Issue:

August 2025

The media must find a way to counter the disinformation that is turning Sanseito into a genuine political force

In the lead up to and aftermath of the July 20 upper house elections, the relatively new political party, Sanseito, has garnered significant media attention in Japan and beyond.

Sanseito, which translates roughly as the “political participation party”, describes itself in English as “The Party of Do it Yourself!!” It was formed in 2020 in response to protests against the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions, mask-wearing guidelines, and vaccinations. In 2022, the party gained a seat in the upper house and became a national political force by winning more than 2% of the vote.

Sanseito had already attracted international attention when it held only one seat. In June 2022, the Sanseito Q&A Book: Basic Edition triggered accusations of antisemitism directed at the book’s editor, Sohei Kamiya and his nascent political party. The book explains basic elements of Sanseito’s platform and policies, while also sharing a larger worldview. The party gained widespread coverage in Jewish-serving publications for a passage that began by positing the question, “What do members of Sanseito mean when they say, ‘Those forces’?”

The book explains: “This is a name for several organizations which are led by international Jewish capital. They effectively control Western society and have been targeting Japan for hundreds of years.”

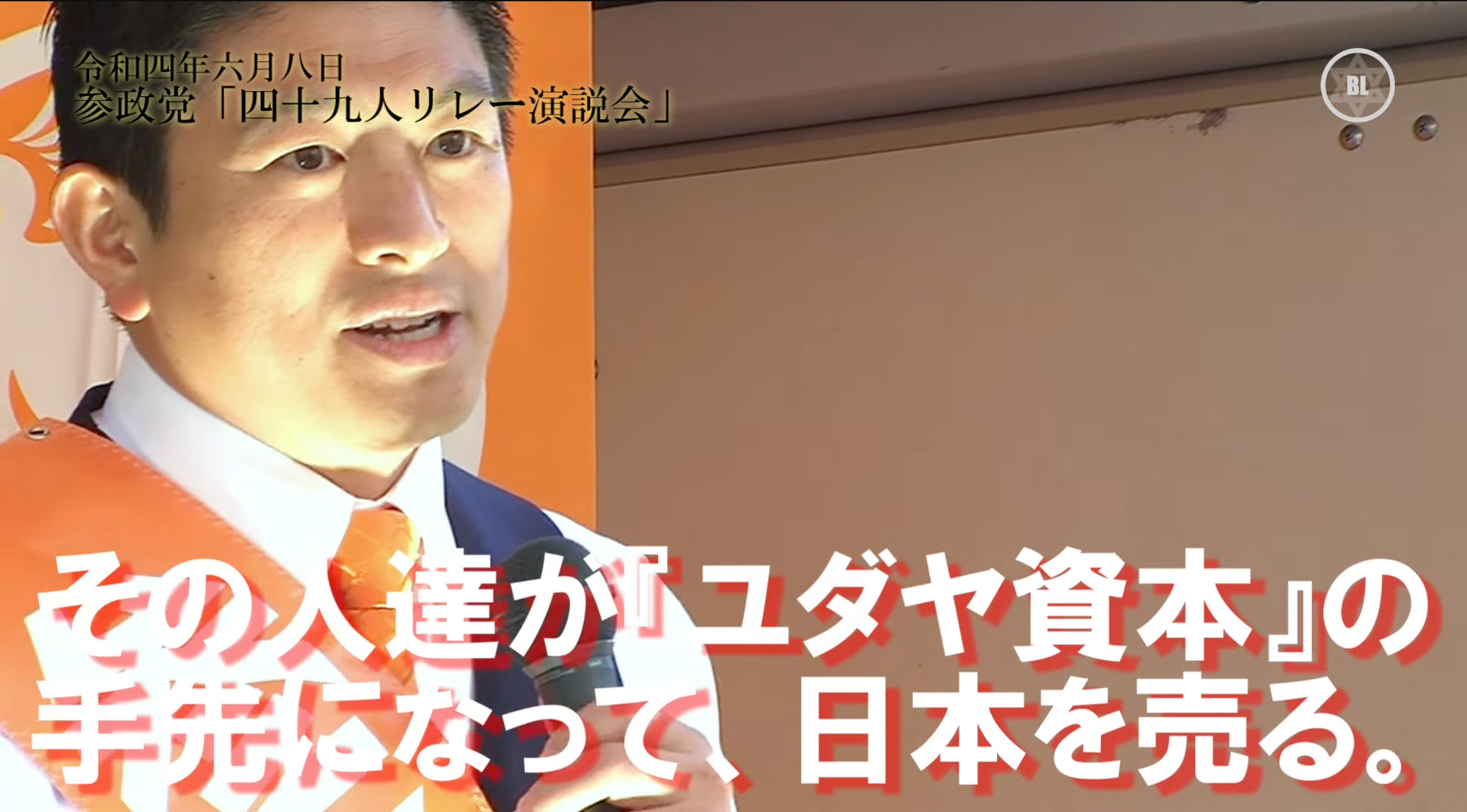

This passage drew condemnation from the Israeli ambassador to Japan, Gilad Cohen, who protested to the Japanese government. Seemingly a throwback to the bygone era of conspiratorial and discriminatory yudaya bukku (Jewish books) published during the bubble economy and in its aftermath, Kamiya repeated this rhetoric during a 2022 stump speech, saying, “Do you think these people [Sanseito’s candidates] will become Jewish capital’s pawns and sell out Japan?”

Despite this history of incendiary claims, before the July 20 election, polls were predicting that Sanseito would make substantial gains. A Kyodo News poll conducted July 5-6 had Sanseito ranked second for votes in seats decided by proportional representation.

Situating Sanseito’s platform and policies in a comparative light, news outlets have frequently characterized the party as “anti-immigrant”, “anti-globalist,” and “far-right”. But a survey of media outlets reveals a particularly widespread categorization:

- In the Guardian on Friday, July 25: “Japanese First’: breakthrough by rightwing populists sparks fears of anti-foreigner backlash in Japan”.

- In an article back in June, Kyodo News explains, “Younger Japanese drawn to anti-immigrant populist Sanseito”.

- On July 16, the Asahi Shimbun observes, “Sanseito retains populist message after silencing vaccine stance.”

- A July 22 Wall Street Journal article referred to it as. “populist Party That Began on YouTube Helped Disrupt Japan’s Ruling Coalition.”

What is it, though, that makes Sanseito “populist”?

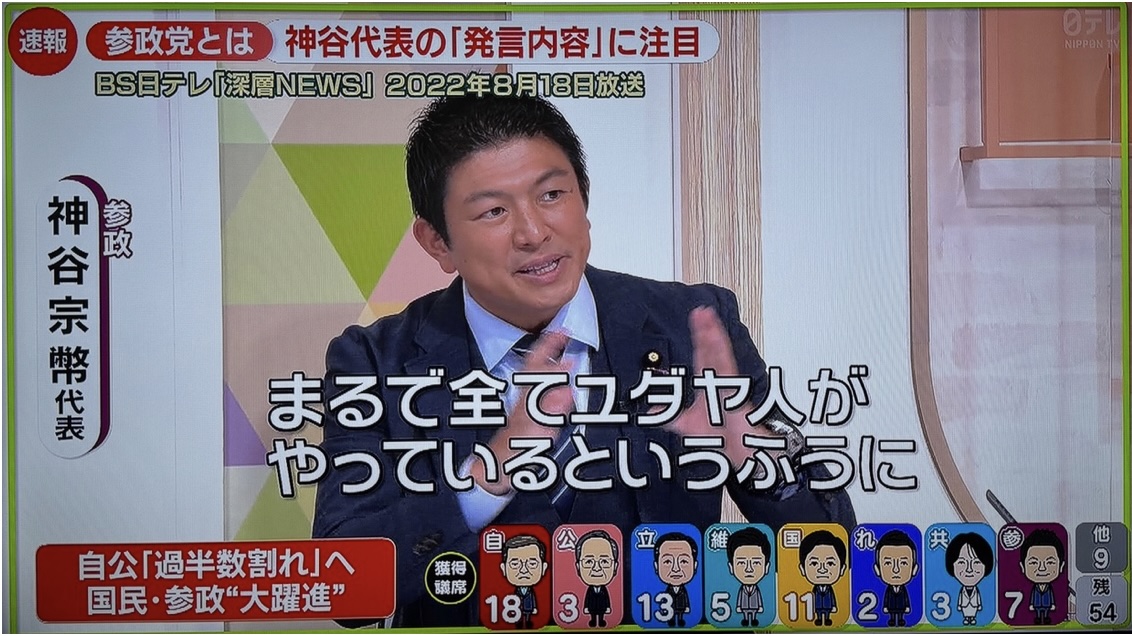

In an interview with Nippon TV on August 22, 2022, following his election to the upper house as Sanseito’s sole representative, Kamiya was asked about claims made regarding “those forces” in the Sanseito Q&A Book: Basic Edition. He responded: “It was written a bit poorly … while it’s the truth that Jewish capital is involved, I think it was a bit wrong to write it in a way that people could misunderstand as saying that all Jews are a part of it. And, so, in the future, I think we need to revise it.”

In a post-election article in the academic journal, Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Professor Fabian Schäfer at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg outlines Sanseito’s populism as centering on three issues: “…the perceived threats from “globalist” elites … an “uncontrollable” influx of allegedly criminal foreigners, and a “corrupt” political establishment “burdening” young people with taxes”.

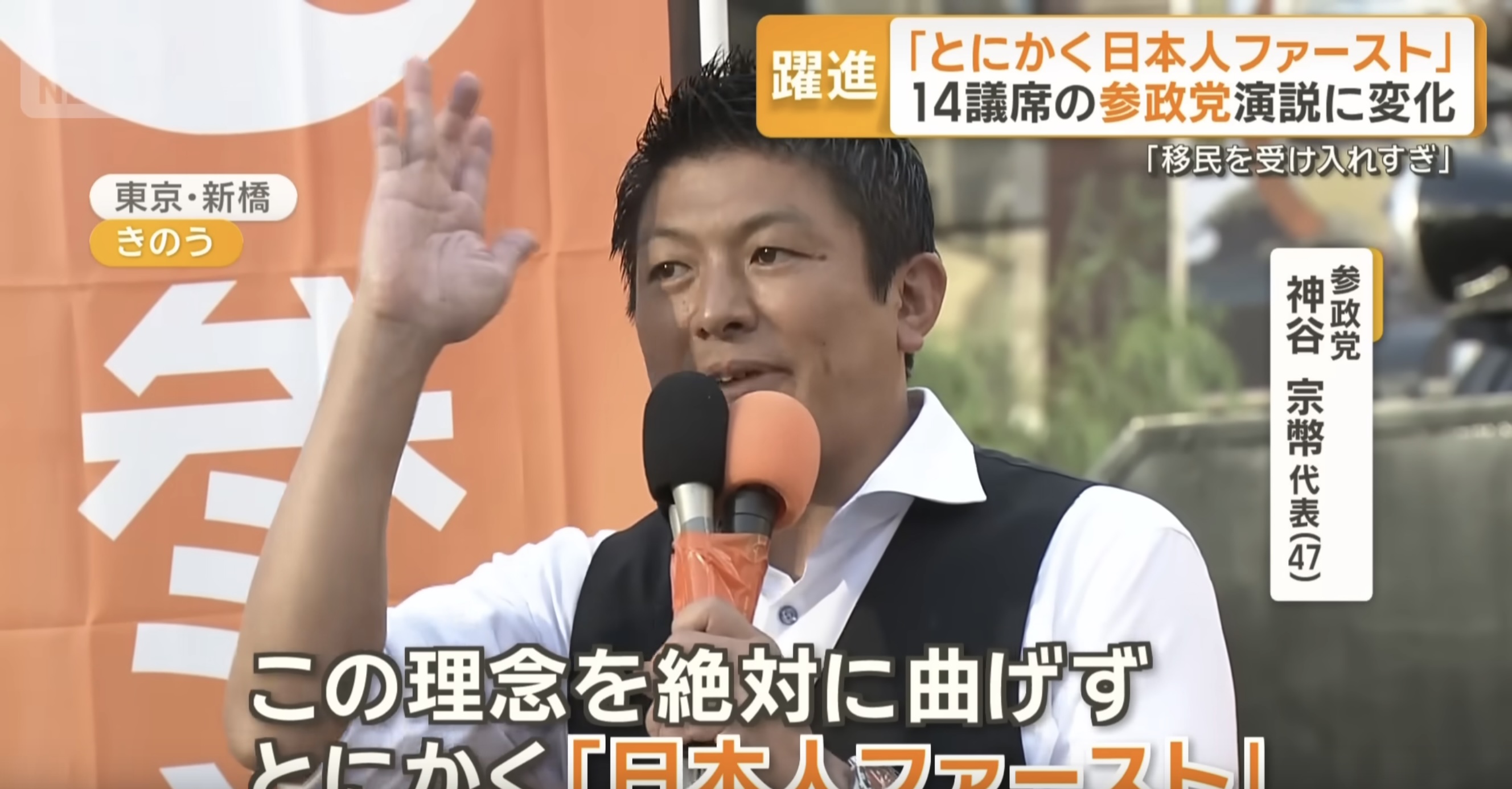

Sanseito’s populism is not reducible to rhetoric alone. Instead, as Wakaba Oto of Tokyo Weekender writes: “ … the party is gradually redrawing the boundaries of what’s politically acceptable — what can be said, proposed and believed ... already, we’ve seen a shift: mainstream politicians hardening their stance on immigration, leaning into rhetoric around “traditional values” and “Japanese uniqueness.” What once sounded fringe is becoming part of the debate”.

Both reporters and researchers have stressed that whether Sanseito can maintain the momentum from this election or not, its campaign tactics will have a profound impact. This cannot be measured by the current 15 seats in the upper house. Because, as Schäfer explains in the Asia-Pacific Journal: “… the populist agenda aims to reshape political discourse, influence political communication, and undermine democratic institutions through strategic attacks. Their ultimate objective is to normalize distrust in democratic norms and institutions, causing long-term damage that cannot be easily reversed, even if the party loses influence or dissolves”.

In her write-up for Tokyo Weekender about Sanseito before the July 20 election, Oto wondered “whether Japan’s civil society, media and institutions are ready to respond before these shifts become entrenched” when comparing Sanseito to other populist movements.

Categorization is often a guide for readers as well as an implicit argument: the shared features of seemingly distinct phenomena – in this case, political movements – can be better understood through the attributes they share. But, per Oto’s provocation, what can highlighting Sanseito’s parallels to Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” movement, the Alternative for Germany’s (AfD) continued electoral strides, or figures like Argentina’s Javie Milei or Italy’s Giorgia Meloni, help us understand what comes next for this rising party?

Sanseito’s candidates – and particularly Kamiya – have made acerbic comments about foreigners, including a June 21 speech in Tokyo in which he said, “Foreigners tend to forge anything and are good at finding legal loopholes.” That kind of rhetoric has gained press coverage worldwide, as seen in Deutsche Welle, which quoted Kamiya as saying that foreign workers had often “turned to criminal organizations to make money, such as through robbery, or the widely repeated Sanseito assertion that Japan faces a “silent invasion” of foreigners. Such caustic statements about perceived foreign threats to Japan are not limited to Kamiya – one Sanseito candidate claimed in a July 5 speech that “If the number of foreigners increases too much, security will decline, society will collapse.”

However, at a July 3 press conference at the FCCJ, Kamiya argued that Sanseito was in favor of “global harmony and mutually beneficial international economic relations,” adding that “We are not in any way intending to exclude foreign workers who are here legally.” He claimed that Sanseito’s policies and rhetoric are “not based on xenophobia.”

Like Sanseito’s anti-Jewish statements, this is not an anomaly, but a pattern. Kyodo News reported that during a July 15 stump speech in Tottori, Kamiya proclaimed that the Japanese government was “trying to keep the country running by injecting foreign labor and capital. It's like national doping.” Using an analogy to someone reliant on energy drinks, he was quoted as saying, “Using power from outside to run the country is heretical.” He then said, however, that the remark was just “an example”, and that arguing for restrictions on immigration was “not discrimination”.

Kamiya and Sanseito officials will offer controversial political remarks only to claim plausible deniability for blatantly norm-violating comments. This occurred multiple times during the upper house campaign. On July 3, Kamiya said at campaign speech: “We were wrong up until now, such as (promoting) gender equality. Although women's participation in society is a good thing, only young women can have children … older women cannot have children.”

Yet, the livestream of this speech suddenly cut video and audio off during this portion, only to then resume moments later. Sanseito officials claimed that this was due to the hot weather. In a similar vein, during a July 18 speech, Kamiya used a slur for Koreans, only to then quickly say, “You can cut that … I’m sorry. I will amend that.”

The Osaka-based Korea NGO Center sent Sanseito a protest letter challenging Kamiya’s prompt apology for the July 18 incident. "Words spoken by a politician representing a political party bear significant influence and cannot be easily dismissed as if they were never uttered,” it said.

The letter rightly states that politicians and political parties’ speech have consequences. Kamiya and Sanseito’s frequent pivots between jarring, general statements about foreigners in toto and subsequent mitigation and/or qualification are a pattern, and merit being covered as such rather than taking these statements in isolation.

Such statements make apparent Sanseito’s cynical attitude toward social norms. In statements such as Kamiya’s claim on July 21 that “We have no intention of discriminating against foreigners, nor do we have any intention of inciting division,” one is struck by contemporaneous accounts, such as a Kyodo News report about a Sanseito event in Wakayama. The June 24 report quotes participants as saying, "Japan belongs to the Japanese people, and foreign ownership of Japanese land is not permitted," and “… (foreigners) have to fulfil their obligations as human beings, and then we can teach them their rights”. This Kyodo report suggests Sanseito’s base is receiving particular messages. This is echoed by reports in the Asahi and from Reuters, which state that voters are attracted to Sanseito because of its rhetoric.

The recent history of populism elsewhere suggests that Sanseito’s backpedaling, hedging, mitigation, and qualification are part of a process whereby the political discourse in a nation gradually shifts and accommodates previously unconscionable positions. A June NHK poll that found 64% of respondents “strongly agreed” or “somewhat agreed” with the statement that “Foreigners are treated more favorably than they should be in Japanese society.”

Highlighting an ongoing pattern, Kamiya was asked by a reporter at a post-election press conference: “Do you think that foreigners receive special treatment in Japan?” To which he responded, “Foreigners receiving special treatment … In Japan, I don’t really think that’s the case.”

In her 1967 essay, “Truth and Politics,” German-Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote: “The result of a consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth is not that the lie will now be accepted as truth and truth be defamed as a lie, but that the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world—and the category of truth versus falsehood is among the mental means to this end – is being destroyed.”

After Trump became president-elect in November 2016, New York Times opinion columnist Jamelle Bouie summarized Arendt’s attitudes with a modern urgency, positing that Arendt’s analysis of far-right movements in Europe was that they, “… didn’t lie to obscure the truth; they lied to signal what would eventually become truth”.

To look at Sanseito’s embrace and spreading of misinformation, from false claims about vaccines to factually untrue claims of rising foreigner-committed crimes, runs counter to the lessons learned by reporters and scholars the world over from the rise of populist movements. Rather than treating such statements as betraying truth in a way somehow unique and at odds with politics, it is prudent to observe the lessons of populism elsewhere: misinformation is a strategy, but only when populist rhetoric is observed in the longue durée. Merely expressing outrage at each violation of civic norms and fact-checking it does not constitute a bulwark against the erosion of democratic liberal norms.

Labeling Sanseito’s politics as “populist” may be effective shorthand, but there is great importance in unpacking this term for the media’s readers. For many, comparing Sanseito to MAGA or the AfD may carry a ring of familiarity, but not much more. Rather than relying on shorthand, there are merits in explaining why these comparisons are instructive if scholarship and reporting on Sanseito’s impact is to be more than a post-mortem.

The growing role of falsity and untruths in politics is a topic that I have been increasingly called upon to raise in lectures to my university students. When so doing, I often provide them the template for action given by the French historian and Holocaust survivor Pierre Vidal-Naquet, when he wrote about his struggles against Holocaust deniers in 1980s France: “But how to respond since discussion is impossible? By proceeding as one might with a sophist, that is, with a man who seems like a speaker of truths, and whose arguments must be dismantled piece by piece in order to demonstrate their fallaciousness. And by also attempting to elevate the debate, by showing that the revisionist fraud is not the only one to adorn contemporary culture, and that not merely the how but also the why of its lie needs to be understood.”

The impact of Sanseito’s shifting political discourse within Japan and its cynical stance toward the public sphere will be felt far beyond its electoral gains. Rather than missing the forest for the trees, it’s incumbent on the media, politicians, and intellectuals to illustrate the larger context, impact, and patterns of lies. This is not a matter of partisan politics or knee-jerk reactions, but a question of either abiding by, or abandoning, the norms of liberal democracy.

Dylan O’Brien is an anthropologist whose research examines how cultural and religious differences are debated and understood in contemporary Japan. He has carried out multiple years of fieldwork with Jewish organizations in Tokyo and Kansai, and previously, organic health lifestyle communities across Japan. He completed his PhD at the University of California, San Diego, and teaches at several universities in Tokyo.