Issue:

An experienced journalist/editor shares tips on writing an investigative report that will have an impact on readers

GREAT INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING OFTEN turns into difficult, hard to read articles. At best, these stories are boring; at worst, they are impossible to understand. Sadly, they end up having little or no impact, meaning months of difficult investigative work has been largely wasted.

It’s not difficult to work out whether your story is understandable or not: if your grandmother can’t grasp it, you have failed. And complex subject matter is no excuse. While writers like to blame readers for not understanding or caring about their work, lack of clarity is always the writer’s (and their editor’s) fault. One of the keys to good journalism is to make the important interesting, and the solution is better storytelling. You must tell stories in a way that helps impose order on messy realities and inspires empathy in your readers.

At this summer’s annual investigative journalism festival in Kiev, Ilya Lozovsky, managing editor of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, shared some tips to help investigative journalists do just that. Here are his top 12 tips on how to craft a compelling story:

1. Explain your story in one sentence.

You have to figure out what your story is before you start writing. Can you convey its essence in a tweet? If not, you probably aren’t ready to write. You might need additional reporting. Work backward in time. Ask yourself: What caused the event you are reporting on to happen? What were the factors in the environment legislative, social, political that made the event possible? Who and how were the key people involved?

2. Select facts that matter.

You have probably uncovered thousands of facts in your research. But you can’t throw them all at the reader, and expect them to absorb them all. When we tell our friends something that happened to us, we don’t just recite every single fact. We pick the most relevant ones, tell them in order and explain what they mean. One of the most important parts of storytelling is being selective each fact needs to be there for a reason, and you have to explain that reason to your audience. It’s not a failure to use only 5 percent of what you found.

Remember to always think from the perspective of the reader: Is this sentence helping them better understand the story? Does it advance the story? Also, try limiting names and numbers to no more than two per paragraph so you don’t bog down or confuse your reader.

“Remember to always think from the perspective of the reader: Is this sentence helping them better understand the story?”

3. Choose the sequence of your reporting.

A story is a highly selective sequence of relevant events that have significance for your reader; all stories should have a clear beginning, middle and an end.

If you’re lucky, your story will be obvious. It will feel like it is writing itself. But most of the time, it’s not that simple. You have a whole lot of facts, but facts themselves do not make a story and if you write that way, you’ll just end up with a list of facts that most people will never read.

Chronological order is almost always the best way to tell a complex investigative story. Some stories may be told in other ways, but only in special circumstances.

4. Give readers a reason to empathize.

Readers need to understand why they should care. Sometimes your story will have obvious victims, but many times it won’t. You need to explain who has been hurt and how.

In investigative reporting, it’s often the citizens or the country’s budget which are the victims. But it can be more nebulous. Is it your country’s reputation? Democratic norms and institutions? Societal trust?

When it is money that is lost or stolen, you’ll need to explain what that amount means. Your grandmother doesn’t know how much a billion is, because she has never seen that much money. You need to explain it in a way she’ll understand. How many hospitals can be built with that amount of money? Can you compare the amount to the average annual salary of a teacher?

5. Highlight and introduce characters.

Characters don’t have to be people places or things can be characters, too! but they usually are people in investigative reporting. Remember, every character mentioned must be introduced, and their motivations and involvement in the story has to be explained.

Who are they? And why are they in the story?

Be sure to write “there he met James Smith, a banker from New York,” and not just, “there he met James Smith.”

6. Show us the map first, then take us on the journey.

Signposts signal where the story will go. Here’s how a typical story can be set up:

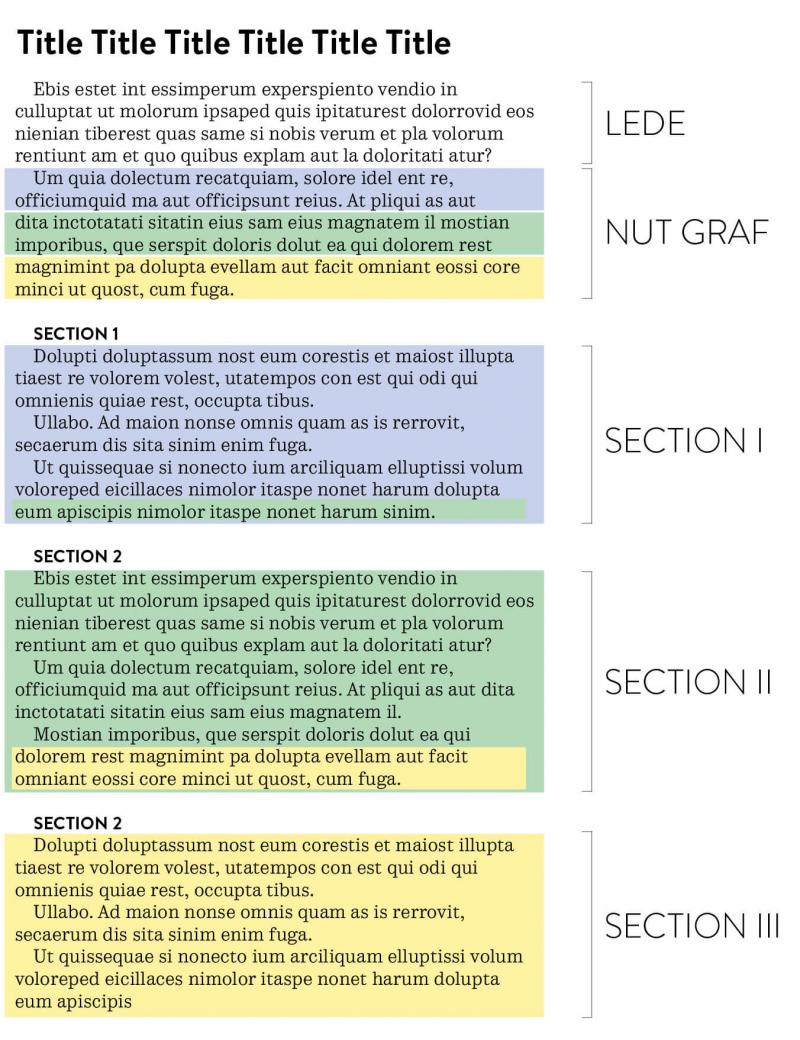

- The “lede” is what sets up the story and takes the reader in.

- The “nut graf” shows the reader where you’re going. This is where you tell the reader what you’re going to tell them; your single sentence that explains your story comes in handy here. The lede and the nut graph make up the beginning of your story.

- The body of the piece the middle is where you explain your story. This is usually broken up into several sections where you make your key points and outline the facts that back up your nut graph.

- In your ending, you tell them what you just told them, summing it all up.

7. No surprises!

Some journalists like to “reveal” surprises in the second half of the story. This violates the rule of “guiding the reader.” Assume most readers won’t get there!

When new elements are introduced, their connection to previous elements should be clear. Is it the same criminal case or a different one? If you have written “charged three times with bribery” at the beginning of the story and you mention “arrested for bribery” again later, make it clear whether it’s one of the three.

8. Color your story.

Show how something looked. Show how someone acted. Write about smells, colors and sounds. Make people and places come alive. While this may appear to violate the rule about “no extra details,” these are, in fact, serving a purpose. Storytelling is nothing without story.

9. Involve an expert.

Get independent specialists to offer comments on the subject of your story. It can assist with explaining the complex; oftentimes experts can say things you can’t. For example, after describing a complex set of transactions, it’s great to have a specialist say: “This is obviously a bribe,” especially if they can explain why.

10. Use simple language.

- Go for concrete language over abstract.

- Avoid jargon.

- Active voice is better than passive voice.

- Use lots of verbs and nouns, and less adjectives. Avoid adverbs!

- Variation: Mix long sentences with short ones.

11. Be creative with supplementing the text in order to avoid interrupting the narrative.

- Charts and graphs

- Infographics

- Boxes

- Sidebars

12. Don’t pay too much attention to the end of your story.

How do you end a story? The truth is, it doesn’t matter as much as you think it does. On longer reads, most people won’t read to the end; 80 percent of your writing effort should go towards the top 20 percent of the story. Really. As an editor, if I had a bad draft and only an hour before publication, I would just focus on the lede and nut graf.

And here’s some bonus tips from an editor’s perspective:

- Take a break before sitting down to write. Always write with fresh eyes.

- “Write drunk. Edit sober.”

- Read out loud do you stumble over anything? Fix those awkward places.

- Editors are your friends. They will see things you won’t.

Olga Simanovych is the Russian language editor of the Global Investigative Journalism Network. She has worked as a screenwriter, media trainer, managing editor, TV news reporter for Vikna Novyny and has participated in international investigations. This article originally appeared on the GIJN website and is used with permission.