Issue:

“Newspapers must not be run behind closed doors. They must face the masses, and must have the general orientation and at the same time be fresh and lively”

– editor John Roderick quotes Mao Tse-tung, first edition of No. 1 Shimbun, Sept. 1968

Press clubs, pros and cons

Kisha (press) clubs, not the sources or the media, determine who covers the news, what questions are asked in many cases, what information is released to the public and generally, how news media conduct their news- gathering operations. The press clubs are able to enforce their will because the sources cooperate with them and do not violate rules the clubs set down. Some officials and politicians complain privately that unless they go along with the clubs they will be attacked publicly. In reality, the clubs are so close to their sources that most of what is printed is just what the sources want printed.

– Richard “Dick” Halloran,

Vol. 1 No. 4, Dec. 1968

Why No. 1 Shimbun?

In the days immediately after World War II, most of Tokyo lay in ruins. Street addresses – in a country which never had them anyway – were a problem. What was to be the address of the newly established Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan? One of the many geniuses in our membership back then hit upon the happy solution, “No. 1 Shimbun Alley.” Despite three moves, the post office continues to deliver mail and telegrams to us promptly if it carries that address.

Since shimbun, as anyone here for 15 minutes could tell you, means “newspaper,” what better name for our paper than No. 1 Shimbun?

– No. 1 Shimbun, Vol. 1 No. 1, Sept. 1968

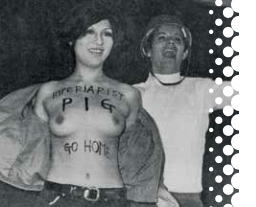

“Femen” ja nai

A news skit at the Club’s 23rd anniversary party – perhaps the only time topless women in the Club’s early days actually carried a message.

Vol. 1 No. 4 Dec. 1968

Two hours with a Nobel Laureate

Yasunari Kawabata is known for being taciturn. At first, one is struck by his apprehensiveness, which, for an interviewer, would seem to foreshadow a difficult and evasive conversation. Yet after an exhaustive day, disrupted by friends and run of the mill interviews with dozens of Japanese journalists, he willingly saw me for an interview which was to last a quarter of an hour and, at the most, a half hour. It lasted two hours.

Mr. Kawabata said: “I considered for a moment refusing the Nobel Prize because I was judged on translations, which are excellent by the way . . . and though the Nobel Prize is a very great honor for an author, an honor to which I had aspired without believing I would achieve it, it is also, perhaps, a very heavy burden.

“But through me, I felt that the Nobel Academy wanted to render homage to our tradition, to the Japanese sense of beauty, and especially to honor all Japanese literature. Until now, it hasn’t been appreciated abroad, but perhaps, at last, it may shine thoughout the entire world.

“I feel nevertheless that I owe a great deal to my translators; also to Yukio Mishima, who didn’t receive the Nobel Prize last year because of his youth, but who has drawn attention to Japanese literature. It’s a pity . . . he’ll have to wait longer.

lish death. But death here doesn’t have the same meaning as in Christian Europe. The Japanese tradition isn’t immoral. It’s amoral. It is synonymous with nothingness.

“The Japanese whose culture has been shaped by Zen are particularly absorbed by the idea of nothingness, or rather by its contemplation. It is comparable to Western nihilism, but there is a great difference between the two conceptions. In the East, nihilism is a type of philosophy which seeks harmony between man, nature and nothingness.”

Kawabata regards affectionately a figurine in Haniwa earthenware on a lacquered table and points it out to me. It dates from the Fourth Century after Jesus Christ and he emphasizes that it is purely Japanese, preceding by two centuries the appearance of Chinese civilization on the Japanese archipelago.

He admires its simplicity and at the same time its great warmth. The hollow openings that form the eyes and mouth invite the eye to plunge into the interior, into the emptiness and obscurity, into nothingness.

“All my life is a search for beauty and I will continue searching for it to the moment of my death.”

– Jean-Francois Delassus, Vol. 1 No. 3, Nov. 1968

To the Moon and back

Vol. 2 No. 8,

Members and their guests were glued to the television sets (20 of them, all color, provided by Toshiba and Sony) in the main bar, stag bar, dining room and corridors as moon man Neil Armstrong put down the earth’s most celebrated foot on the lunar surface. Others clustered around teletypes in the library to read the running accounts by AP, Reuters and UPI.

Aug. 1969

Honda has no fears

What new developments are on the drawing board in [Honda founder] Soichiro Honda’s lab? “That’s a secret,” says Honda. . . . I asked whether a completely automated brake is still a pipe dream for now. “Why?” asks Honda. “You can’t say it’s impossible.” Then he goes on about an electronic beam, a sort of radar system that not only would sound the alarm when a vehicle approaches, but would make the necessary corrections in the car. “That at least would be one situation the driver wouldn’t have to worry about,” he remarked.

– Thomas Ross,

Vol. 2 No. 1, Jan. 1969