Issue:

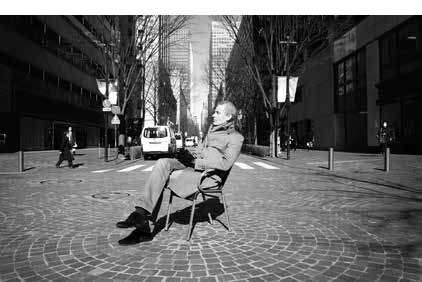

Born in 1972 in Houilles, a northwestern satellite of Paris, Philippe Mesmer grew up with a love of the sea and of ships, which led him as a young man to join his country’s navy.

He spent his days repairing aircraft, feeling all the while that something was missing. “It was so boring that I decided to leave and become a journalist,” he says. The only link between the two vocations was an inclination towards “travel and discovery.”

After taking a masters degree in journalism from Ecole Supérieure de Journalisme de Paris in 1999, he worked briefly in internet-based broadcast journalism just as the medium was getting off the ground: “It was too early, I think. The connection was still by phone and it couldn’t be viewed properly.” After another year working for a publisher in France, he found himself in Japan, due in part, he says, to a woman.

Mesmer celebrated 10 years with France’s Le Monde newspaper on Jan. 18, has worked with the news magazine L’Express for 11 years, and has written three articles in English for the Guardian. He covers Japan and the Korean peninsula as a freelancer, and says working alone suits him. “In France, for journalism, the internal politics can be very strong and very boring. Being 10,000 kilometers away from it is . . . enough.”

Although he writes about everything from business and politics to technology and sports, he prefers social issues. The ongoing story of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and the events surrounding Korea’s Sewol ferry tragedy, are particularly close to his heart.

“Both are similar in a way,” he says. “Fukushima changed Japan in 2011, and I think 2014 will be a very important year in Korea’s modern history. In both cases you have the impression that the governments are doing everything they can to forget, and the victims and their families are being misled. I like working on these stories because of their deep social implications. I don’t want these people to be forgotten.”

Mesmer is a fencer, making him an exemplar of the Japanese four-character idiom “bun-bu-ryo-do,” or the twin ways of the pen and the sword. He dabbled in Western fencing in his navy days, and began practicing kendo on his wife’s suggestion soon after arriving in Japan. He is currently ramping up efforts for a first attempt at the art’s fifth-dan examination, and says he practices less for the martial aspect and more for the physical elegance that can be achieved through years of practice.

He also has a passion for the dramatic arts. He is co-founder of the group LiberThéâtre, and has directed three plays, including Jean Anouilh’s Antigone, a work in the absurdist style that is well known in France. He enjoys the absurd because it is “just a small deviation from real-ity. It’s a useful way to slalom through life.”

“The absurd is a useful way to slalom through life”

Mesmer feels that a healthy appreciation of the absurd can help one to cope with and digest senseless tragedies such as Fukushima and the Sewol, and the often irrational human response to them. What’s more, his background in drama is occasionally useful in his journalistic work.

“It helps when you do interviews,” Mesmer says. “You can feel when someone is acting, and you’re more sensitive to gesture. Everything is dramatic play, even politics. You can see how people move and speak, how they play with anger. I remember one time I had a problem with a high-ranking official in Korea who didn’t like a story I wrote.”

He found himself summoned to the man’s office in Seoul. Having explained his position, Mesmer watched a performance unfold: “At first he was friendly, and then he became angry, because he had to. It was like a play where you know the script.”

This was during the tenure of President Lee Myung-bak, says Mesmer, when the government was pressing its members to react strongly to criticism. He waited for the drama to play out, explained that he would not change the story, and the curtains closed. “It was not a question of fact,” he adds, “it was just a question of ideas. He was only playing his role.”

Like many around the world, Mesmer was deeply affected by the murder on Jan. 7, 2015, of some of France’s best caricature satirists by two gunmen affiliated with a terrorist organization in Yemen. The incident brought issues of free speech to the fore around the world, and Mesmer wonders about the state of free speech in Japan and Korea.

In France, he says, having a point of view is perhaps the only sacred thing; everything else is open to ridicule and debate. Whereas the country’s long intellectual tradition of caricature made for genuine shock on the part of many French people at the violent reactions to the irreverent cartoons of Charlie Hebdo, he points out that there would be similar outrage in Japan, minus the violence, if the Emperor were the object of satire.

“Korea is much the same,” he says, “and there is a question in both countries regarding freedom of speech. If you read the statement issued by the Korean Presidency, and I think also by the Prime Minster’s Office in Japan, they mention terrorism and the need to cooperate etc., but not freedom of speech. That is interesting.”

As for Japan’s recently enacted state secrets law, Mesmer says he has yet to feel the chill. “I’m sure there will be a problem one day, even if it is not intentional,” he says. “Maybe a civil servant will say something to a journalist, who will repeat it without knowing that is has been classified. It could happen.

“This is 100 percent absurd, it’s like Kafka,” he laughs. When the absurdity of life begins to smack of fiction, this may be the only appropriate response.

Tyler Rothmar is a Tokyo-based writer and editor. Follow him on Twitter @TylerRothmar