Issue:

At a time when cartoonists are finding themselves a target of governments and extremists alike, Wang Liming is unabashedly poking the powers that be back home in Beijing.

When Chinese cartoonist Wang Liming arrived in Japan last May, he never imagined his first trip abroad would be his last. He’s now exiled in Japan, his new home. “I was planning to stay in Japan for about three months to meet with my business partner and explore the country with my fiancée,” he says. “But something very strange happened during that time.”

After he drew caricatures praising the kindness of the Japanese and the country’s pacifism, Wang’s Weibo microblogging accounts were terminated along with his Internet business. He was also denounced as a pro-Japan traitor and his life was threatened on a website connected to the official People’s Daily newspaper. “Now I’ll never go back, but will continue my work, feeling safer here.”

Wang, 41, first skirted the Chinese government line between cheeky cartoonist and defamatory activist in 2009 when he turned his pen to online political humor. It wasn’t until 2011, however, that he drew the obvious ire of authorities. Police in Hunan Province questioned him after he penned a cartoon that read, “One person, one vote to change China.” The officers told him there was freedom of speech in China, and they could not stop his work, but it was clear he was attracting some unwanted attention.

Warnings about his cartoons intensified after President Xi Jinping’s administration established new rules in 2013 prohibiting criticism of the Chinese communist party. Undeterred, he continued posting his satirical cartoons on sensitive topics including the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong and territorial disputes between China and Japan.

Then late one night in October that year, police in Beijing placed him in custody for almost 24 hours. He was charged with “suspicion of causing a disturbance.” Wang had posted a microblog about the lack of food and supplies delivered to the people who were stranded by flooding and literally starving in the eastern city of Yuyao. In response to the detention, Wang posted sketches of the small cell where he spent the night and other images depicting his treatment.

By 2014, his fame as the Biantai Lajiao (or “Rebel Pepper”) had gained him a million followers, but also made him a potential target for a dangerous smear campaign. “Before coming to Japan I was really debating whether I should continue drawing satirical cartoons. I didn't know what to do,” Wang admits. His Chinese business partner based in Japan recommended he stop, but his fiancée encouraged him not to give up. “There are many cartoonists in China but most give up as soon as they’re scolded by the authorities or threatened,” he says. “I can’t imagine my life without drawing political cartoons.”

Wang was born in the city of Tangshan in Heibei Province, about 180 km from Beijing. A precocious child, he had a passion for drawing as early as five years old. His parents, now retired teachers, encouraged him. He got his first taste of political satire in the 1980s thanks to the magazine Irony & Humor, and admits to being a lifelong fan of Japanese cartoonist Osamu Tezuka, the legendary creator of the manga and anime megahit series, Tetsuan Atomu.

When he made his fateful decision to stay in Japan last summer, he was faced with the frightening prospect of deportation if he overstayed his temporary visa. “I showed immigration officials that my life was being threatened in online postings, that it was too dangerous for me to return to China,” says Wang. He was hoping they would give him a special exception. But when they told him there was nothing they could do about his visa, he figured that he’d have to go back. But surprisingly enough, it was suggested that he apply for a longer-term, research-type visa. “I’m now a research fellow at Saitama University, thanks to an introduction by a Japanese journalist friend.”

Though his name has now been virtually wiped off the face of China-controlled Internet sites and Twitter, he’s not holding back on his opinions, thanks to his satirical cartoon wit. And because his works are no longer influential within China, concern for his family’s safety is no longer a large issue.

“I had no intention of becoming an enemy of the state. I started out drawing cartoons for my own interest without realizing they would influence so many people,” he says. “But the Chinese communist party has no sense of humor. They pretend they’re gods and can do no wrong. They’re like extremist Muslims who try to present a noble image.”

Wang says the conditions of freedom of speech in China have worsened since he left. “The arrests are different from before,” he says. “Before, they would first send people a letter of warning. Now there are no letters. People just disappear.”

He cites the well-known case of the poet Wang Zang, that spread like wildfire on Twitter: “He was arrested for his involvement with the Hong Kong protests and then tortured in prison. They made him stand for four days and nights and beat him so badly he had a heart attack. He was only 29 years old.”

“Even the Chinese assistant of a foreign journalist covering the Hong Kong protests was arrested,” he says, referring to Miao Zhang, who was assisting Angela Köckritz, a correspondent for the German weekly Die Zeit last October when she was arrested. She was charged with inciting a public disturbance and remains in prison.

When complimented for his bravery, however, Wang is self-effacing. “If I were really brave I’d go back to China. I’d continue to fight and willingly suffer the consequences,” he says. He cites the bravery of his friend, activist artist Ai Weiwei, who remains under house arrest in Beijing with police surveillance cameras mounted around his home and studio. “Actually, I was very frightened,” he admits. “I often had nightmares after uploading my political cartoons. I was always afraid of being arrested or attacked.”

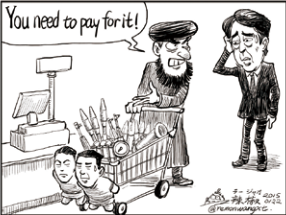

How we pay. Raising thoughts on the ISIS hostage crisis in Japan and the environmental protection of foreign leaders during APEC in China.

In Japan he has a newfound freedom. “I don't need to feel frightened here, ” he says, “even though freedom of speech in Japan is different from Western countries, which are more open. The Japanese are not as outspoken as Westerners.” He remains concerned for his safety, but doesn’t feel threatened like the cartoonists at the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo. “The Chinese government still isn’t as bad as the extremists who killed the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists. The most they did to me was shut down my sites. I’m luckier than many. I’m still alive.”

Japan now offers him a new platform for his political cartoons. “I’m hoping to create a series of political comics to help re-educate the many Chinese who have been brainwashed by the communist government, both within and outside the country,” he explains. Normally, bypassing the government censors is a major stumbling block. “Censors can eliminate Internet postings and sites by tracking certain words or names on Google and other search engines. But for cartoons, it’s not words that appear but drawings. This way they can’t catch me.”

Is he concerned about becoming a Japanese propaganda tool against his country? “I found that the extreme leftists and extreme rightists in Japan have something in common. They both hate China and the communists,” he says. “If they want to use me and my cartoons, they can. China now belongs to the communists, so if you love China, you must love the communists.”

"I had no intention of becoming an enemy of the state …. … the Chinese communist party has no sense of humor.

He’s also finding commercial success with his work after years of struggling to make ends meet. “I’ve been collaborating with the journalist Masahiko Katsuya on cartoons for his upcoming book, and also talking with other writers and several publishers about projects.”

Though he eventually wants to settle in an English-speaking country, and is now considering drawing cartoons with English translations, he’s not in any hurry. “For now, I’m happy to be in Japan,” Wang says. “I know there are plenty of cartoons I can draw about Japanese politics.”

Lucy Birmingham is a long-time, Tokyo-based journalist, scriptwriter, author and former photojournalist and president of the FCCJ.