Issue:

August 2025 | Ripping Yarns

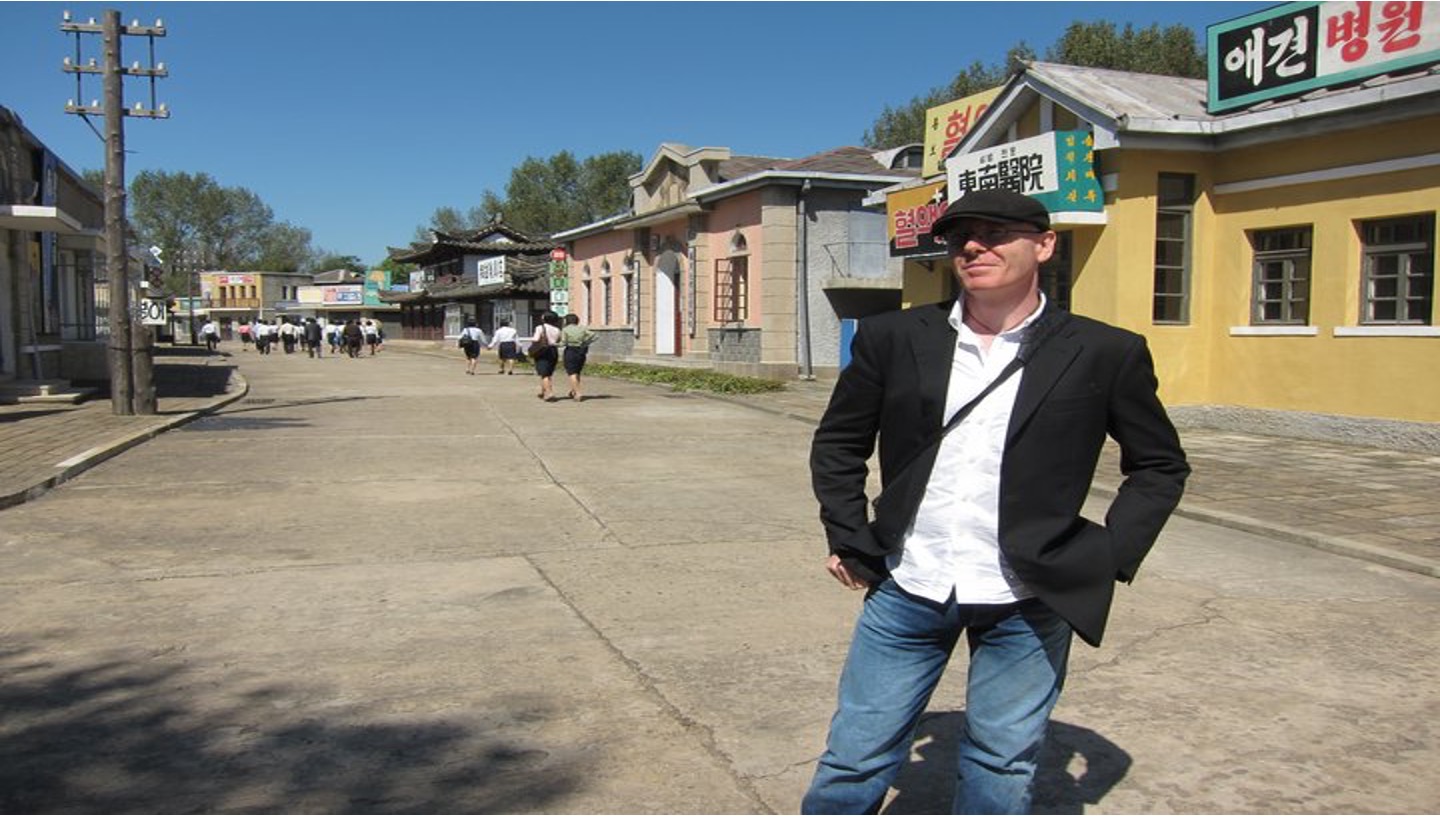

David McNeill’s unauthorized stroll around the North Korean capital ended in tussles and apologies

In September 2010, delegates began gathering for the first conference of North Korea’s ruling Workers' Party in decades. Top of the agenda was a successor to Kim Jong-il, who was recovering from a stroke suffered in 2008. Among those in Pyongyang to witness this hereditary transition of power in the Kim dynasty was a group of Western journalists pretending to be tourists and English teachers.

We arrived, via an expensively purchased visa from the North Korean Embassy in Beijing, on an Air Koryo plane serving mystery-meat burgers and watery Taedonggang beer. At the airport, our phones were confiscated and put into sealed plastic bags, an inconvenience that left us mostly at the mercy of state-run media but which turned out to be quite blissful. No nagging editors could reach us there.

From the 40th floor of the Yanggakdo hotel, the dim illumination from street lamps and low-watt bulbs in apartment buildings was a telltale sign of the city’s lack of fuel and creaking electricity grid. The brightest lights shone on the architectural baubles, idolatrous murals and giant statues of the Kims dotted all around the city. Pyongyang at night had an eerie, waxy pallor that couldn’t disguise its slow decomposition.

Our guides treated us like antibodies around a virus, hustling us from one approved site to the next and isolating us in our hotel, built on an island a mile south-east of the city centre. The only way to see behind the Potemkin Village façade was to give the guides the slip, so Richard Lloyd Parry and I found ourselves walking across the bridge from Yanggak Island at dawn, to the puzzled looks of North Koreans.

Many were just starting their day, going to work on foot, by bicycle or in the city's rusting electric tram system. Women crimped their hair as they hurried to the tram; men walked their daughters to school. A typical morning anywhere, except this was modern life stripped bare: no iPods, jeans, T-shirts or sneakers, which were banned as foreign affectations.

As we walked into the backstreets, the mask began to slip. Here the roads were potholed, the people scruffier and more sullen, and some appeared to live in slum-like conditions. Rounding a street, we stumbled across a group of about 200 people huddled around a makeshift street market, our first concrete sign that the country's state-controlled distribution system was shot.

The crowd eyed us nervously – markets such as this were illegal because, among other things, they struck at the heart of the official claim that the state would provide all; and they allowed people one of the few places outside official gatherings to meet and talk. Women on haunches rolled out slabs of meat, vegetables, apples, even underwear, ready to disperse at the first sign of trouble. I raised my camera to take a picture, and just as Richard told me to be careful, the crowd came for us.

We attempted to walk away as our bags were violently tugged by a man in a scruffy army uniform who demanded our cameras. We had no choice if we were going to safely escape. We surrendered our cameras. Our interrogator tried to march us to what looked like a police station, and we shook him off, before making a wrong turn and walking straight into a phalanx of green uniforms – a guard post.

The previous year, Americans Euna Lee and Laura Ling had been accused of espionage after being captured reporting along the border, held for months and only freed after a rescue mission by Bill Clinton. Back in my hotel room were my press ID from Japan, business cards and a laptop with articles I’d written about Kim, including one headlined “Schooldays of a Tyrant”. If news of our arrest stayed with the neighborhood goon squad, we thought, we might get away with a ticking off from our guides. If not, who knows?

In broken English, we began explaining that we were in town as delegates to the Pyongyang International Film Festival and had simply gone for a stroll. As we talked, an army vehicle arrived and a soldier approached carrying our cameras, which he’d retrieved from the crowd. The men fiddled awkwardly with the unfamiliar technology before giving up and demanding we show our pictures.

My memory card didn’t work – it was probably damaged in the melee. Richard's showed only a single blurred photo of the market and several dozen of his blonde, then one-year-old daughter. When the men saw her, they softened. They asked her age and swapped cigarettes. A group of more senior soldiers drew up and we watched as they mimed the story of how the two six-foot foreigners had been mugged of their cameras and money by the much shorter Koreans, drawing laughter all around.

We were ordered into a van and driven back to the hotel where our guide, Mr Cha, was waiting for us. His face registered shock as they told him the news. He was responsible for us and shared the consequences. Our journalist colleagues, three Scandinavians, a Frenchman and an American – also posing as tourists – would suffer the collective punishment. A makeshift tribunal was hastily arranged, chaired by the boss of the travel company.

In the gravely tones of a chain smoker, the boss intoned that our actions had inflicted a “black stain” on improving relations between his country and Britain – it wasn't the time to point out that I was Irish. We would be confined to our hotel and write a letter of apology “from our hearts”. The letter was read out, the boss pronounced himself satisfied but our camera memory cards, containing four days' worth of photos, were kept.

It was better than the alternative. A tearful Mr Cha later allowed us to leave the hotel to attend the closing ceremony of the film festival. Over a final drink, he toasted us. But the memory cards stayed confiscated, all except a handful of anodyne photos. “I hope you understand our country better and will come back,” he said over a beer. “We want people to like and respect our country.”

David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s Professional Activities Committee. He was previously a correspondent for the Independent, the Economist and the Chronicle of Higher Education.