Issue:

A year after changing owners, the Japan Times finds itself embroiled in a fight over the past.

Press freedom in Japan has been the focus of growing debate in recent years amid reports of pressure on reporters to toe the line of the Abe administration. The latest episode in this saga was a change in editorial policy on WWII related terms at the Japan Times, under new management since 2017, that sparked heated debate in the newsroom and threats of cancellations from irate subscribers.

It began with a Friday, Nov. 30 page two “Editor’s note,” appended to a story on a judgment by South Korea’s Supreme Court against Mitsubishi Heavy Industries for its use of Korean workers. The paper mentioned it was changing nomenclature when referring to comfort women and forced laborers to “women who worked in wartime brothels, including those who did so against their will, to provide sex to Japanese soldiers” and “wartime laborers.” Many readers, including your humble scribe (disclosure: I am also a contributor to the Japan Times), were surprised.

The reaction from readers of the paper was swift. In a blog entry later that day, Minako Kambara Suematsu, CEO of the JT’s owner News2U Holdings, wrote of her astonishment at the intense response from readers on social media and in phone calls. She said the change in wording was the result of long discussions among the editors with diverse opinions, and expressed support for the editorial department. She closed with the vague promise that “The Japan Times will continue to correctly communicate the present and future of Japan to the world.”

MEANWHILE, THE MOVE BY the paper was generating international headlines and an internal revolt. Over the weekend, the Guardian, NPR and the Chosun Ilbo, among others, ran stories on the change in wording, reporting critics’ views that the paper had bowed to rightwing pressure to change historical descriptions. The New York Times, whose international edition is distributed by the Japan Times, appeared to have been blindsided by the paper’s move. Danielle Rhoades Ha, NYT VP Communications, told the Number 1 Shimbun: “The New York Times uses precise language on this topic and will continue to do so.”

As discontent among staff members continued to simmer, the paper had to act. On Monday, Dec. 3, Executive Editor Hiroyasu Mizuno met with the staff over two hours in an attempt to calm the waters. He and CEO Suematsu followed up with another marathon session the next day, in which many reporters and editors expressed their views. In the end, a compromise was reached: a new committee would be formed and assigned to review the matter of the controversial wording.

On Dec. 6, an extraordinary message signed by Mizuno was splashed over one full page in the paper. Titled “We are listening,” it was a statement in which he took responsibility for the decision to run the Editor’s note and apologized for damaging the trust of readers and employees.

Mizuno, whose only previous byline in the paper had been an interview with the prime minister, did not walk back the changes, but said the paper would discuss its choice of language. “It pains us, as journalists, that this note has tarnished our reputation as an independent voice, ” wrote Mizuno, who did not respond to questions from the Number 1 Shimbun.

BUT NOT ALL THE reaction to the JT’s move was negative. Some welcomed it. In a Dec. 6 Twitter post retweeted over 8,000 times, American attorney and author Kent Gilbert who contributes a weekly column to the conservative tabloid Yukan Fuji called on his followers to send messages of support to the JT. And on Dec. 7, Twitter also saw Masahisa Sato, Japan’s State Minister for Foreign Affairs, wonder aloud whether the change was “the result of accumulated efforts or a symbolic change,” seeming to hint that there could have been outside pressure on the paper.

In response to questions from the Number 1 Shimbun, the Japan Times denied any government pressure behind the change. Asked whether it was motivated by South Korea’s decision to dismantle a Japanfunded foundation for comfort women, the paper said, “No. Our discussions regarding comfort women began long (almost a year) before this move.”

The paper’s new owner has generally played its cards close to its vest while quietly making changes. “Overall, the paper’s editorial policy has lurched rightward,” says Jeff Kingston, a history professor at Temple University Japan, whose long running column often critical of the Abe administration was terminated in 2017. The JT has increased columns by oped writer Kuni Miyake, a former Japanese diplomat and assistant to Akie Abe; meanwhile, syndicated American liberal columnist Ted Rall hasn’t appeared since October.

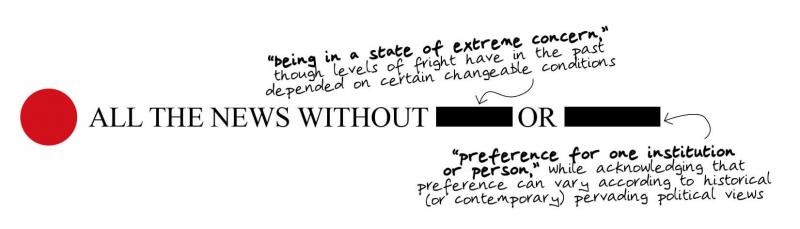

The Japan Times is Japan’s oldest English language daily. For over 120 years, it’s been a vital voice for Japan in the international community, surviving mergers, wartime state control and the decimation of newspapers amid digitization. In a market with countless online choices for news, aligning editorial views with government policy seems a surefire way of turning loyal readers off. After all, independence is a newspaper’s raison d’être.

Tim Hornyak is a freelance writer who has worked for IDG News, CNET News, Lonely Planet and other media. He is the author of Loving the Machine: The Art and Science of Japanese Robots.