Issue:

August 2025

Geoffrey Tudor, former JAL PR supremo and much-loved member of the Club, has released a collection of his columns

Foreign tourism in Japan has undergone a revolution over the last dozen years. Once an exotic travel destination for a tiny global elite, Japan attracted a record 21.51 million foreign visitors in the first half of this year. Their spending is now Japan’s second-biggest source of export revenue after automobiles. Industries of Japan Inc. that held the rest of the world in awe – semiconductors, machinery and consumer electronics – have been supplanted in monetary value by hordes of foreign sightseers, posing for Instagram in front of Mount Fuji and the maiko of Gion, or jostling for snacks in the Nakamise of Asakusa.

Economists will tell you this gaijin tsunami is a consequence of currency depreciation. Since January 2013, the yen has fallen by 75% against the U.S. dollar as the Bank of Japan opened the monetary sluice gates. From being the most expensive member of the G7 to visit, Japan is now one of the most affordable. It is also true that citizens of South Korea, mainland China and Taiwan, which account for the bulk of inbound travel, are far more affluent than in the days when Japan led developing Asia’s “flock of geese”, and frustrated American autoworkers smashed Japanese cars with sledgehammers.

The dismal science does not explain everything. What foreigners chiefly want to see and experience in Japan today is much the same as what intrepid European and American visitors waxed on about when Japan was opening to the world more than a century-and-a-half ago – a country of astonishing natural beauty that managed to preserve much of its unique culture while hurtling down the track of Western-style modernization.

The Englishman whom Japan Airlines chose as its manager for international PR grasped this intuitively. “I came to understand that Geoffrey Tudor’s purpose during his 38-year JAL career went far beyond promoting the airline itself and its transportation services. His real client was vastly larger: Japan and its marvellous culture,” Bradley Martin, a close friend of Tudor and former Tokyo bureau chief of Newsweek, notes in an introduction to Tokyo Diary, a sampling of Tudor’s voluminous writings for JAL between 1975 and 2021.

From over 500 columns that he penned for JAL publications aimed at its non-Japanese employees, Tudor has selected 175 for this book. Many concern customs, cuisine and etiquette that he observes in daily life, especially Japan’s renowned celebration of changing seasons.

Japan’s pre-modern history is a particular fascination. Friends will recall Tudor’s championing of Will Adams, aka Miura Anjin, the shipwrecked English navigator who become a samurai advisor to Tokugawa Ieyasu. Centuries later, it is easy to see how the story appealed to another imaginative and enterprising Englishman who finds himself in Tokyo, once again trying to bridge an age-old cultural divide.

On occasion, Tudor pursues his historical quarry with a doggedness worthy of Sherlock Holmes, another of his heroes. Not satisfied with the sleuthing of Japanese media into the origin of the sweet Japanese sponge cake kasutera (Castella), he pursues his own investigation of the cake shops of old Lisbon, and makes a surprising discovery ….

JAL encouraged Tudor to cultivate the foreign press in Japan, but his devotion to the FCCJ went far beyond the call of duty, and in recognition of years of committee service he was eventually made a life member.

In the company of often raucous journalists, Tudor came across as mysteriously calm and detached, prompting curious onlookers to try and decipher his quizzical expressions, be it the twitch of a carefully trimmed moustache or the arching of an eyebrow. Hugh Sandeman, a former Tokyo correspondent of the Economist, perfectly captures the Tudor manner in another foreword to Tokyo Diary:

“Geoff had the same piece of clear but startling advice he gave when I first met him: ‘Just listen’. A sobering thought for the many of us who had thought that opinions were like weapons at gunfights: to be drawn and fired off without any pause for thought. I learned a lot from Geoff’s ability to listen out the gunfight with a look of light amusement. Followed by a carefully aimed comment at whoever was left standing.”

Tudor grew up in Norwich, a provincial English city famous for its Norman cathedral, pungent yellow mustard and TV comedy character Alan Partridge, who made a star out of actor Steve Coogan.

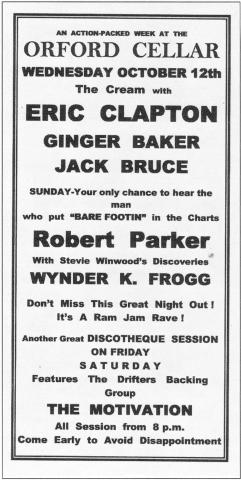

One of Tudor’s varied jobs after leaving school in 1962 was at the Orford Cellar, a Norwich music venue underneath the Orford Arms pub, where he worked as MC, receptionist, ticket collector, barman and doorman. The Cellar started as a jazz club but later switched to rock and roll and R&B. Among those who played in eastern England’s answer to Liverpool’s Cavern Club were Rod Stewart, Cream (Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce), Jeff Beck, Long John Baldry and Jimi Hendrix. Rod Stewart, a lifelong fan of model railways, would bring handmade models of rolling stock backstage. Tudor also recalls once going on stage to request Hendrix play his guitar with his teeth. (Decades later, such stage management skills were invaluable when Tudor organised the FCCJ’s 40th anniversary party, attended by Crown Prince Akihito and Crown Princess Michiko.)

At the end of the Sixties, Tudor joined JAL in London as PR and advertising manager for the UK. In 1974 he was hired for a new role in Tokyo heading a JAL magazine, but the post vapourised amid corporate belt-tightening in the wake of the first oil shock. As his transfer had already been agreed, he nevertheless found himself “standing by an island of empty desks on the 9th floor of the Tokyo Building in Marunouchi, the corporate headquarters of Japan’s national carrier”. Thankfully, the desks soon began to fill, as did Tudor’s responsibilities.

His columns in Tokyo Diary for the most part eschewed the news cordite that often filled the main bar of the FCCJ, but Tudor never ducked for shelter when calamity came to his employer.

In 1982, the president of JAL, still part-owned by the government, narrowly dodged strong calls for him to quit after an undiagnosed schizophrenic pilot caused a DC-8 to crash in Tokyo Bay on its approach to Haneda, with the loss of 24 lives.

The acute embarrassment caused by this misfortune was nothing compared to an appalling tragedy three years later, when a Boeing 747 crashed into a steep, densely wooded mountain range northwest of Tokyo. JAL Flight 123 was packed with parents and children travelling from Tokyo to Osaka for the August o-bon festival. Thirteen minutes after take-off the Jumbo began to swerve wildly off course and the pilot issued a distress call. Half an hour later the plane disappeared from radar screens. All but four of the 524 passengers and crew were killed in what remains the world’s worst single aircraft disaster.

The cause of the crash was a sudden rupturing of the aft pressure bulkhead. JAL and Boeing jousted over responsibility, with Tudor strongly denying Boeing accusations of improper JAL maintenance. It was finally determined that Boeing engineers had botched a bulkhead repair after the 747 made a “bounced” landing at Osaka in 1978 and dragged its tail along the tarmac.

Tudor’s help was indispensable to an investigative feature that I wrote for the Observer, complete with a dramatic graphic based on a time-annotated chart of Flight 123’s flight path that he gave me.

Boeing was deemed culpable for the structural failure and explosive decompression that led to the crash, yet many more lives could probably have been saved had it not been for bungling and infighting among Japanese emergency services. It took almost 10 hours after the plane had slammed into Mount Osutaka for a Japanese air force helicopter to pinpoint the exact location.

In lighter vein, Tudor invited me to join a joyous JAL press junket to Hokkaido. Besides a luminous vision of a snowcapped volcano near the Niseko resort, what sticks in my memory is my first time on a piste. I had previously only skied on water, never on the white stuff. Tudor and Richard Hanson opted to watch our group from the upstairs bar of JAL’s hotel at Niseko. “Wow! Look at that guy go! He’s really flying down!” Hanson exclaimed, to which Tudor drily replied, “Yes, it’s McGill, and he doesn’t know how to stop.” True, and I narrowly missed a tree. Fittingly, the entertainment on the bus ride back to Sapporo was BBC videos of Mr. Bean.

I am also grateful to Tudor for showing me the inside of an active volcano. In 1996, we entered a 500-meter-long tunnel bored into the side of Sakurajima, the mighty cone that dominates the skyline of Kagoshima. Sensitive equipment at the end of the tunnel helps in predicting when Sakurajima will next belch clouds of ash into the air, essential knowledge for pilots approaching or taking off from JAL’s Kagoshima Airport. My name does not appear, but “Under the Volcano” is another Tudor column in Tokyo Diary.

The book is self-published, and copies have been given to his many friends at the FCCJ. The end page carries a touching note of self-deprecation. It reads, “To my parents: I finally finished something ….”

For several years, Geoffrey Tudor has suffered from Parkinson’s disease, and he now resides at a nursing home in Kunitachi, western Tokyo. He welcomes correspondence. The address is Geoffrey Tudor, c/o PD House Kunitachi, 5878-9 Yaho, Kunitachi-shi, Tokyo 186-0011, Japan

Peter McGill was FCCJ president from 1990 to 1991, the youngest in the history of the club.