Issue:

December 2021

The horror of biological warfare: visiting the Unit 731 museum in Pingfang, China

"Nu-huh. You. Get off here." The unsmiling female bus driver barked her orders and gestured toward the exit. Then she stopped me and demanded a 1 yuan surcharge, as I had ridden beyond the sector covered by the basic fare. I paid.

It was just past noon on September 20, 2018.

The bus had threaded its way from the central part of Harbin, in China’s Heilongjiang Province, to the suburbs, rattling along rural, tree-lined roads for about three quarters of an hour to the district of Pingfang, which means "flat house" in Mandarin Chinese.

Disembarking, I found myself on a dusty commercial street that could have been in any town in China. My destination was not in sight, and I had no map. But I was confident. Surely a site as famous as the Museum of War Crime Evidence by the Japanese Army Unit 731 would be known to the locals.

I approached several men squatting on the sidewalk discussing how to repair a motorcycle engine and, with a polite "Qing wen," politely asked directions.

"Turn left at the next corner and walk straight ahead," one gestured with a grease-stained digit. "You'll see it across the road."

At the corner I spotted a sign for Budweiser beer over a bar entrance and photographed it for future reference.

Their directions put me directly across the wide boulevard from the museum, but a barrier prevented me from crossing the road. Instead, I was obliged to walk 300 meters to the next intersection, use the pedestrian crosswalk, then walk back 300 meters on the other side.

After photographing the museum's stark exterior with its sign in large Chinese characters, I walked down a ramp to the entrance. Admission to the museum, which was, at the time of my visit, only about three years old, was free of charge. To quote from the English brochure provided to visitors: "It ... records the complete process of the development, production and use of biological weapons as well as the preparation and implementation of biological warfare and human experimentation by Unit 731.

"It aims to inspire people to 'remember history, not forget the past, cherish peace and create the future.'"

The entire Pingfang army complex at one time covered some 250,000 square meters (62 acres), and while much of it today lies in ruins, a good part of what remains, while exposed to the elements, is accessible to visitors.

The Kwantung Army had moved to Pingfang from an earlier research facility nearby called the Zhongma Fortress. Starting from 1935, a unit deceptively named "Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army" set up shop, under the command of Lieutenant-general Shiro Ishii, a trained microbiologist, to engage in research into chemical, biological and other forms of asymmetrical warfare.

Between 3,000 and 10,000 prisoners, mostly Chinese and Russians, are believed to have died during experiments performed on them that included infection by pathogens, exposure to low temperatures and vivisection, to name a few. The toll of fatalities from biological warfare agents used in the field against enemy soldiers and civilians may have reached 400,000 or greater.

In echoes of campaigns against Holocaust denial in Europe, China seems to have anticipated that the work conducted at Pingfang would be downplayed, denied outright or overlooked as alliances shifted during the Cold War.

Along with actual laboratory implements such as microscopes, test tubes, beakers and other devices, the museum's exhibits include the baskets for breeding ground squirrels as carriers of the fleas to spread plague bacilli. Among the life-size three-dimensional exhibits are a blood-smeared table where vivisection experiments were conducted. Researchers, wearing gas masks and holding clipboards, observe the response of a woman and her child to a toxic gas. And a circle of men, bound to crucifixes, are subjected to explosions to measure the distances from which shrapnel would penetrate their clothing.

Along with the most visual exhibits, the museum displays documents as if presenting evidence at a trial, which in a sense it is. Exhibits include excerpts from verbatim eyewitness testimony and reproductions of actual documents, including those from American sources.

The Japanese scientists and military staff who worked at Pingfang are identified by name on wall panels. Some Unit 731 staff were tried and later served sentences in Soviet POW camps in Siberia and at Fushun prison, near Mukden. Most, including Shiro Ishii, had fled ahead of the invading Soviet forces and returned to Japan, where American occupation authorities allegedly exempted them from prosecution in exchange for their research data.

A panel by the exit reads: "The Unit 731 site is by far the largest historical site of biological warfare in world war history. It is also a historical witness to human suffering, a legacy and special memory of a brutal war. To combine two unique missions – preserving the historical site and uncovering the historical evidences – we bear the responsibilities of providing historical facts. With clear conscience, we are obliged to defend peace and prevent this tragic chapter of history from repeating itself."

As far as I could tell, no Japanese were present at the museum during either of my visits. However, while walking around the grounds I was accosted by a tall Chinese gentleman who addressed me in awkward, but comprehensible, Japanese. He appeared to be in his early or mid-60s, certainly too young to have lived in the former Manchukuo.

The man apparently was on the lookout for visitors and kept a book of written notes in Japanese. I made a few new entries and drilled him on their correct pronunciation.

One thing that puzzled me was, how could he have known I spoke Japanese? Was it just a stab in the dark, or was someone curious about my visit?

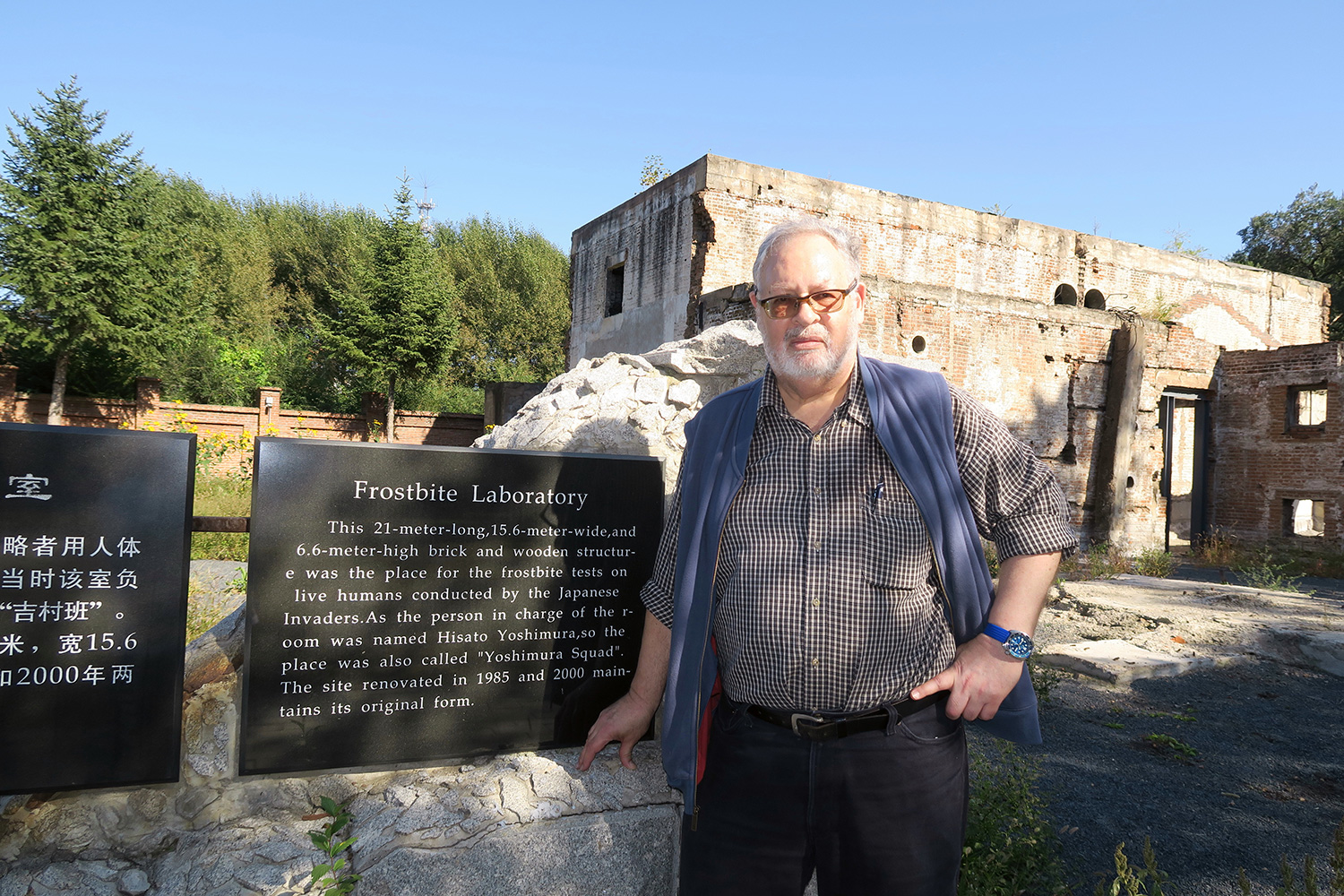

I certainly had nothing to hide, it was a lovely day and his company was welcome. He guided me to several spots, including an anti-aircraft gun, and willingly snapped photos of me standing in front of various signs and buildings, such as the frostbite research laboratory.

I bought two chilled drinks at a nearby store and we relaxed on an outdoor bench. Suitably refreshed, he then directed me to a separate section of the complex behind a row of apartment buildings that I would have almost certainly missed without a guide. Some of its buildings were roofless and damaged, their bricks carted off by locals for use as building materials.

Throughout our approximately two-hour encounter he didn't ask me a single personal question, which was also puzzling because as a general rule, Chinese tend to be intensely curious about foreigners, especially those who speak their language. Nor did he cue me to denounce Japan's wartime behavior. And he posed willingly for a photo.

Before we parted and I boarded the bus back to central Harbin, I insisted he accept a small gratuity, which he'd certainly earned as without his guidance I would have missed seeing an interesting part of the complex. Was my visit there reported to a government official? I have no idea, nor was I particularly concerned, since one must assume the local authorities could hardly object to a visiting tourist from one of China's wartime allies.

Sixteen months later, I happened to be back in China again to attend the Harbin International Snow and Ice Festival, and made a second trip to the museum with two American friends. The overcast sky with light falling snow and subzero temperatures made for a sharp contrast with the warm September day of 18 months earlier.

Between my first and second visits to Harbin, I also traveled to Fushun, a city about one hour from Shenyang (formerly Mukden). The now-empty Fushun War Criminals Management Center, open to the public as a museum, incarcerated some 1,300 accused war criminals, including Aisingioro Henry Puyi, the last emperor of China's Qing dynasty and from 1932 to 1945 the "puppet emperor" of Manchukuo. They included Japanese officers, police and others. By 1964 all had been repatriated to Japan and the prison closed in 1986.

Some three years after the war, the specter of Unit 731 may have resurfaced during the strange robbery of the Shiinamachi branch of the Teikoku (Imperial) Bank in Tokyo. Shortly after closing time on January 26, 1948, a man posing as a public health official persuaded 16 bank employees and the caretaker's family to voluntarily swallow "medicine" containing cyanide, and 12 died. The robber made off with ¥160,000 yen. Eight months later, an artist named Sadamichi Hirasawa was arrested and eventually confessed to the killings. Convicted and sentenced to death, he was never executed. The surviving witnesses described the killer as having a military bearing and possessing medical knowledge, characteristics that raised skepticism over artist Hirasawa's guilt. In May 1987, he died aged 95 in a prison hospital.

A "murder kit" closely resembling that used by the Teigin killer, according to the survivors' descriptions, is on display at the Noborito Peace Museum, located on the Ikuta campus of Meiji University in Kawasaki. The museum occupies a building once utilized as a laboratory for top-secret scientific research by an army unit with ties to Unit 731.

In 2020, the Noborito museum's curator, Akira Yamada, published a study based on police investigation data into the Teikoku Bank robbery that persuasively ties the poison method used by the Teigin killer to the Imperial Army.

Over the past several decades, materials concerning the activities of Unit 731 have continued to be published. In 1980, author Seiichi Morimura began a series in the Japan Communist Party newspaper Akahata that exposed Unit 731's atrocities. Titled Akuma no Hoshoku (The Devil's Gluttony), it was republished in two volumes in 1981 and 1982 by Kobunsha and reissued in 1983 by Kadokawa Shoten. Both Morimura and his publisher were denounced by rightist organizations for producing "propaganda novels".

Kyoto-based American writer Hal Gold (1929–2009) published several books in English on Unit 731. Japan's Infamous Unit 731: Firsthand Accounts of Japan's Wartime Human Experimentation Program is still in print and available in e-book format.

As much as I could glean from my two trips to Harbin, most of the visitors to the Unit 731 museum are student groups, starting with the youngest primary school pupils. Almost every major city in China seems to have a museum devoted to wartime atrocities committed by the Japanese military. The tone of their message is righteously indignant, but also phrased in a conciliatory manner towards those who acknowledged their crimes and repented. Still, one must wonder: if armed conflict were to break out in the western Pacific, would China regard Japan's wartime atrocities as justification for aggressive military action?

Mark Schreiber writes the Big in Japan and Bilingual columns for The Japan Times.