Issue:

August 2025 | Japan Media Review

Price-fixing is rife in the apartment repair sector. Now authorities are taking action

Monthly building management fees (kanrihi) and repair fees (shuzenhi) have increased significantly for Japan's condominium owners in recent years. Management fees go toward the day-to-day running the building, while repair fees go into a fund that is used down the road for large-scale renovation. In the past, repair fees were usually set low by developers to make new condominiums more attractive to buyers. In some cases, though, the funds are insufficient, so when repairs are finally undertaken, there is not enough in the reserve fund and owner-residents have to cough up more money. The sharp increase in repair fees, which have gone up by 80% over the last 24 years, is a reaction to this reality, since more condos are reaching an age that requires large-scale renovations.

According to the construction ministry, the average monthly repair fee nationwide was ¥13,054 in 2023. Consequently, the reserve funds can be quite fat, depending on the size of the building and the number of residents. Construction companies specializing in residential buildings are losing business because of population decline and other factors, so they are eyeing these funds as they concentrate more on renovation work. A recent article in the Asahi Shimbun reported on a strange trend that seems to be related: non-residents impersonating residents to get into homeowners association meetings so that they can vote on approving plans for repairs. It's believed these imposters are working for construction companies, which could do with the work.

In May, two employees of construction contractors were arrested for trespassing after pretending to be residents of a condominium in Kanagawa Prefecture. Something similar happened at a condo in Chiba Prefecture, where a man who did not live in the building had attended 10 owners association meetings since July last year by pretending to be the son of an owner-resident.

A woman from a different condo who talked to the Asahi said that in March of 2024 she received a flyer in her mailbox from a marketing company that was soliciting interviewees for a survey. She answered the ad and eventually learned that the inquiring company was checking condo management associations to make sure they weren't wasting or otherwise misusing funds. The liaison asked the woman if he could use her husband's name to attend meetings. In return, she would be compensated on a monthly basis. She accepted the offer. Later, a different man contacted her saying he would impersonate her husband's brother, and thus needed personal information in order to make the masquerade more convincing. He even asked her for a duplicate key so that he could enter the building freely. She did as she was asked.

Someone from building management became suspicious and visited the woman. When she tried to contact the marketing company, she got no reply and eventually confessed everything to building management and later the police, who arrested one of the imposters in early June.

The non-resident mole's job is to sway the owners' association in ways that benefit their client, which is usually a construction contractor. They may be able to persuade the association to order repairs at an earlier date, for instance. Construction ministry guidelines recommend large-scale repairs every 15 years, but many experts say 20-25 years is fine for most newer buildings. Naturally, the imposter will also try to get the association to hire the contractor or building maintenance consultant they are secretly working for.

This would be difficult to pull off if owners associations weren't so weak to begin with. It is often hard to get owners to voluntarily attend regular meetings, so aggressive non-resident agents can be persuasive, especially if there is more than one.

Although the use of imposters to game the system in favor of contractors may not be that widespread, construction companies use other improper business tactics to achieve the same aims. In March, The Fair Trade Commission launched investigations into 20 major contractors it believed have formed dango (business associations) to fix prices for large-scale condo repair and renovation work. The dango system means that prices are already determined within the association. The FTC eventually added 10 more companies to its investigation.

Owners associations have two methods of choosing contractors. They either solicit the contractor directly by advertising for bids, or they hire a consultant who studies what work needs to be done and then goes out and finds the appropriate contractor through a bidding process. The consultant then monitors the work. The advantage of this method is that the contractor is supervised by a third party in the interests of the homeowners. However, the FTC believes that there is often collusion between consultants and contractors, which would be a violation of antitrust laws.

Another possible ringer is the company hired to manage the building. Many of these companies were given their jobs by the original developers of the properties and never replaced by owners associations. Sometimes these management companies are affiliated in some ways with contractors, and because of their expertise they often serve as voting members of owners associations.

Consequently, according to the Asahi, people who are considering buying condominiums, either new or used, should place as much importance on the owners association and collection of repair fees as they do on the price of the condo they want to buy.

In June, journalist Junichiro Yamaoka, who has written books about Japanese housing and real estate, ran a discussion on the web news site Democracy Times with Keiichi Sutou, a specialist in condo management, and Atsushi Yamada, a regular Democracy Times commentator who himself is presently the head of his condo owners association, which this summer is carrying out major renovations to their building.

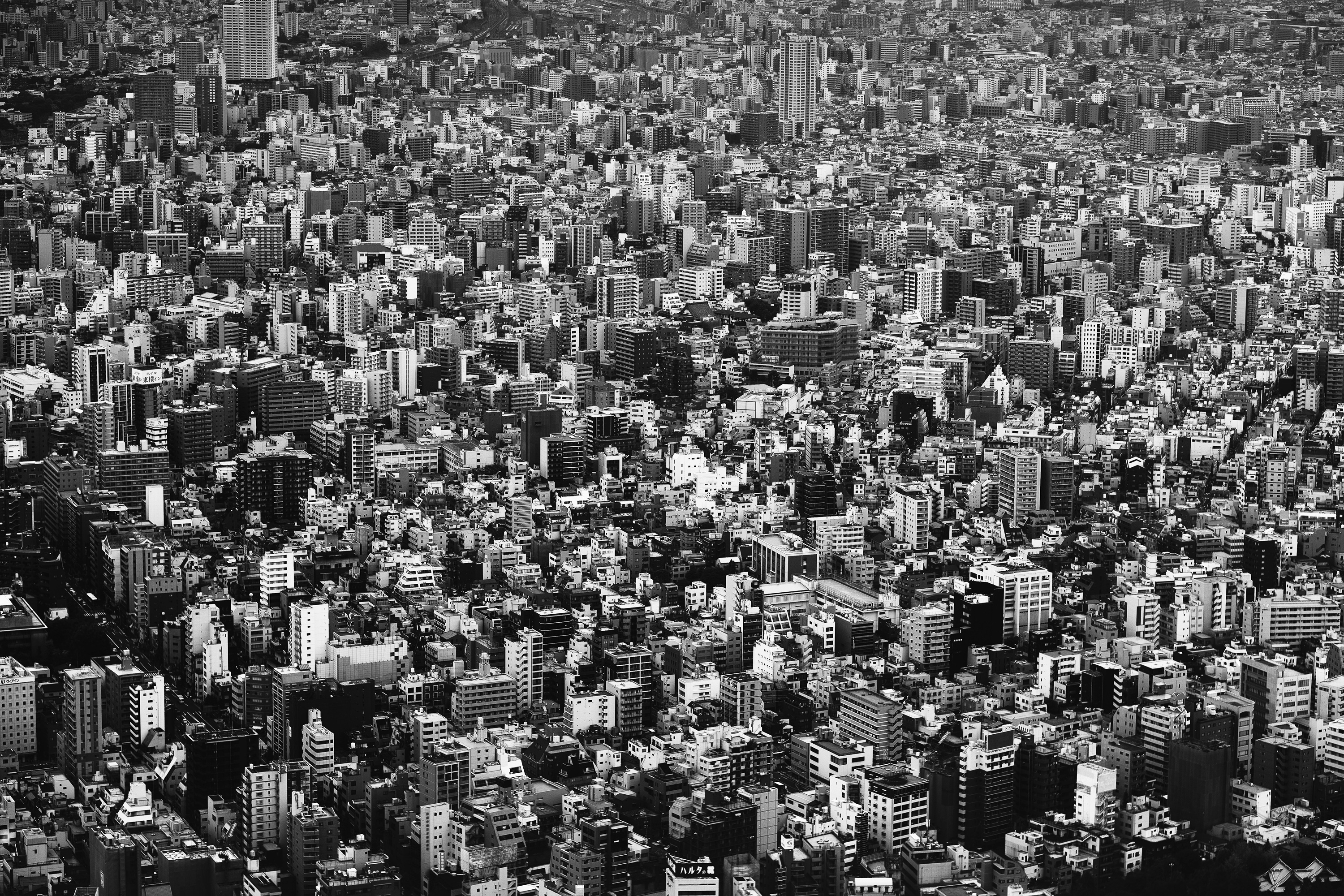

Yamaoka pointed out why the dango problem had become widespread. In Tokyo, he said, 30% of residents live in condominiums, and 20% of Japan's 7.4 million condo units are over 40 years old. That's a lot of money in saved repair funds, which construction companies naturally covet. Yamada added that in his own 40-year-old building of 319 units, more than 25% of the owners are over 70. In the past, these owners often carried out repairs every 12 years, handling the minor work themselves (An outside company will charge ¥7,500 to change a light bulb. But now that they are too old to do that kind of work, they hire a contractor to do all the repairs and renovations on a large scale. The work will cost them all the money they have in their repair savings fund.

Large-scale work includes painting the exterior of the building, waterproofing the roof and other surfaces, fortifying steel pillars, elevator maintenance, and repairing common electrical and water facilities. It also may include repaving areas within the property that are used by vehicles.

Sutou explained how the hired consultants work with construction dango. When the consultant puts out a bid for work, it lists strict criteria for potential bidders, such as having at least ¥50 million in paid-in capital, or a history of more than 100 previous renovation jobs. These criteria effectively and considerably reduce the pool of potential bidders, leaving only major contractors. In some areas, especially the Tokyo metropolitan region, only major contractors would qualify, and so the consultant can easily choose bidders who belong to the same dango. Within the dango, of course, the “champion”, meaning the company with the winning bid, has already been chosen, so all the firms set their bids high while the champion sets its bid slightly lower and gets the job.

However, according to Sutou, even the low bid is set artificially high. For instance, he mentions a case in Saitama Prefecture where a 200-unit building hired a consultant to find a contractor, and the winning “low” bid was ¥400 million, meaning each household would pay ¥2 million out of their contributions to the repair fund, but the actual cost of the repairs would only be about ¥200 million. The consultant passed on the work specifications to the dango secretly, and the dango decided how much to charge, inflating the work cost twofold. Sometimes, the consultant gets this information from the building management company, which will receive a “rebate” later for its services. The consultant also receives a kickback from the dango.

The consultant and the contractors count on the likelihood that the owners association is made up of “amateurs” and don't really know the value of the work they are requesting. Such a scheme becomes difficult if the owners association contains people who are knowledgeable about real estate and building construction, so Sutou advises owners associations to seek out people in their building who may have this knowledge.

In the Saitama case, the owners balked at the estimate given for the bid and asked the consultant for a more detailed estimate, saying they would choose the contractor themselves. The consultant tried to convince them that they weren't knowledgeable enough to do it themselves. When the owners ignored this warning, the consultant sent a letter signed by a lawyer threatening the owners that if they chose their own contractor, the consultant would not monitor the work. The owners, sensing extortion, simply fired the consultant. They eventually hired a contractor who charged them ¥200 million for work that the dango contractor estimated would cost ¥400 million.

Sutou has posted an episode on his YouTube channel showing him advising owners associations on how to carry out large-scale repairs. He says associations should avoid consultants who set very high conditions for potential bidders. Owners should be suspicious if the amount of the winning bid is very close to the full sum of money in the repair fund. Under those circumstances, the owners should also ask the consultant for examples of bid advertisements from past work to check what sort of conditions are listed and which contractors were chosen. As he points out, the goal of a dango is to get the condo owners to spend everything in their repair fund. In a best case scenario for the dango, the owners will even borrow money in order to cover the winning contractor's estimate.

According to the Asahi Shimbun, a nationwide condominium management federation that advises individual owners associations recommends that when they make a contract with a consultant that they insist on the inclusion of a term explicitly prohibiting the hiring of construction companies involved in dango and price-fixing. It seems to go without saying, but it’s better to have everything in writing.

Philip Brasor is a Tokyo-based writer who covers entertainment, the Japanese media, and money issues. He writes the Japan Media Watch column for the Number 1 Shimbun.

Sources