, in 2009, the authorities decided to make use of the expropriation law, a highly unusual step. Generally, authorities try to “convince” people affected by a construction project, if necessary with pressure and money, as dam opponents believe.

The protesters took their case to court, but in December 2016 their suit to stop construction was dismissed. Only a few weeks later, on an early Sunday morning in January the only day of the week on which women did not gather workers brought heavy machinery to the construction site. Since then, confrontations along the site fence have been resumed with renewed vigour. At the same time, authorities have kept pushing expropriation efforts: for the past three years, a commission has been working on assessing the value of the remaining residents’ land to determine compensation payments.

Despite the image of the protesters as being of advanced age, there are also many young people living in Kobaru. One man, 43year old Shinya Kawahara, dressed in a striped T-shirt and beige pants, sat in the local community house, its walls decorated with black and white photos from protests, handwritten posters and banners from supporters from all over Japan. Born and raised in Kobaru, Kawahara, a shift worker at a local ceramic parts factory, said he could not imagine living else where. He loved playing with his teenage daughters at the river, observing fireflies in early summer, watching birds or collecting bugs. “This is the only home we have. I think it is natural for us to want to protect it.”

He was witness to an event that marked the beginning of this long running battle of wills. He was 11 in 1982, when he watched officials come to the valley to measure the land in preparation for the dam, accompanied by riot police. He saw policemen lifting grandmothers who were sitting on the ground and hauling them away. Crying children were carried off or thrown to the side, he remembered. Kawahara himself tried to punch a policeman in the stomach, but the man was wearing a metal plate under his shirt.

THE REMAINING RESIDENTS POINT to the brutal police operation in 1982 as the reason they lost trust in the prefectural administration. In fact, the authority itself acknowledges that the incident inflicted “deep wounds to the hearts of the residents,” and the governor at the time attempted to make amends by sending apology letters and trying to meet with Kobaru residents.

However, four kanji 面会拒否 on a sign at the door of 66 year old Isamu Ishimaru’s house are a token of the failure of those attempts of reconciliation. They read menkai kyohi or “refusal to meet,” and they refer to his deep disappointment in politicians, including the former governor, who broke his promise not to build the dam if just one person was against it.

Although Ishimaru only arrived in 1978 from the nearby Amakusa islands with his parents, he considers the little Kobaru Valley home. “This is where traditional Japanese society still remains intact,” he said. Ishimaru walked slowly on a small road leading up to his house where he lives with his wife and daughter, gazing across the light green rice fields. Dragonflies were flitting through the air. Between the rice plants one could hear frogs croak.

Ishimaru talked about his defiance while pointing to a small street skirting some of his rice fields. That would be where the new main road would to go through, he explained, as the current one would be submerged. Some of his fields were already expropriated on paper, but he continued to plant rice on them anyway. The former public servant considers the expropriation a violation of the Japanese Constitution, which guarantees the right to life, freedom and pursuit of happiness.

But there are those who have accepted the government’s plans and moved out. Over the past decades, more than 50 households have given up and left. A new housing estate for those who left the valley stands in nearby Kawatana, the village of 14,000 people of which Kobaru is a part. Although it’s only a few kilometers down the road, the emotional distance is enormous; the people who moved here from Kobaru, especially the elderly generation in their sixties, do not speak with their former neighbors anymore. Both sides feel betrayed.

While there is some support from outside the valley, it seems that most of their immediate neighbors do not feel like getting involved in the struggle. The family of Isshin Taguchi has been living in Kawatana village, downstream from the dam and therefore unaffected by the project, for over a hundred years. In fact, the unaffiliated, conservative local politician and former ministerial bureaucrat who heads up the dam construction committee argues that the dam is important as a measure to prevent floods. In the nineties, part of Kawatana was severely damaged by flooding after strong rainfall. “I am not exactly eager for the dam to be built but it is just necessary,” he says. Nagasaki Prefecture emphasizes that the Ishiki Dam would protect the area from severe floods that occur with a statistical frequency of once in a hundred years.

Despite all of the setbacks the Kobaru residents try to stay positive. What encourages them is that the authorities still have not managed to move the project visibly forward. In fact, there are many major construction projects throughout the country, from dams to nuclear power plants, which have been stalled or prevented by local resistance. There was also the local resistance to the Arase Dam in Kumamoto Prefecture that led to its being completely torn down, in the only such case in Japan. Thanks to young, dedicated residents like Shinya Kawahara, who feel called to continue the protest, there seems to be little chance of the resistance in Kobaru fading.

At the protest site, the soft spoken yet feisty Iwashita revealed how she managed to keep her balance and persevere through the exhausting fight: She did not think ahead much, she said. To relax she likes to rip out weeds in her garden. She emphasized that the women tried to keep up their good spirits by enjoying delicious food and by laughing together a lot, “because you cannot fight if you are depressed.”

Kawahara, the local born ceramic maker employee, said he suppressed thoughts about the fact that he might have to move away some day. “I will get old in Kobaru,” he stated decisively.

Sonja Blaschke is a freelance East Asia and Australasia correspondent for German print media and a TV producer. She divides her time between Japan and Australia.