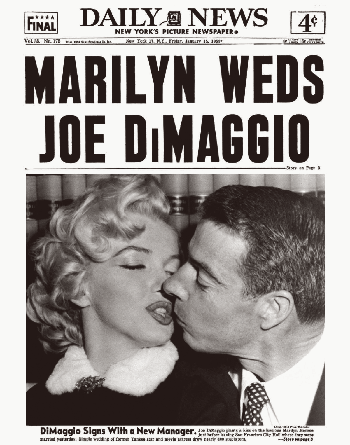

Issue:

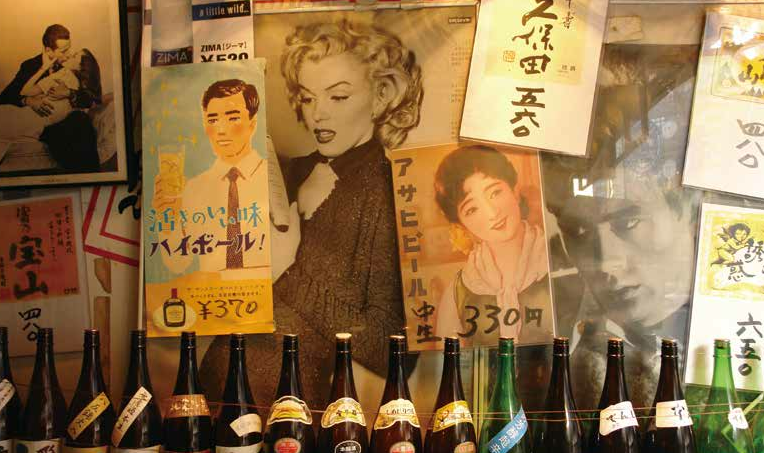

A tumultous year. Marilyn married Joe DiMaggio in January, honeymooned in Japan and split from him in October. (A bar in 21st century Japan remembers the era.)

Marilyn Monroe brought Hollywood glamor to post-war Japan, and eclipsed her famous new husband, who didn’t take it lightly.

Legendary baseball player Joe DiMaggio and his stunning new bride, actress Marilyn Monroe, landed at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport on Feb. 1, 1954, for what they were told would be a far more muted and civilized pub-lic reception than the post-wedding pandemo-nium that had stalked their every move in the U.S. That prediction, however, was off on a scale of historic proportions. At the first sight of the couple’s appearance at the door of the plane, an esti-mated 3,000 Japanese fans broke through the police security on the runway and stormed the Pan American aircraft.

Not even U.S. Air Force MP reinforcement could quell the riotous mob. Joe and Marilyn fled back inside, and finally made their exit through a rear luggage hatch into a convertible. They put the top up and promptly headed to the Imperial Hotel, skipping the planned Ginza parade route where thousands more awaited their arrival in the deep of winter.

The sight of a decoy motorcade hours later was enough to send the usually polite and orderly Japanese fans on the Ginza marching en angry masse to Hibiya, where they promptly surrounded the hotel and jammed the revolv-ing doors as they fought to enter, their overspill smashing garden ornaments and crashing through the glass walls of the lobby. The illustrious hotel which had once withstood the upheaval of the Great Kanto Earthquake was now imploding under the fury of fans scorned.

Panicking hotel management eventually persuaded a frightened Marilyn to make an appearance on the balcony. Waving to the throngs “like I was a dictator or something,” Japan’s new goddess threw them a kiss that magically lulled their earlier wrath into a purring retreat, and all soon quietly vanished back into the streets from where they came.

It was but the start of a bizarre honeymoon best remembered around the world as the first lap of the fast track to Mr. and Mrs. DiMaggio’s dramatic split less than eight months away.

Although Marilyn had already received considerable acclaim for her appearance in movies such as Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How To Marry A Millionaire, as well as her much talked-about, walk-on part in All About Eve, Marilyn’s monster roles in such successes as The Seven Year Itch and Some Like It Hot were still ahead of her. Even in America, she was not yet considered a full-fledged superstar. Yet Japan, where her every appearance provoked hysteria, proved otherwise. There was widespread debate in the Japanese media on the Marilyn phenomenon spreading uncontrollably across the country. Columnists worried that the next fashion for Japanese women would be to do away with underwear altogether, or for demure ladies in kimono to start exaggeratedly wagging their behinds. Marilyn was without question the most discussed topic in the nation’s media that year.

Joe DiMaggio, who already held a solid position in the celebrity pantheon, had good reason to think he was still the main event. Just three years earlier, he had come to Japan on a sold-out All Star tour with such players as Yogi Berra, Billy Martin, Ferris Fain, and Eddie Lopat. They had been met by thousands of devoted autograph seekers, and he remembered the adulation they had extended to him very well.

Although the honeymoon was the ostensible reason for the couple to travel together, a cursory look at Mr. and Mrs. DiMaggio’s itinerary suggests that Joe didn’t have much romancing in mind when he signed on. The tour had been arranged by Joe’s mentor from his baseball days with the San Francisco Seals, Lefty O’Doul, who was now an advisor to the Yomiuri Giants. It was, in fact, scheduled long before Marilyn had finally accepted Joe’s multiple proposals of marriage just a couple of months earlier.

The official host and sponsor of their ‘honeymoon’ was none other than the Yomiuri Giants and Yomiuri Shimbun owner Matsutaro Shoriki, who left little to chance, or heaven forbid, Marilyn’s wishes, in exploiting the windfall Hollywood spectacle. Each day was regimented around Joe’s visits to baseball camps, coaching and interviews, with a few days thrown in at a luxury resort for golf, another activity that left Marilyn out. Their visits to Osaka, Fukuoka and Hiroshima were all about baseball. Everything was meticulously orchestrated to give the still struggling Giants and Japanese professional baseball a boost in postwar Japan.

Marilyn’s usefulness was bountifully evident early on, and Shoriki was delighted. Trouble was, the cameras and the fans loved her just a little too much for Joe’s very small comfort zone. Each time Marilyn appeared in the stands to support her husband’s high-profile coaching sessions, all thought of baseball quickly left the spectators’ minds . . . and too often the players’ as well.

Reports of loud arguments in their suite and camouflaged bruises started to circulate almost immediately. Marilyn’s bandaged arm in a splint only fuelled the rumors of a meltdown. Joe sulked publicly, while Marilyn exuded her trademark transcendental sweetness, betraying only the rarest glimpses of boredom as she dutifully accompanied her husband to endless baseball photo ops and receptions.

No wonder then, that Marilyn lunged at the chance to take time out from her honeymoon to entertain the troops in Korea. The idea was first planted before Marilyn had even touched down in Tokyo, and was formalized soon after with the arrival of an official invitation from General John E. Hull, commander of U.S. forces in the Far East. The dates coincided with yet another Central League training camp appearance for Joe. How perfect.

Marilyn did make some effort to engage her husband’s support in the new patriotic endeavor, but was rebuffed.

“Go if you want to,” DiMaggio famously suggested. “It’s your honeymoon.”

The Marilyn who the Japanese remember from 1954 bore little resemblance to the troubled actress known for chronic tardiness on shoots and her increasingly debilitating fear of standing before the camera, exacerbated by a pill-induced pattern of destructive behavior. Accounts from Japan and Korea marveled at her professionalism and thoughtfulness.

Travelling from camp to camp in Korea, she never asked for special dressing rooms, often changing at the last minute behind the curtains from flight jacket and boots to show-stopping attire. Hotel staff reported their astonishment that Hollywood’s most beautiful star would wash her own lingerie. One Japanese bellboy recounted in an interview that Marilyn was not like the usual foreign visitor at his hotel who leaves a mess. “She is meticulously tidy,” he gushed, “perhaps the tidiest foreign guest we’ve ever had.”

Her conquest of the U.S. troops in Korea on the whirlwind tour of the frozen fronts created nonstop bedlam and marked, perhaps, the happiest moments of her career. Performing live concerts, particularly in front of such large, wild audiences, was unfamiliar terrain, but the moment she stepped out for her first song of the tour at a remote mountain tent camp, she was truly in her element.

Cameras on movie sets could trigger hives of anxiety, but Marilyn’s legendary hold on men in face-to-face encounters empowered her. The hardy Marines braved the freezing temperatures in hooded parkas and boots to see the woman of their dreams appear before them in a revealing, wisp of a dress with thin spaghetti straps. The boys went wild. Snow was falling on her bare arms, but in facing the 17,000 yelling soldiers, she was to recall years later, for the first time in her life, “I felt . . . no fear of anything. I felt only happy . . . I felt at home.”

To be fair to DiMaggio, not many husbands would have been happy to witness such worshipful fixation bestowed on their wife . . . and he had good reason to believe she reached out for it. To make matters irreversibly worse, the world was not that interested in what Joe was doing for Yomiuri. So it must have been more than a little painful to have your wife then gush upon her return to Tokyo, “It was so wonderful, Joe. You’ve never heard such cheering.” To which Mr. American Icon could only reply, “Oh yes I have.”

Ultimately, not a whole lot is known of the impressions she actually took home from Japan, but there are mountains of anecdotes in which Marilyn made indelible impressions with small acts of kindness and genuine delight in the encounters with the Japanese people on tour. It was, however, quite the opposite from what witnesses described as the routinely surly behavior of the groom who obviously felt eclipsed on a trip that was to have showcased his charisma and impressed upon his bride the scope of his international stature.

In reality, Joe and Marilyn’s marriage never seems to have enjoyed a good stretch, and the disastrous Tokyo honeymoon was but a start to an intense and mercifully short chapter of her life. It’s well known that DiMaggio was to carry a torch for Marilyn right until her untimely death . . . and beyond.

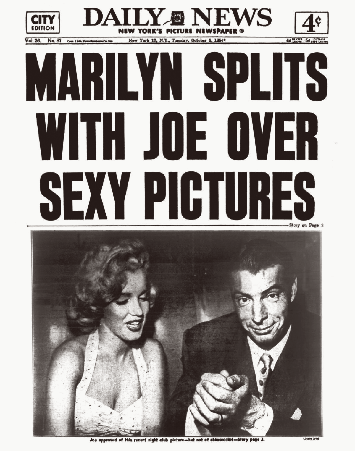

What was called a “nine month misunderstanding” reached its cataclysmic finale shortly after their return from Tokyo, when Marilyn’s infamous white skirt billowed high above her head during the filming of The Seven Year Itch. The incident, unfolding as it did in front of thousands of New Yorkers eager to catch a glimpse of Marilyn, raised Joe’s obsessively jealous behavior to new heights and the ensuing violence appeared to have accelerated the inevitable breakup.

Weeks later, Marilyn sued for divorce on grounds of mental cruelty. It was an ending all but impossible to imagine a few months earlier, when their ecstatic smiles at the start of their Tokyo honeymoon touched off the most frenzied mob adulation Haneda had ever witnessed.

Mary Corbett is a writer and documentary producer based in Tokyo.