Issue:

December 2021

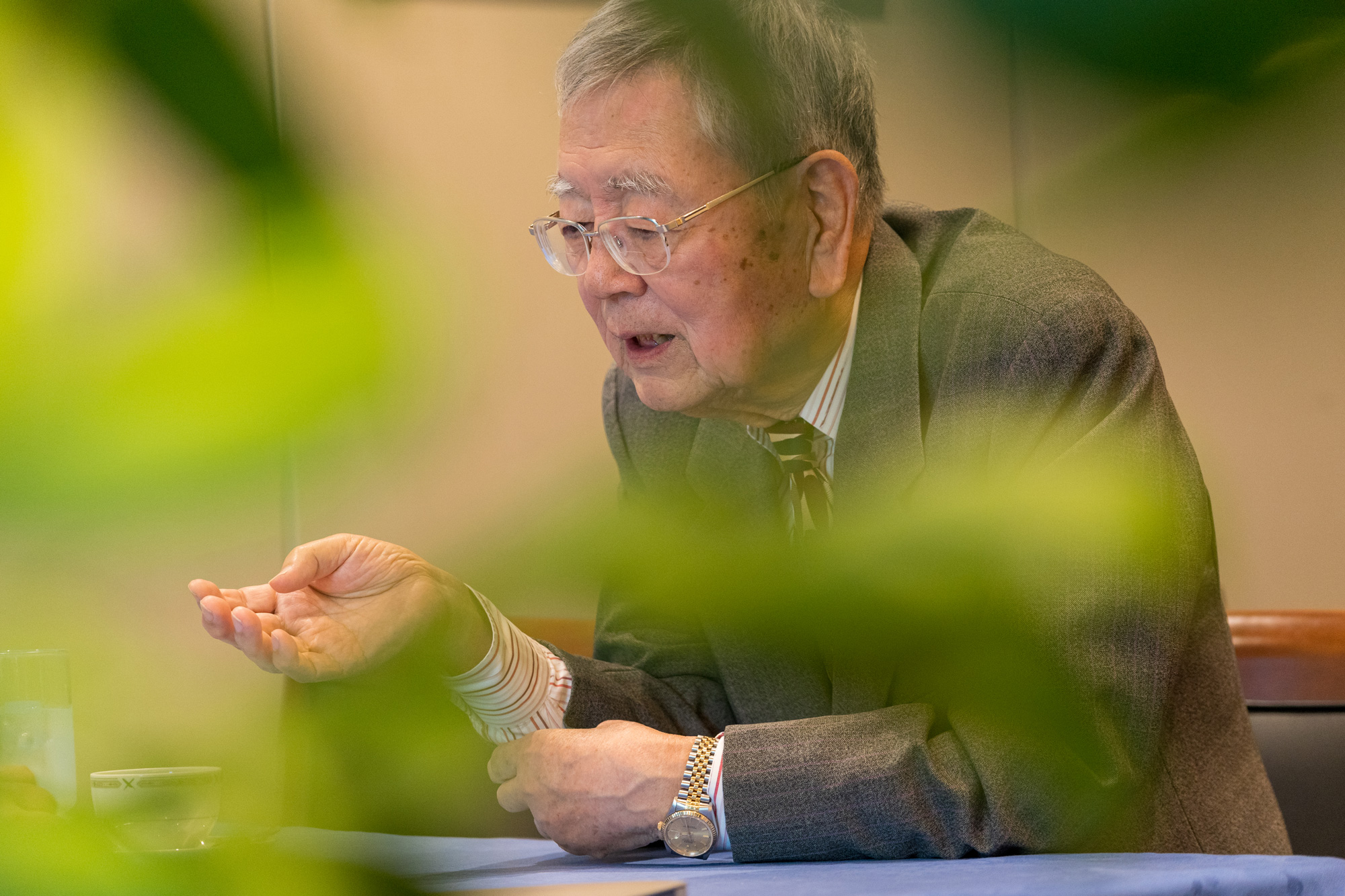

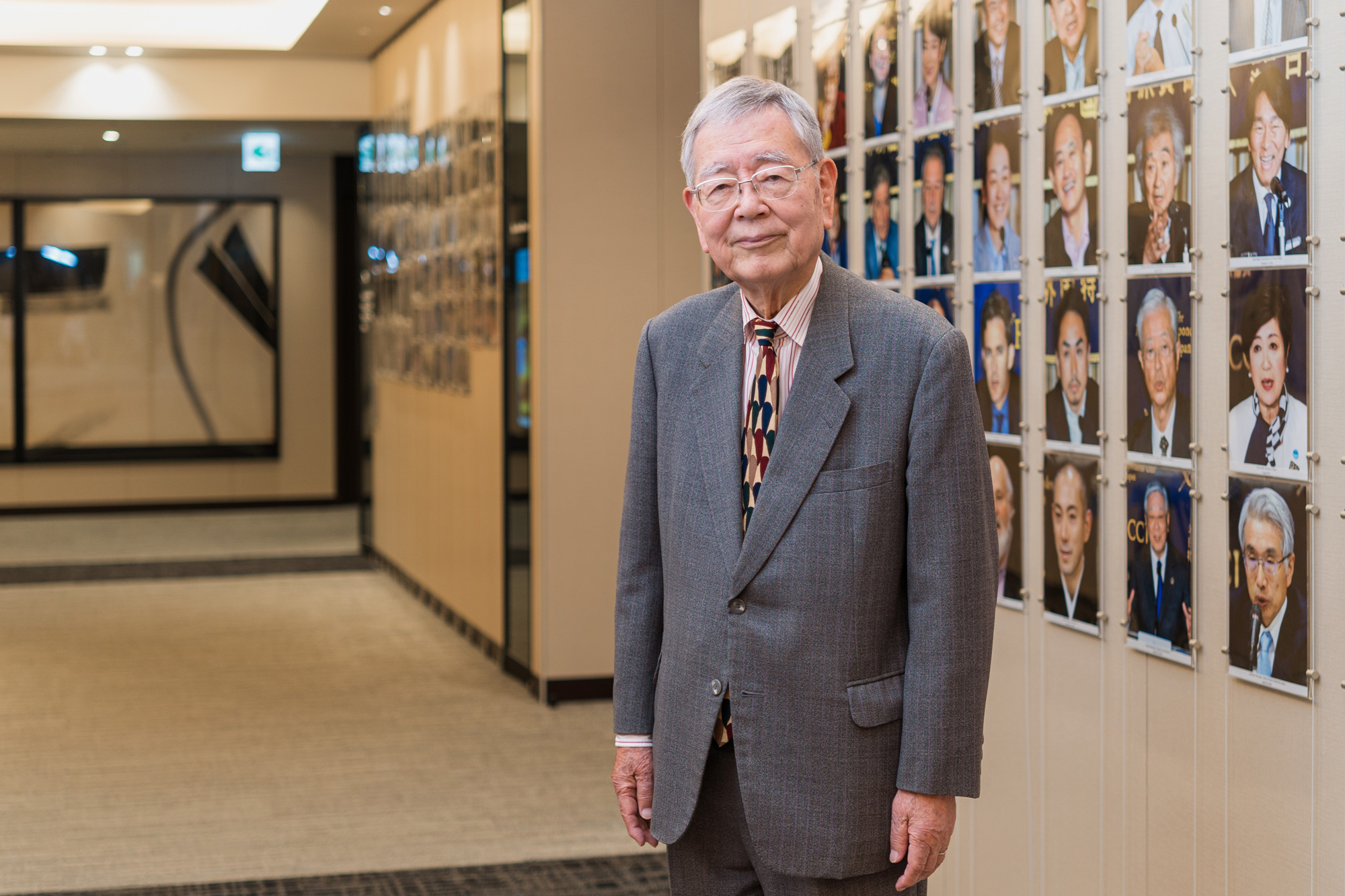

Kunio Hamada, former supreme court justice, has advice for the FCCJ and a warning to politicians hoping to rip up Japan’s postwar constitution

My recent meeting at the Club with former Supreme Court judge and longtime FCCJ member Kunio Hamada started as a regular interview but quickly turned into an experience that had me reflecting on my own career.

Hamada, 85, graduated in 1960 from the law department of Tokyo University along with his wife, Hanako, a high school classmate and one of only two women among department’s 600 students. In 1966, he received his LLM at Harvard University. He practiced in the field of international business transactions until 2001, when he was appointed as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. Hamada left the Supreme Court in 2006 at the compulsory retirement age of 70 and resumed his private practice. He does not support the death penalty, a stance that puts him at odds with government policy.

Hamada has been chairperson of the FCCJ Compliance Committee, an ad hoc body, for several years. Together with other regular and associate members, the committee has devoted a lot of time to overseeing the FCCJ’s adoption of public koeki status in 2014. Hamada continues to help the Club negotiate koeki regulations and help us find ways to reconcile our institutional role with our journalistic traditions.

More recently, Hamada has emerged as a critic of the conservative movement clamoring to change Japan’s postwar constitution. His articles and quotes appear regularly in the Japanese media, drawing on his legal expertise and determination to protect postwar democracy.

Before we discussed Club and constitutional affairs, Hamada was momentarily taken aback by his professional longevity. “Gosh,” he said, as he reflected on his career. “I didn’t realize that I have been working for more than half a century. How time flies!”

Question: You have written about your opposition to the former prime minister, Shinzo Abe, who has led the movement to rewrite the postwar constitution. Is it easy for a former judge to publicly oppose government policy?

Answer. It wasn’t my intention to take a leadership role in protecting Japan`s democratic constitution. Yet, sadly, I seem to be doing just that by holding politicians responsible for their constitutional transgressions. At a public hearing at the House of Councilors in 2015, I testified that Abe had clearly violated Article 9 of the Constitution in 2014 by adopting, as a cabinet decision, a national security policy allowing the Japan Self-Defense Forces top operate in foreign territories. In my articles, I also accused him of failing to convene an extra Diet session requested by the opposition in 2017. This is in contravention of Article 53, which clearly states minority political groups can order a debate. I have also pointed a finger at his successor, Yoshihide Suga, for refusing to do the same during his time in office. It is obvious that the postwar generation of politicians are not governing objectively. I am also upset because the judiciary has remained silent. (Opposition lawmakers have submitted lawsuits that are ongoing but the courts have not touched on whether the failure to call an extraordinary session was unconstitutional.

Q. What are Japan’s strengths as it confronts the huge changes now taking place in the world?

A. Japan became an economic power after World War II by developing a strong export industry. And that was partly thanks to the US government supporting Japan’s national security against the Cold War backdrop. But today, the political and economic challenges are different. The US is turning inward. Japan has to also find innovative ways to survive against influence of high technology led by the US and China. But there is a sense of crisis, as the nation’s leaders have not shown us the way forward.

Q. Can you explain your strong support for keeping the constitution as it is?

A. I believe that unless a majority of the Japanese people really opt for it, even a tiny change in the constitution must be prevented. Japan has lived peacefully with a strong economy since the end of the war, and any attempt to change this system to revive prewar social values that will destroy that democratic constitution. The Self-Defense Forces already have de facto legal recognition, and Japan has managed to govern adequately through its tradition of combining honne and tatemai – theory and practice. Why change that now?

Q. How do you view the FCCJ’s role in wider Japanese society?

A. As an organization that respects freedom of speech, the FCCJ is the only place in Japan where reporters can freely ask questions without holding back. And it hosts speakers from all walks of life. Bit it faces managerial challenges. Thanks to Japan’s commitment to free speech, Tokyo was a regional hub for foreign journalists. But geopolitics have changed, and the news is increasingly being made in China and other parts of Asia. This has adversely affected the FCCJ, so we need to come up with a plan of action to attract more journalist members.

Suvendrini Kakuchi is Tokyo correspondent for University World News in the UK.