Issue:

August 2025

The diplomats who turned to writing about crime, starting with Robert van Gulik

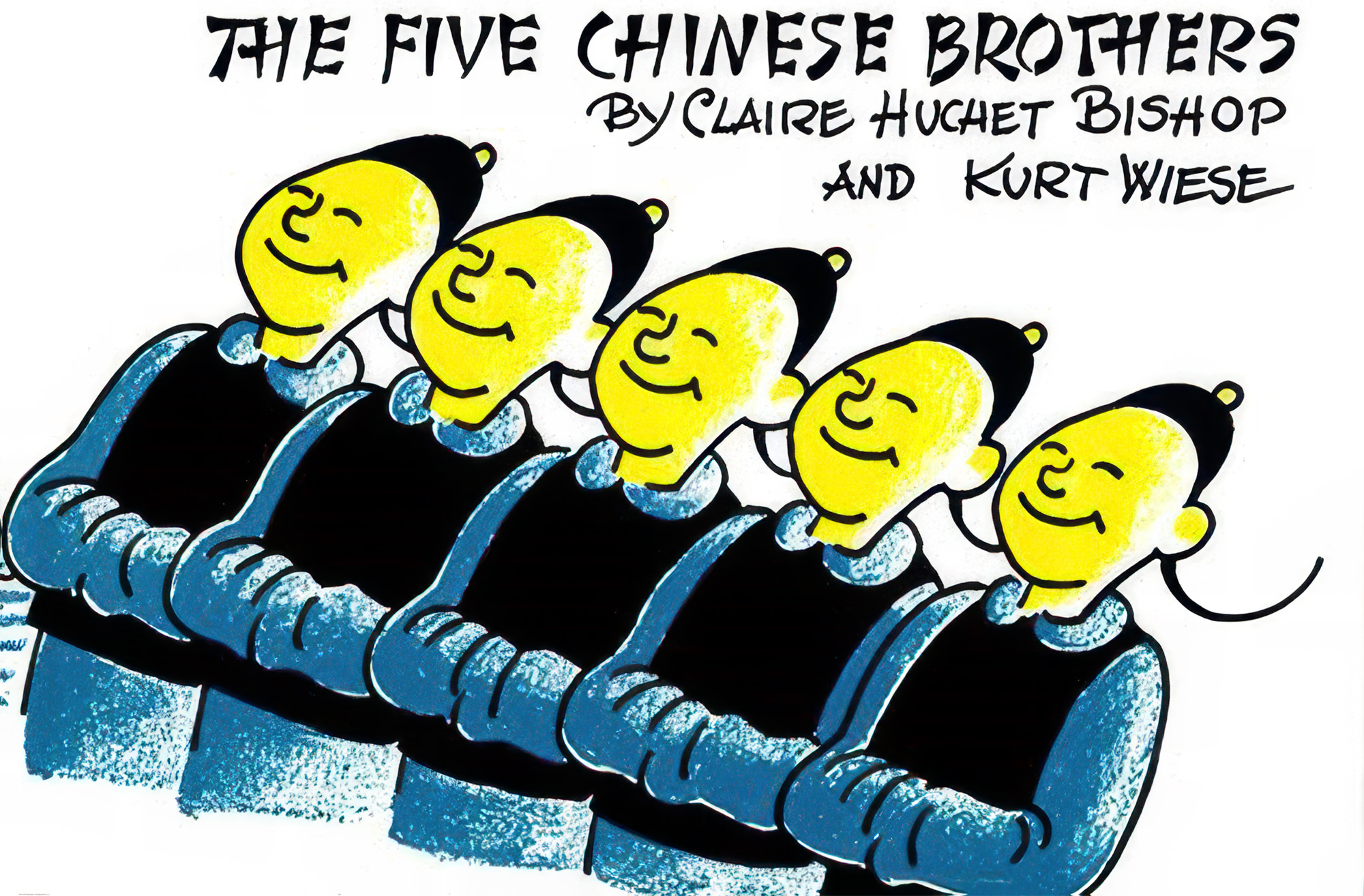

Who, among us, cannot recall a favorite book from early childhood? In my case, it was one I checked out from my elementary school library in Canandaigua, New York, titled The Five Chinese Brothers. Originally published in 1938, it was authored by Claire Huchet Bishop and illustrated by Kurt Wiese.

The book was based on a famous old Chinese folktale about five identical brothers, each with an unusual ability, When one brother is sentenced to death for a crime he could not help committing, each brother stands in for him in turn, using a special talent to escape capital punishment. After four tries, the judge decides the brother sentenced to death must not be guilty, and all five brothers live happily with their mother for many years.

A dozen years would transpire from the time I read that book until my arrival in Okinawa, 60 years ago this month. I don't recall the details, but one day I happened to encounter a mystery short story about a magistrate in ancient China named Judge Dee, written by Dutch diplomat and sinologist Robert van Gulik, and my childhood fascination with law and order in China was rekindled.

For over 1,000 years, “righteous officials” – incorruptible men, beloved by the downtrodden, who upheld the nation's strict legal code – have figured in stage plays, novels and more recently cinema and television. Among the Westerners who took notice of this was Canadian-American author Vincent Starrett, who in 1942 published Bookman's Holiday: The Private Satisfactions of an Incurable Collector. The book contained a remarkably well researched, 23-page chapter titled “Some Chinese Detective Stories”.

While sojourning in China in 1940, Starrett had engaged the services of a multilingual student named Yi Ying to compile materials related to China's traditional stories of crime and detection. Ms. Yi clearly outdid herself: Starrett's 6,000-word essay, gleaned from her research, identifies five historical individuals whose stories found their way into works of popular fiction. They included Bao Zheng (999–1062 CE), also known as Bao Gong, whose name remains venerated in China to this day.

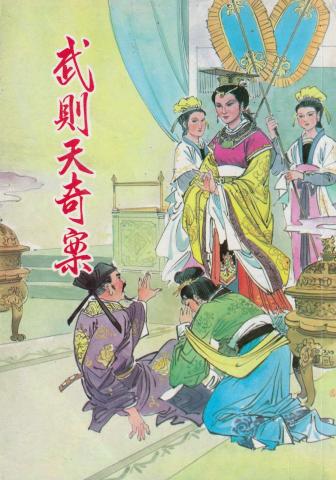

Another of the five was Di Renjie (630-700 CE), who rose through the ranks of China's civil service in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) to become the nation's prime minister under Empress Wu.

About Di, Starrett wrote: “Another volume of great jollity and entertainment is the Wu Zetian Qi An, a title which may be loosely translated as ‘Strange Cases in the Reign of Wu Zetian.’ This is really a very amusing book indeed...The Empress Wu, who lived early in the seventh century, was by all accounts a woman of great sprightliness and wisdom, at once a courtesan of considerable attraction and a law-giver of sound and benevolent judgment. Her reign was a magnificent one, and during its fantastic march there was much, it would appear, for the great magistrate Di Renjie to whet his wits upon.”

Starrett continues: “There is also a snake story that is vaguely reminiscent of ‘The Speckled Band’ — a tale of Sherlock Holmes that was to be written some centuries later. In the earlier story, a number of persons are dead by poison and, as usual, there is no clue to the murderer, save that his poison has been taken in a pot of tea. Di Renjie, however, has his own ideas about what has happened and proceeds to re-enact the crime. Taking possession of the place, he sits around pontifically and orders the kitchen-servant to boil innumerable kettles of water. Nothing whatever happens for a time; then as one begins to fear that for once the fathomer is doomed to failure, the rising steam effects its purpose. The ugly thing on the thatched roof again thrusts its head through the aperture noted by the detective, and, coiling downward, again releases its venom into the water.”

Starrett was given to wonder why these alluring old stories had not caught on in foreign translations. The answer, to cite prolific Chinese author Lin Yutang, was that "the Chinese love for the supernatural has invalidated the Chinese mystery story and makes the detective story (as known in the West) impossible". Yet, Starrett concluded, "it may be that what is needed is simply a man of genius to pave the way for a new dispensation. A really great detective novel by the right man might exorcise all the devils and ghosts and goblins of China".

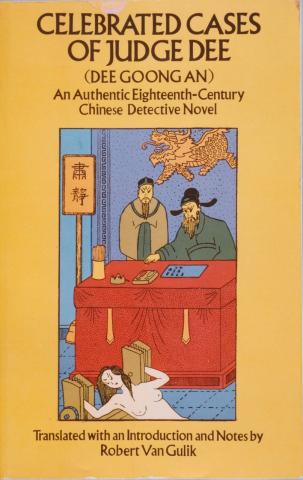

It took just seven years for Starrett's prophecy to come true. In 1949, a Tokyo-based Dutch diplomat named Robert van Gulik arranged for the private printing of 1,200 copies of his English translation of the abovementioned work. Titled Dee Goong An: Three Murder Cases Solved by Judge Dee, van Gulik also included several of his own illustrations in Chinese style. This first introduction of Judge Dee to English-speaking audiences remains a significant volume in the history of detective fiction. With the assistance of a trusted adviser and the three lieutenants who comprise his personal staff, the magistrate solves three seemingly distinct crimes that turn out to be interconnected. The first might be called "The Double Murder at Dawn," the second, "The Strange Corpse," and the third, "The Poisoned Bride."

As Henry Wessells wrote in the AB Bookman's Weekly edition of 1 September 1997, "In his translator's postscript to Dee Goong An, van Gulik had written, 'I think it might be an interesting experiment if one of our modern writers of detective stories would try his hand at composing an ancient Chinese detective story himself.' No one rose to the challenge, and during 1949 van Gulik himself began to compose, in English, an original Chinese detective novel, "borrowing Judge Dee and his four lieutenants Hoong, Ma Joong, Chiao Tai, and Tao Gan, with their main characteristics. 'My English text,' as he later wrote, 'was meant only as a basis for a printed Chinese and/or Japanese version, my aim being to show modern Chinese and Japanese writers that their own ancient crime-literature has plenty of source material for detective and mystery stories.'"

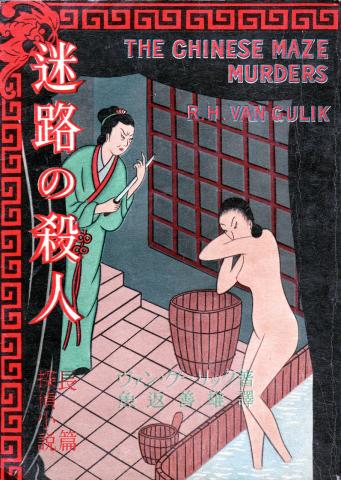

The Chinese Maze Murders would be the first of 14 Judge Dee novels, two novelettes and one short story collection, the last of which, Poets and Murder, was published in 1968, a year after van Gulik passed away.

A recent paperback version of van Gulik's translation, Dee Goong An (Dover Publications, 1976). The Chinese sign reads su jing (Be Silent), the equivalent of “order in the court”.

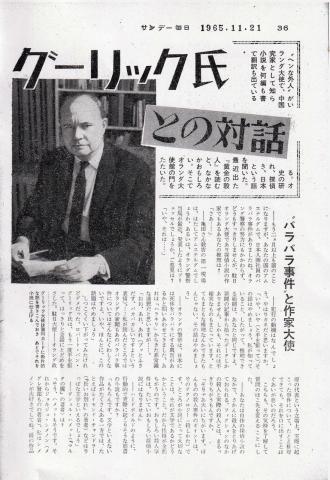

While serving as Netherlands' ambassador to Japan, Robert van Gulik was interviewed about his novels in the Sunday Mainichi magazine of Nov. 21, 1965.

By 1951, Starrett and van Gulik had begun corresponding and not long afterwards, Starrett received a copy of The Chinese Maze Murders, which he reviewed in the Chicago Sunday Tribune of 16 June, 1951. He gave the novel high marks, writing, "… unless you are a student of the subliterature of Chinese empire days, don't expect to read anything like anything you have ever read before. The author has taken three plots from ancient Chinese sources and reworked them in one continuous story, retaining the traditional device of letting the detective solve a number of cases simultaneously".

The Chinese Maze Murders was also translated into Japanese by a sinologist friend of van Gulik, and accepted for publication by Kodansha. This set off a cultural clash of sorts, because the Japanese publisher thought the book would sell better with a female nude adorning the cover.

According to Wessells, van Gulik informed Kodansha that "I could not do that, because I wanted to keep my illustrations in genuine old Chinese style, and that in China, owing to the prudish Confucianist tradition, there never developed an artistic school of drawing nude human bodies. The publisher, however, wanted me to make sure of this anyway so I wrote identical letters to a few dozen antiquarian booksellers in China and Japan of my acquaintance, asking whether they had Ming prints of nudes … All answers were negative, except for two: a bookseller in Shanghai wrote me that one of their customers possessed a few erotic albums of the end of the Ming period and was willing to let me have tracings of these pictures; and a curio-dealer in Kyoto informed me he had a set of actual Ming printing-blocks of an erotic album, containing large-size male and female nudes. I purchased these blocks, and had tracings made of the albums of the Shanghai collector.”

He added: "This is one of the many cases where the writing of my detective novels had a direct bearing on my orientalistic research work."

Van Gulik continued to illustrate his Judge Dee novels, drawing on tracing paper because he found it particularly difficult to reproduce characters' faces. His illustrations also reflected the morals of the times, in that his portrayals of female nudes always concealed women's bare feet – which men in olden times considered the most erotic part of the female anatomy. In one novel, for example, a woman shown swimming nude in a river has her feet artistically concealed by a drifting plant.

Van Gulik's Judge Dee stories also carry an air of authenticity because many were sourced from accounts of actual cases that appeared in a 13th century guide for magistrates, T'ang-yin-pi-shih, attributed to Southern Song Dynasty official Gui Wanrong. Translations of the book were used in pre-modern Korea and Japan, and van Gulik later translated it into English, with annotations. In 1956 it was published under the title Parallel Cases from under the Pear-Tree.

In The Willow Pattern (1965), van Gulik cleverly spliced some contemporary Western culture into his ancient Chinese narrative. The original Blue Willow design, painted in the style of Chinese porcelain with pagodas, a weeping willow tree, an ornate boat floating on a lake and two birds in the sky, originated in late 18th century England by engravers such as Thomas Minton and Thomas Turner.

It was a tribute to van Gulik's creativity that he could adopt a design crafted in 18th century England and weave it into the plot of a mystery for Judge Dee to solve while in the midst of an epidemic in ancient Chang'an.

Van Gulik's Judge Dee novels not only remain in print, but tales about the righteous Tang official by other authors have been enjoying an upsurge of popularity in recent years. Some of these works closely emulate the characters and style set down by van Gulik. Chinese-American author Qiu Xiaolong, a scholar of classical Chinese literature, has written two that more closely reflect historical accuracy (with allowances for some poetic license). In a more extreme example, Judge Dee appears as a sadistic villain in iconoclastic author Dai Sijie's 2003 novel Mr. Muo's Travelling Couch, which recounts the bizarre travel experiences of a Chinese man whose philosophy has been influenced by French psychoanalytic thought.

This year Mark Schreiber celebrates his 60th year in Asia. He is currently working on an essay about Japanese weekly magazines that will appear in an anthology about Japan's mass media.