Issue:

August 2025 | Cover story

Japan’s use of the death penalty makes it a criminal justice outlier. Why does the state continue to kill its citizens?

The execution of Takahiro Shiraishi, carried out on June 27 at the Tokyo Detention Center, came as a surprise—not because the sentence was unexpected, but because such secrecy is standard practice in Japan. Prisoners typically receive only minimal notice, often just a short time before the sentence is carried out. The warning is so brief that executions are kept entirely secret until after they have taken place. When asked for comment, Shiraishi's attorney told local television he was so stunned that he “could not even think of a response”.

Shiraishi, widely known as the “Twitter killer,” was convicted in 2020 for the murders three years earlier of nine individuals – eight of them women – and dismembering their bodies. At the time, the 27-year-old was employed as a scout, recruiting women to work in the sex industry in Tokyo’s Kabukicho district. Using Twitter, he targeted vulnerable young people who had expressed suicidal thoughts, luring them to his apartment south of Tokyo under the false pretense of helping them end their lives. The sheer brutality of his actions stunned the nation, standing out even in a society that has witnessed other notorious acts of violence.

The execution by hanging also ended a prolonged hiatus that had fueled speculation about a possible move toward abolition. That shift, however, did not materialize. Few in Japan felt compassion for Shiraishi on the day his execution was announced. Still, the recent domestic debate, coupled with mounting international criticism, may in time leave a lasting imprint on the national discourse surrounding capital punishment.

Owing to the large number of death row inmates it holds, the Tokyo Detention House is Japan’s most active execution site. Additional execution chambers are located at detention centers in Osaka, Nagoya, Fukuoka, Hiroshima, Sendai, and Sapporo. As of 28 June 2025, a total of 105 inmates remain on death row across Japan, awaiting execution.

Source: Wikimedia Common; Photo: PekePon, 2008

Abolition gathers pace

Since the dawn of history, legal systems have emphasized punishment as a central pillar of social order. The most severe expression of this retributive framework was capital punishment, intended both as a form of vengeance against the offender and as a deterrent to potential wrongdoers. To reinforce these purposes, public executions were often staged as dramatic spectacles, drawing large crowds and leaving a deep and lasting impression on those who witnessed them.

In recent decades, this kind of spectacle has become increasingly rare. Since World War II, the rise of human rights norms, growing concerns over wrongful convictions, the lack of clear deterrent effect, and a gradual shift in public opinion have led many countries to abolish capital punishment altogether or cease using it in practice. In the UK, for example, the last execution took place 61 years ago, and the death penalty was formally abolished in 1998. In France, the process began somewhat later: the last execution occurred 48 years ago, legal abolition followed four years later, and in 2007 it was constitutionally banned “under all circumstances”.

As of 2024, some 144 countries, representing over 70% of United Nations member states, had either abolished the death penalty in law or refrained from carrying out executions for at least a decade. Nonetheless, international law does not impose an absolute ban on its use. Even among the 38 OECD member countries, let alone the seven members of the G7, two countries regularly carry out executions: the U.S. and Japan. In the U.S., the picture is complex. While 23 states have abolished the death penalty, only 16 of the remaining states have conducted executions over the past two decades. In the last five years, that number drops further – only 12 states carried out executions, representing fewer than a quarter of all U.S. states.

Japan, in contrast, retains the death penalty nationwide and has enforced it with increasing regularity in recent years. Since the start of the 21st century, 99 people have been executed – two of them women – an average of about four per year, more than twice the rate observed during the final quarter of the 20th century.

In terms of number of executions, 2018 was exceptional even by Japanese standards. That year, no fewer than 15 individuals were put to death, placing Japan eighth on the troubling global list of 20 countries actively applying the death penalty at the time. With the exception of the U.S. – ranked seventh with 25 executions – all countries positioned above Japan are, to say the least, not renowned for their commitment to human rights: Egypt (43), Iraq (at least 52), Vietnam (at least 85), Saudi Arabia (149), Iran (at least 253), and China, which topped the list with more than 1,000 executions annually.

A closer look at this ranking reveals two distinct clusters, in which the U.S. is something of an anomaly. The first includes at least 20 Muslim-majority countries that either fully or partially implement Sharia in criminal law or apply it as the basis for personal status legislation. The second cluster comprises countries that are or were historically influenced by the Chinese imperial tradition. These countries largely adopted its legalist conception of governance, along with the social and moral framework known in the West as Confucianism. Beyond mainland China itself, this group currently includes Taiwan, which resumed executions this January after a five-year hiatus, Vietnam, Singapore, North Korea, and, to a lesser extent, South Korea, which still retains the death penalty in law. Notably, Japan also belongs to this cluster.

Although these countries have undertaken significant legal reforms – Japan beginning in the late 19th Century – they all share a common legacy. This legacy, characterized by centralized authority that prioritizes hierarchy and state control over individual rights, operates with limited transparency, and fosters a model of citizenship grounded in obedience and deference to state power. Such historical foundations may help explain the enduring and widespread public support for capital punishment observed in these societies today.

Alongside this cultural context, it is important to emphasize that the record year of 2018 did not mark a fundamental shift in Japan’s penal policy. Of the 15 individuals executed that year, 13 were members of the Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult who had planned or actively participated in the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway 23 years earlier. That attack killed 14 people, and the cult's overall activities ultimately resulted in a total of 29 deaths. This large-scale, coordinated execution was highly uncharacteristic of the postwar Japanese system, which reserves capital punishment for a narrow category of “particularly serious crimes” typically committed by a single offender. These usually involve aggravated murder, most often with multiple victims, accounting for 92% of the cases in the 21st century, and especially in instances of serial killings or when the offender was on parole for a pervious homicide.

Japan Ground Self-Defense Force personnel decontaminate subway cars affected by sarin gas on 20 March 1995, following the Tokyo subway attack that killed 14 people and injured over a thousand. In the years that followed, 189 members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult were indicted for their involvement in the attack. Among them, 13 were executed in 2018.

Source: Wikimedia Common

International criticism

The most prominent organization in the campaign against capital punishment in Japan and globally is Amnesty International. Founded in London in 1961, the organization advocates for human rights worldwide and identified early on the gap between Japan’s humanitarian image and its legal reality. As early as 1983, it called for the abolition of the death penalty in Japan. Over the years, Amnesty has issued strong and consistent criticism of Japan’s treatment of death row inmates, particularly the practice of holding them for extended periods. While the average wait before execution is around seven years, there have been notable cases where prisoners were executed more than two decades after being sentenced. A striking example of Japan’s system is the case of the Aum Shinrikyo members. Indictments were filed in the summer of 1995, and the trial – including an appeal to the Supreme Court – concluded in 2006. Yet their execution was delayed another 12 years, underscoring the protracted and opaque nature of Japan’s capital punishment process. Admittedly, the situation in the United States is even more extreme: in 2022, the average time spent on death row for those executed reached 20.2 years, up from six years in 1984 and already exceeding 15 years by the early 2000s.

Another major source of criticism concerns both the timing of execution notifications and the conditions of confinement. Inmates on death row in Japan are typically informed of their execution only shortly before it is carried out – sometimes just one or two hours in advance. Until that moment, they are held in small cells under conditions of prolonged solitary confinement, subjected to a rigid daily regimen, and denied even the basic right to speak freely. Amnesty International, which opposes all forms of capital punishment as a matter of principle, stated in a 2009 report that such practices were particularly cruel and may “push prisoners to the brink of mental illness”.

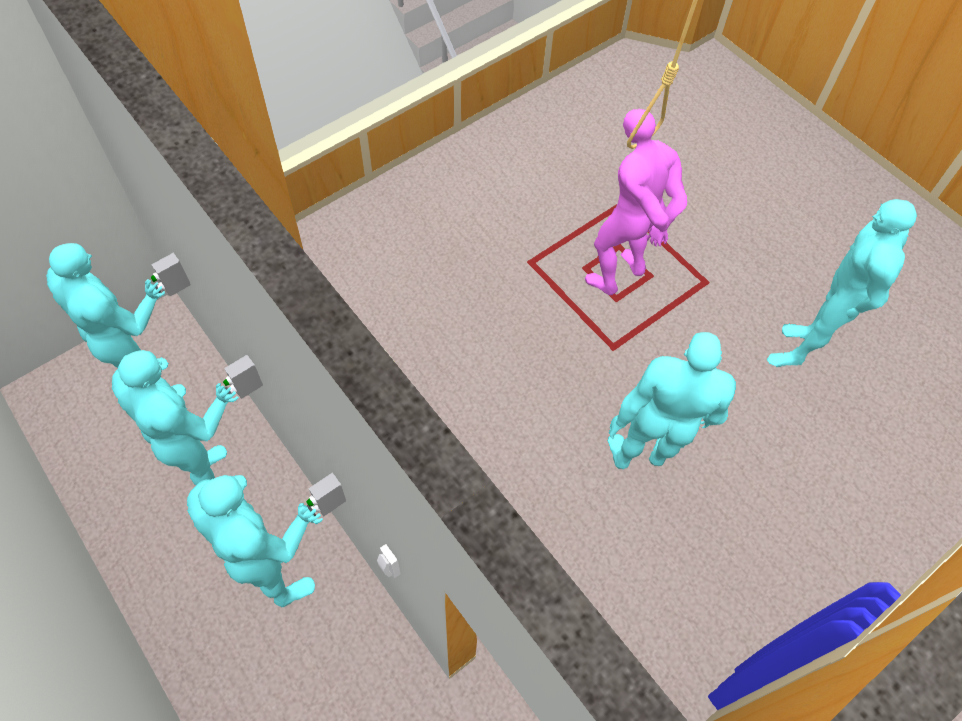

A schematic depiction of Japan’s method of execution by hanging: The condemned prisoner is escorted into a specially designated chamber and positioned on a trapdoor platform with a noose placed around the neck. Three officers, whose identities remain undisclosed, press buttons simultaneously—only one of which activates the trapdoor—ensuring that no individual knows who triggered the mechanism. The floor opens beneath the prisoner, resulting in death by hanging.

Source: Wikimedia Common; Design: Asanagi, 2024

Despite mounting criticism, Japan’s law enforcement authorities continue to defend the practice of late execution notifications, arguing that it helps prevent suicides among death row inmates. In recent years, the system has demonstrated only limited openness, primarily on peripheral matters – for instance, permitting the use of air conditioners in prisons or instructing guards to address inmates with the respectful suffix “-san.” However, it has largely avoided addressing the core issues related to the confinement of death row prisoners. Most notably, in April 2024, the Osaka District Court rejected a lawsuit filed by two inmates challenging the late-notification practice and dismissed their claim for compensation for the psychological distress it caused.

The factors influencing the final decision to carry out capital punishment in Japan also warrant close attention. In the case of the Aum Shinrikyo members, as with all death row inmates, the ultimate decision to authorize the execution of the cult members – after a prolonged delay – lay solely with the justice minister. After a prolonged delay, it was then-Justice Minister Yoko Kamikawa who approved the executions of the cult members. Our analysis of the executions over the past 30 years highlights stark differences among justice ministers in their readiness to sign execution orders: some refrain entirely, while others readily authorized them. Among all, the soft-spoken and composed Kamikawa has signed off on more executions than any of her predecessors, with no fewer than 16 carried out during her tenure. She is followed by Kunio Hatoyama with 13 executions, and Jinen Nagase and Sadakazu Tanigaki with 10 each. A search for commonalities among the four reveals that they all belong to the same political party and are graduates of the University of Tokyo. Notably, three of them earned their degrees in its Faculty of Law, placing them squarely at the heart of the Japanese establishment.

Even more striking is the fact that all of these justice ministers were appointed by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, and, with the sole exception of Kunio Hatoyama, the executions they authorized took place during Abe’s two terms in office. This pattern suggests more than mere coincidence, especially when viewed alongside statistical trends that point to a significant divergence between Abe and most other prime ministers. During Abe’s first term, which lasted only one year, 10 executions were carried out. In his second, nearly eight-year term, another 36 took place. By contrast, in the nearly five years since Abe’s 2020 resignation, only five executions have been conducted – an annual rate five times lower than during Abe’s tenure.

Abe’s appointments and the corresponding execution figures underscore his substantial influence over Japan’s criminal justice policy, particularly through the formation of a cabinet aligned with his broader ideological vision. Under his long and stable leadership, Japan gradually moved toward a more centralized and conservative policy direction, reversing many of the liberal reforms and values that had gained traction in earlier decades. His administration prioritized law and order, national security, and traditional societal norms, fostering a political climate in which capital punishment not only endured but was implemented with increasing regularity.

During her first two tenures as justice minister—lasting less than 26 months and both under Prime Minister Shinzō Abe (left)—Yōko Kamikawa (right) authorized the execution of no fewer than 16 death row inmates. In contrast, some justice ministers completed their entire term without signing a single death warrant.

Source: Wikimedia Common; Photo: Cabinet Public Relations Office, Cabinet Secretariat

Although individual personalities certainly play a role in shaping policy, Abe and his justice ministers were far from alone in supporting the continued use of capital punishment. Japan’s conservative leadership and institutional framework have long upheld its legitimacy and resisted efforts toward abolition. Even during the brief tenure of the Democratic Party (2009–2012), no serious attempt was made to repeal the death penalty. The Ministry of Justice continues to justify its retention by appealing to concerns over public safety and the interests of victims’ families, frequently citing high levels of public support as evidence. Yet the dynamic between state and society remains ambiguous: is the government simply responding to popular sentiment, or is it actively shaping public attitudes through its messaging and policy choices?

While this question is important, a deeper inquiry may be needed to understand why both the political establishment and the public remain steadfast in their support for capital punishment, despite global trends and mounting international criticism. Politically, successive prime ministers and LDP-led cabinets have faced virtually no electoral consequences for maintaining the death penalty. In contrast to Western Europe or many U.S. states, Japan lacks a significant ruling-party faction advocating for abolition. In November 2024, a 16-member public advisory panel recommended greater transparency and national discussion on the issue, but the cabinet quickly and unequivocally rejected any move toward abolition.

Culturally, many proponents of the death penalty appeal to a deeply rooted belief in “atonement through death”. According to this view, certain crimes—particularly multiple or especially heinous murders—demand the ultimate form of retribution. This sentiment is regularly echoed in media coverage and by victims’ families, who often frame execution not merely as justice but as a moral necessity and a form of emotional closure. Such beliefs continue to shape the discourse in a society where notions of shame, repentance, and societal harmony retain powerful cultural resonance.

Finally, the Japanese public tends to view capital punishment as an effective deterrent. Its rare and calculated application—particularly in high-profile, exceptionally gruesome cases or serial killings—is perceived as the ultimate punitive measure within a legal system that, by international standards, is relatively successful in preventing crime. But does it truly deter? Despite enduring public support, empirical evidence suggests otherwise. Several Japanese studies have found no indication that the death penalty significantly reduces serious crime. In fact, researchers have consistently failed to establish a clear deterrent effect linked to either death sentences or executions Research by Mori (2020) and Muramatsu et al. (2017), using statistical models and homicide data from 1990 to 2010, concluded that neither the frequency of death sentences nor executions correlated with lower murder rates. In contrast, legal reforms such as longer prison terms demonstrated measurable deterrent effects. Notably, even the Ministry of Justice has acknowledged the absence of scientific proof for deterrence.

Signs of change?

These research findings, along with mounting criticism both domestically and internationally, are not without effect. Although governmental and public support for the death penalty in Japan has long appeared unwavering, it may not be immutable. Over the past 12 months, the country’s criminal justice system has exhibited clear signs of increased flexibility. Most recently, on June 1, the government enacted the most significant changes to the criminal law since 1907, redefining the mission of correctional institutions from a focus on punishment to an emphasis on rehabilitation. The reform is designed to address the rising rates of recidivism observed in recent years, despite a steady decline in overall crime. Under the new framework, convicted prisoners will be assigned to one of 24 distinct “correctional processes”, each tailored to the individual characteristics and rehabilitation needs of the inmate.

A second sign of change emerged last September, centered on the case of Iwao Hakamata, a frail 88-year-old man and the longest-serving death row inmate in Japan’s history. In 1968, Hakamata, a miso factory worker and former boxer, was convicted of murdering his employer, the employer’s wife, and their two children, all of whom had been stabbed to death. His conviction rested largely on a confession obtained during an extended interrogation conducted without legal representation, as well as traces of blood and gasoline found on his pajamas. For decades, Hakamata insisted that his confession had been coerced and that he was innocent.

In 1980, the Supreme Court rejected his appeal, but Hakamata continued to fight to prove his innocence from death row, where he remained for nearly 50 years. In 2014, following the discovery of new evidence, including DNA tests and the concealment of key findings by the police, the Shizuoka District Court ordered a retrial and decided to release Hakamata from prison. Although this decision was overturned four years later, Hakamata persisted in his struggle. In 2023, a renewed examination of the case concluded that his confession was unreliable, prompting the court to order another retrial. Finally, in September 2024, the court ruled that his conviction had been based on deeply flawed procedures, and the state was ordered to pay 200 million yen ($1.4 million) in compensation.

The full acquittal of Hakamata reignited a heated public debate on capital punishment, coerced confessions, and “justice delayed”. But did the acquittal influence public opinion? Since 1994, the Japanese government has conducted a comprehensive public opinion survey on the death penalty every five years. These surveys consistently show that about 80% of respondents support capital punishment “in certain cases”. These findings are echoed in international surveys as well. A global poll conducted in 2021 across 55 countries found that 74% of Japanese respondents supported the death penalty—an identical rate to that in South Korea and higher than in any other country surveyed, including the United States (67%).

The September 2024 acquittal of 88-year-old Iwao Hakamata drew national attention and public emotion, yet it failed to shift public opinion on the death penalty.

Source: Wikimedia Common

The latest round of the government’s death penalty survey was conducted in November–December 2024, shortly after Hakamata’s acquittal was announced. Given the timing, opponents of capital punishment hoped the results would reflect a significant drop in public support. To everyone’s surprise, the opposite occurred. The findings, published in March this year, revealed that support for capital punishment had actually risen to 83.1%, an increase of 2.3 points from the previous survey.

The Japanese public, then, appears largely unmoved even by Hakamata’s extraordinary acquittal, let alone by longstanding criticism from organizations such as Amnesty International. A broad consensus still seems to prevail in Japan that the country’s low crime rate and impressive public order – which often draw admiration from foreign visitors – are due in part to the firm and uncompromising stance of the legal establishment. It is still commonly argued that the system’s overall deterrent effect justifies occasional miscarriages of justice, and that such errors do not warrant a fundamental reassessment of the legitimacy of the entire system.

The recent execution of Shiraishi, the first in 35 months, provides further evidence of the consistency of Japan’s policy on capital punishment and arguably signals a step backward. In this sense, both the legal system and prevailing public sentiment in contemporary Japan continue to reflect the enduring legacy of the authoritarian legal traditions and Confucian thought that have long shaped the Sinosphere. It is not coincidence that, in an era marked by rising social alienation, terrorism, political instability, and populism, this model may hold appeal to broad segments of society, even in countries that currently refrain from using capital punishment.

Nonetheless, critics of this punishment, or at least the way it is implemented, are unlikely to abandon hope. After all, over the past 150 years, domestic advocacy and international criticism have played a vital role in encouraging Japan to adopt more humane legal reforms and to emerge, in many respects, as one of the world’s most enlightened and progressive nations.

Rotem Kowner is a historian and professor of Japanese Studies at the University of Haifa, Israel. His book How Yellow Became Inferior: The Japanese and the Dynamics of Racial Thought, 1735–1854 (McGill-Queen’s University Press) is forthcoming.