Issue:

Remembering a difficult birth

A tough, post war battle over censorship between correspondents and the Occupation authorities led to the formation of one of the world’s great press organizations.

by EIICHIRO TOKUMOTO

At 8:50 a.m. on Sept. 2, 1945, under gray, overhanging clouds, a U.S. navy launch made its way across the waters of Tokyo Bay. Its passengers a party of 11 men making up the Japanese delegation to the surrender ceremony wore anxious expressions as they pulled up alongside the U.S.S. Missouri. Headed by Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, the group was met on the deck by awaiting representatives of the U.S., Great Britain, the Soviet Union, China and other Allied nations. As a multitude of American sailors looked on quietly, General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, began his speech.

“We are gathered here, representatives of the major warring powers, to conclude a solemn agreement whereby peace may be restored. . . . It is my earnest hope, and indeed the hope of all mankind, that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past. . . .”

Shigemitsu and a senior member of the Japanese military affixed their signatures to the surrender document, followed by various national representatives. After six years almost to the day, the Second World War was brought to an end.

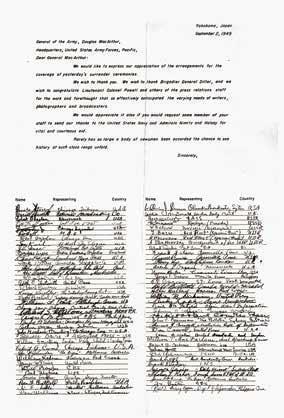

On Sept. 3, the day after the ceremony, General MacArthur received a letter of thanks, signed by 76 correspondents from the Associated Press, CBS, the BBC, Reuters, the Soviet news agency TASS and others. This letter is now in the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University in California.

“Dear General MacArthur,” the letter read. “We would like to express our appreciation of the arrangements for the coverage of yesterday’s surrender ceremonies. We wish to thank you. We wish to thank Brigadier General Diller, and we wish to congratulate Lieutenant Colonel Powell and others of the press relations staff for the work and forethought that so effectively anticipated the varying needs of writers, photographers and broadcasters. . . . Rarely has so large a body of newsmen been accorded the chance to see history at such close range unfold.”

The letter clearly conveyed the enthusiasm of having witnessed an historical event, but ironically it was this letter that was a critical shot in an ongoing battle between MacArthur and correspondents, as well as being a catalyst in the creation of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan.

As the head of GHQ, MacArthur forcefully proceeded with the demilitarization and democratization of Japan. His aim was to reform the political system, including the constitution, as well as the economic and education systems. But throughout the general’s military campaign in the Pacific, he had strictly controlled press reports, and if the reporters expected MacArthur’s staff to change their ways, they soon learned otherwise.

THE HEADQUARTERS WAS QUICK to censor any negative media reportage of Occupation policies, and Occupation authorities saw strict regulation of the press as part of the job. One reporter who personally experienced this was Keyes Beech, correspondent for the Chicago Daily News (and also president of the FCCJ from July 1948 to June 1949).

In his memoir, Tokyo and Points East, Beech wrote that in the beginning GHQ accorded journalists the same treatment as high ranking military officers, providing them with lavish homes with servants. At that time, Japan was described as “the only place where a reporter can live like a publisher.” But Beech also found disadvantages to such deferential treatment, “an invisible price tag on this luxury.”

“It was never mentioned, but it was always there,” he wrote. “The price was conformity to the MacArthur doctrine that everything in Japan was perfect . . . the point was that if you accepted these things from MacArthur the Good Provider and you had no alternative but to accept them if you wish to remain in Japan you were not supposed to criticize. That was almost literally biting the hand that was feeding you . . . . Correspondents were supposed to be content with the handouts. Questions that went beyond the handouts were unfriendly.”

One day, Beech approached Major General Hugh Casey, MacArthur’s chief engineer, and asked him how much the Occupation was costing both American and Japanese taxpayers. When pressed for details, Casey replied in an irritated tone, “I don’t think the people of Chicago are interested in such details.”

Beech wasn’t about to let it go. “I replied with equal irritation that I did not propose to tell Casey how to build a bridge and that I did not want him to tell me what might be of interest to the people of Chicago. . . . from this and similar experiences during four years of life under MacArthur I learned to dislike dictatorships, no matter how benevolent. And MacArthur was a very benevolent man.”

But reporters like Beech were in the minority; most were content to follow the GHQ line.

“. . . most correspondents in Tokyo and I refer specifically to the major news agencies dutifully fed the MacArthur line to American readers word for word, even though they often knew that what they were sending was not the truth or at least not the whole truth. Their justification was objectivity. In short, MacArthur had said it, and even if what he said was an outright lie it was not their responsibility to contradict him.”

BUT WHEN CENSORSHIP RULES stayed draconian despite the war’s end, protests eventually began to gather steam. And what eventually sparked a revolution was the Oct. 12, 1945 announcement that a “quota system” would be put into effect, with the aim of reducing the number of foreign correspondents. The various news bureaus were assigned a quota for the number of reporters they could bring in, and the correspondents were reverted to civilian status, effectively giving GHQ control over their food, housing and transportation. The person who put the new system into practice was none other than the same Brigadier General LeGrande A. Diller who the correspondents had mentioned in their thank you letter following the surrender ceremony. Soon they began to refer to the high ranking officer with the less flattering nickname of “Killer” Diller.

According to former United Press correspondent William J. Coughlin’s book, Conquered Press, Gen. Diller threatened the reporters: “We are getting tough. And we are going to get tougher. We are not going to let you give MacArthur’s critics in the States any ammunition. . . . Don’t forget the Army controls the food here.”

That was the final straw. The infuriated reporters met in a conference room at the Radio Tokyo building to discuss ways they could defy the military’s efforts to stifle their reporting. They decided, wrote the New York Herald Tribune’s Frank Kelley and the London Daily Telegraph’s Cornelius Ryan in their book, Star Spangled Mikado, “to officially notify the Supreme Commander that the association would set up its own press hostel and provide accommodation, no matter how bad, for all correspondents ‘what ever his creed, race or color,’ arriving in Japan.”

They arranged to rent the Marunouchi Kaikan, a five story building in the Marunouchi district, from its owner Mitsubishi. In October 1945, the Tokyo Correspondents’ Club, the forerunner of the FCCJ, was founded. It consisted of a dining room and bar on the ground floor nicknamed No. 1 Shimbun Alley and upstairs, a room for press conferences as well as sleeping facilities. When the Club opened for business in November, the membership was approximately 170 reporters.

Australian correspondent Richard Hughes agreed to work as the General Manager for a salary of $80 a week plus free board and half price on drinks. In those days, the club was a place where foreigners and Japanese were free to come and go. In his personal memoir, titled Foreign Devil, Hughes described the club as “the liveliest and least conventional residential club in the world” and “makeshift bordello, inefficient gaming house and blackmarket centre.”

Wrote Hughes: “We had a mixed membership of war weary correspondents, the world’s best reporters and combat photographers, liberal, conservative and radical commentators, and some of the world’s most plausible rogues and magisterial scoundrels. . . . No one can pretend to be uninformed in a press club. News and revelation, scandal and fact bizarre and blue bolted are always on tap at the bar at first or second hand.”

According to Hughes, the most popular bedroom among correspondents was Room 7 on the fourth floor. “I have a waiting list of seven residents who wish to transfer to Room 7. . . . This popular room overlooks the large windows of the showers and two bedrooms in the Soviet women’s billet next door. The Russian girls seldom draw the blinds.

IT WAS NOT ONLY GHQ that attempted to influence stories by press club members. In January 1949, the Times correspondent Frank Hawley covered the political situation following Japan’s general election. On Feb. 26, British political representative in Japan Sir Alvary Gascoigne received a letter from Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida via Yoshida’s secretary. According to declassified documents of the British Foreign Office at the National Archives in London, the letter contained a protest over Hawley’s article.

“I learned to dislike dictatorships, no matter how benevolent. And MacArthur was a very benevolent man.”

“My attention has been called to certain recent articles in the Times, in which I and my party are represented as being ‘opposed to the Allied Headquarters policy’ and harboring a ‘dislike of the ideals of Anglo Saxon democracy’ . . . . I regret that such absurd, malicious and grossly distorted notions about my party, which are circulated for propaganda by our political enemy, should have been swallowed by the Times correspondent here, and accepted by Times editors in London.”

In his own report to the Foreign Office in London, Gascoigne showed a deep understanding of the role of the press and how to deal with them. “I am not, of course, replying to this letter on paper,” he wrote. “I have simply told Yoshida’s Private Secretary to remind his chief that the press in the United Kingdom is entirely free and that what is written in the Times is not necessarily connected in any way with the trend of official thought held in London. . . . I mean to show Yoshida’s letter to Frank Hawley, the local Times representative, next time he comes to see me. But I shall do so of course in jocular fashion and with no show of attempting to influence him one way or the other.”

Recently the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in particular, have shown dissatisfaction over articles written by foreign correspondents, and been criticized for their attempts to intervene on the articles’ contents. But perhaps it’s a bit unfair to single out PM Abe for such efforts. Since its founding in 1945, the FCCJ has always been something of a gadfly toward the powers that be, including GHQ.

Arising from the ruins of Tokyo 70 years ago this month, the Tokyo Correspondents Club and the subsequent Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan has been the home away from home for legions of distinguished journalists, spawning many dramas and legends. Along with the stories they filed, the old black and white photos adorn the club’s lobby as a testament to their presence.

Eiichiro Tokumoto, a former Reuters correspondent, is an author and investigative journalist.