Issue:

December 2021

Japanese YouTubers use English to highlight their country’s light and dark sides

It might be difficult to imagine an Englishman criticizing his home country on YouTube in Japanese. It would be even odder to encounter Japanese commenting on their country in English. For a start, the culture of criticism is somewhat rare in Japan and, secondly, not that many people speak English well enough. But YouTube videos Japanese people make in English are not for domestic consumption.

Shogo Yamaguchi (“Let’s ask Shogo – Your Japanese friend in Kyoto”), Chiba’s “Nobita” and Tokyo comedian “Meshida” came to YouTube from different angles, but all have found freedom to express opinions that many foreigners outside Japan don’t get to hear.

While Nobita (628,000 subscribers) initially set up a YouTube channel to practice his English, he quickly realized that people didn’t want to watch “rubbish videos” of a Japanese guy stumbling over a foreign language. So he resolved to up his game, both on the technical side and the content side. Initially, he hit the streets to interview people about dating and some of his videos started going viral.

“However, I wasn’t really interested in that, so I realized I really needed to change the topics,” he says. “And that’s when I started with more controversial topics, like social issues or politics.” Inevitably, this led to an attack of the trolls and now he’s less a man on a soapbox – he thinks Shinzo Abe is a centrist – and more an investigative reporter, finding out what other people think about issues. “Many people think I’m conservative, which is true on some topics but not everything, but I was always interested in social issues and I care about Japan.”

As his viewership rose to around 200,000 two years ago, Nobita scaled down his regular job in web production and scaled up YouTube. “That was a key moment for me,” he says. Now he spends four days a week on YouTube and three on other work.

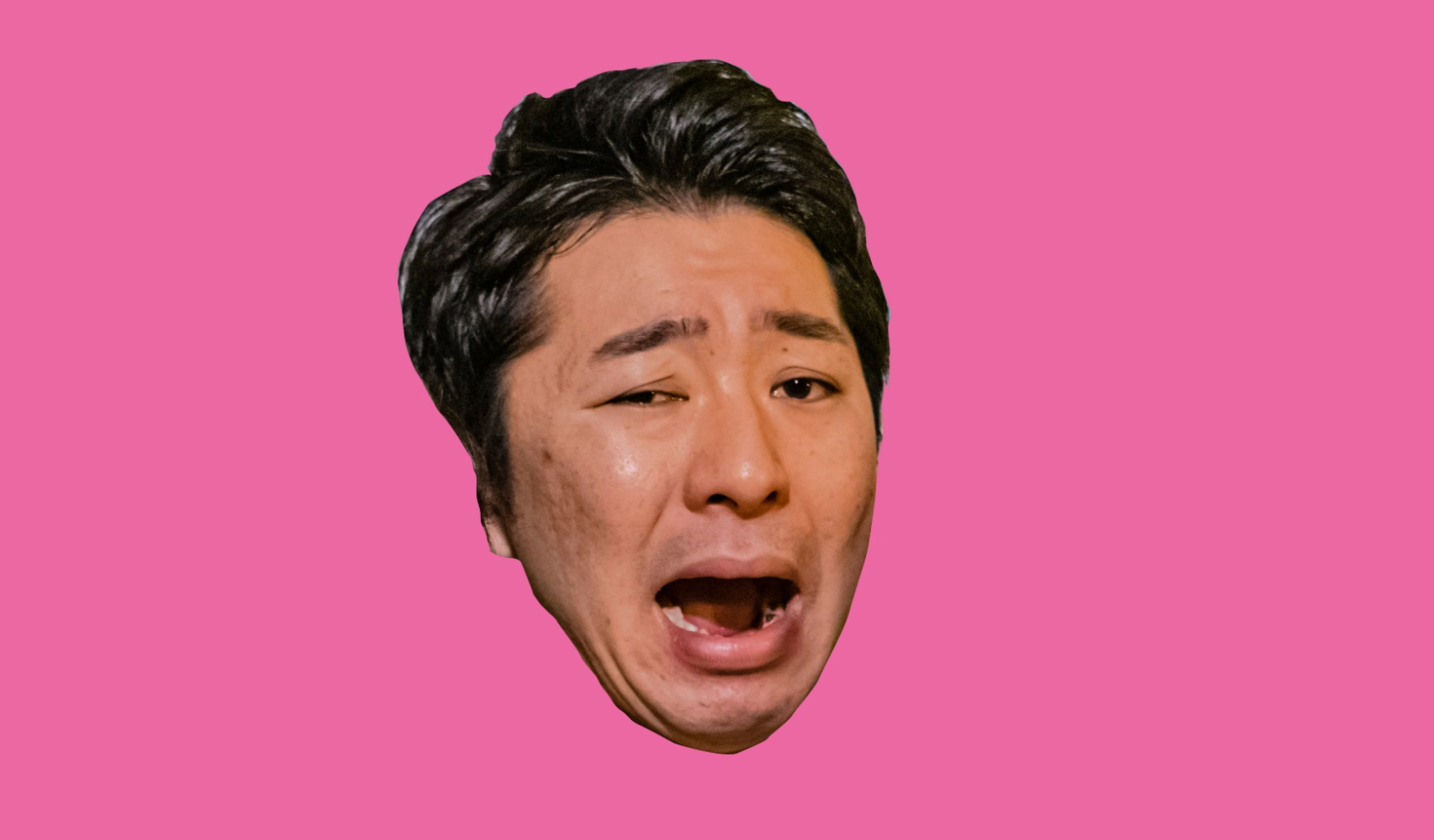

The YouTube channels of Nobita and Meshida have both used foreigners’ fascination with Japanese women as hooks to reel in viewers. But Meshida, 33, is trying to channel British comedians such as Ricky Gervais and Frankie Boyle to get his message across.

“Using Western humor, I want to make fun of Japanese culture or introduce Japanese culture,” he says. “I realized that even though I tried to make those kinds of videos, it’s difficult to get viewers because it’s already saturated with creators, so I needed a unique strategy. Just once, I uploaded a video with sexual content – introducing our sex industry – and only that video had good views, unfortunately.

“That became my strategy even though I actually wanted to be more like Trevor Noah and introduce Japanese news and my standup. But no one wanted to watch my standup; they were more interested in Japanese girls and Japanese porn, so, at first, I focused on the seedy side of Japan.”

With a big jump from fewer than 10,000 subscribers to over 70,000 in a matter of months, Meshida decided to try and broaden his range of topics and concentrate on explaining Japanese culture with comedy. “I really want to be a comedian, so YouTube is more of a tool to get fans and a community and advertise my shows. My main purpose is to make people laugh using Japanese stuff.”

Meshida sees Nobita as his benchmark for doing YouTube, along with “That Man Yuta” and “Shunchan.” “I really respect Nobita and his channel,” he says. “And I’m jealous because he has so many views and subscribers.”

Kyoto-based Shogo Yamaguchi used his love and experience of Japanese culture – swordsmanship, the tea ceremony, Noh – as a springboard into YouTube and he’s been spectacularly successful.

Having lived in Michigan for six years, his English is flawless (he also speaks Chinese) and his presentation skills are also a cut above the competition. After debuting on YouTube in July 2020, it took him five months to reach 1,000 subscribers. Three weeks later, he had 10,000 and three months later 100,000. He now has 328,000, having added 100,000 in the last two months.

Having worked in tourism, exposing Japanese culture to foreign visitors, he set up his own “experience” last year only to see it crash two months later because of Covid-19. “I wanted to continue pursuing something that I loved and talk about samurai and Japanese traditional culture in English, so that’s the reason I started with YouTube,” he says.

“The first video that boosted us up was a video where I talked about the difference between seppuku and harakiri,” Yamaguchi explains. “The day that I posted the seppuku/harakiri video was a day when a lot of people were searching about Mishima Yukio and his seppuku. It was just coincidence; I didn’t know about that at all.”

His most popular video is about on the pressure to be “normal” in Japan; he suffered a lot of bullying after returning from Michigan, something he has also documented, and he is keen to include social commentary alongside his videos on traditional Japanese culture.

“I am very afraid that in the future even for the people who are very interested in Japanese culture we won’t be able to provide such things, because who is going to be carrying on our culture? If we don’t solve our social problems, no matter how much we talk about traditional culture, there won’t be a proper society that will support the culture. You can’t enjoy culture in a society that’s corrupted.”

Unlike some YouTubers, Yamaguchi doesn’t feel obliged to present Japan in a good light. “I’m not trying to show Japan as something bad,; I’m trying to show the real parts about Japan. And the reason why is because I want to improve Japan and make it better. When you want to make something better, you have to look at what it’s really like.”

Which brings us back to the question of responsibility. Many YouTubers shy away from claims that they are pseudo-journalists, but, like Shogo, Nobita, are willing to rise to the challenge. “I’m trying to be a journalist rather than an entertainer,” he says. “I want people to start having conversations about things, which I hope will lead to making this country better.”

Fred Varcoe is a British freelance journalist. He was formerly sports editor of The Japan Times and Metropolis magazine, and has written on sports, music, cars and other topics for The Daily Telegraph, the Daily Mail, Billboard, Automobile Year, Reuters, the Japan Football Association, the International Volleyball Association and various websites.