Issue:

November | Ripping Yarns (Part 1)

Meeting Norodom Sihanouk in Pyongyang was just a prologue to my North Korean adventure

North Korea began to open its doors a little in the 1980s as it became increasingly clear that Kim Il Sung’s policy of Juche self-reliance and isolation was leaving it far behind.

Across the Yalu River, the Chinese dragon was stirring after decades of Maoist madness. Kim Il Sung’s other patron, the Soviet Union, was manifestly failing to narrow an ever-widening gap with the capitalist West. South of the Demilitarized Zone, the looming Olympic Games in 1988 was shining an unwelcome torch on Seoul’s prosperity and self-confidence.

In late 1984, an American journalist from Cox News Service was invited to North Korea, and his conscientious, if rather dull, reporting from one of the most closed countries on earth whetted the appetite of foreign editors. In Tokyo, the only visible route for Western journalists to gain entry to North Korea was cajoling Chongryon, the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, which in the absence of diplomatic relations functioned as a de facto embassy. Its man charged with handling the foreign press, Choe Kwan Ik, was often to be seen in the FCCJ being plied with drink and victuals, at the end of which he would invariably conclude that a visit would be “very difficult, if not impossible”.

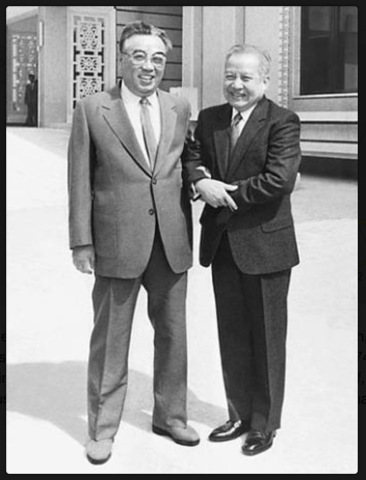

Ed Reingold, the trumpet-playing Tokyo correspondent of Time and a former FCCJ president, asked me one day in the Club how I was doing, and I told him of my frustration in dealing with Mr. Choe. “Sihanouk is staying in Pyongyang. Kim Il Sung built him a palace there. Why not ask him for an interview?” Reingold suggested.

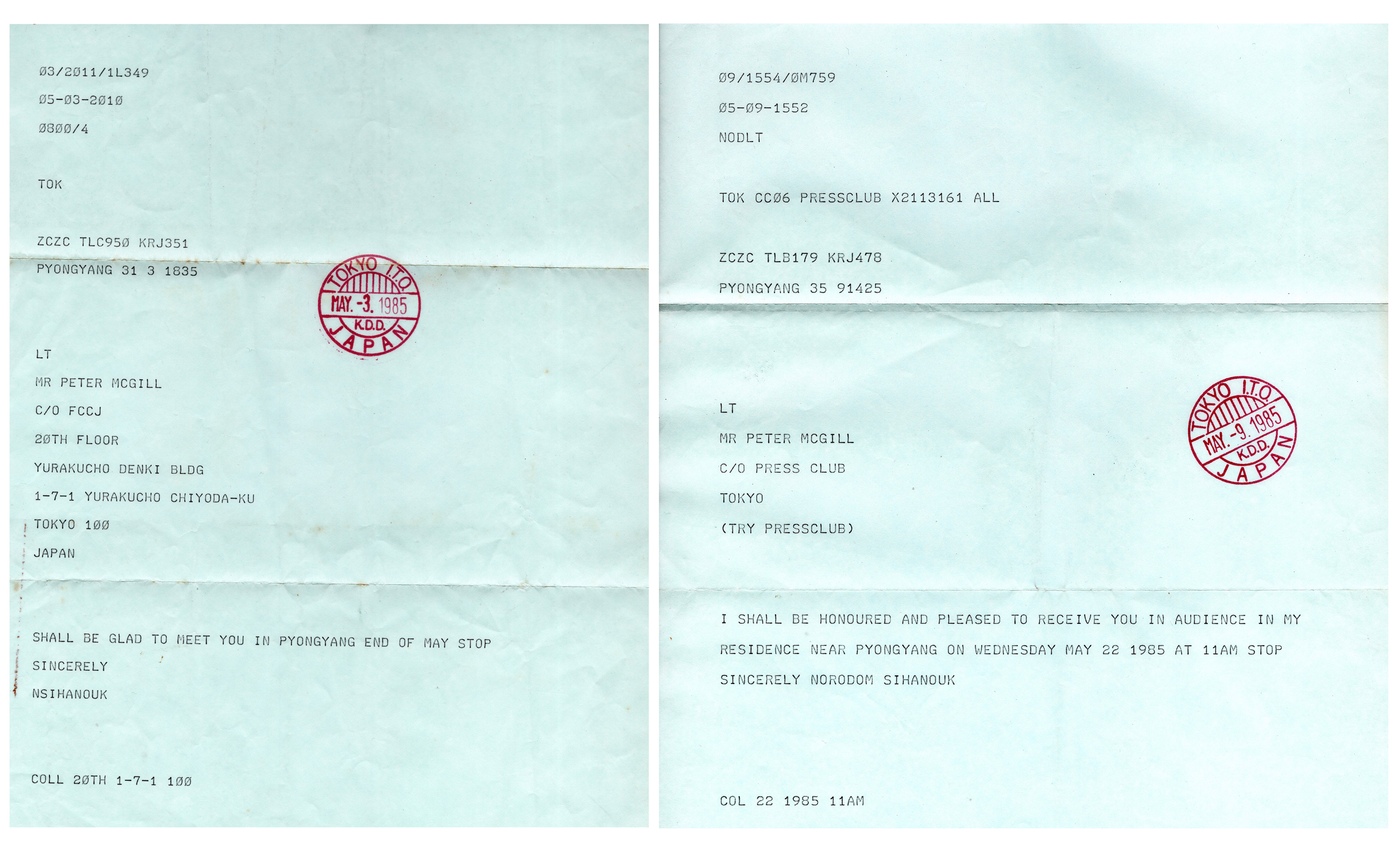

I was 27 and full of adventure and ambition. The idea seemed wildly unlikely but worth a go. I composed a request for an interview in Pyongyang regarding “developments in Cambodia” and sent a telegram from the nearest KDD office, addressed to His Royal Highness, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, Pyongyang. To my gleeful amazement, a reply came on May 3: SHALL BE GLAD TO MEET YOU IN PYONGYANG END OF MAY STOP SINCERELY NSIHANOUK

I immediately informed my two paymasters – The Observer of London and Maclean’s magazine in Toronto – as well as my nemesis, Mr. Choe.

“Is this an invitation?” Choe scoffed when I showed him the telegram in the FCCJ. I replied that Cambodia’s exiled monarch was a friend of Kim Il Sung, “your Great Leader,” and that his words should be taken seriously, but Choe demanded more substance. I duly contacted Sihanouk, and on May 9 he wired back: I SHALL BE HONOURED AND PLEASED TO RECEIVE YOU IN AUDIENCE IN MY RESIDENCE NEAR PYONGYANG ON WEDNESDAY MAY 22 1985 AT 11AM STOP SINCERELY NORODOM SIHANOUK.

Choe reluctantly grunted acknowledgment when shown the second telegram. A few days later, I was told to collect a visa at the North Korean embassy in Beijing. After explaining the purpose of my trip, I was granted a double-entry visa by China.

This flurry of favours went to my head, and I was half-expecting to be greeted by some flunkey at Beijing’s Nanyuan Airport. No one was waiting. This was a foretaste of my disappointment at the gargantuan Beijing Hotel overlooking Tiananmen Square that was fully booked. Waving light-blue telegrams from Prince Sihanouk at the stony face of the reception manager had no magical effect. Bored diplomats from developing countries, sprawled across upholstered chairs in the vast entrance lobby, observed my walk of shame back to the taxi stand. It was to be the same story everywhere I tried that night, in person or by phone. Dishevelled and exhausted, I ended up sleeping on a bench in the corridor of a hotel basement. I was awakened by kitchen staff preparing breakfast. It was only by calling Tokyo and pulling some strings that I was able to spend the next night on a bunk bed in a Chinese boarding school.

Next, the embassy of North Korea had received no word from Pyongyang and told me to come back the next day. When authorization eventually came through it was for a stay of 48 hours in Pyongyang.

On the tarmac our Air Koryo jet was kept on hold pending the arrival of someone very important. My fellow passengers at the rear of the small Soviet jet included the national football team of Singapore, a representative of the World Food Programme, and an unassuming fellow Brit with a beard. The dignitary turned out to be Makoto Tanabe, the secretary-general of the Japan Socialist Party (Nihon Shakai-to). Japan’s main opposition party was trying to distance itself from its Marxist-Leninist roots and had recently gone so far as to accept the existence of the Self-Defence Forces, but still clung to fraternal ties with the Korean Workers’ Party.

As we flew over the Changbai (Paektu) Mountains, an Air Koryo stewardess dispensed bottles of Pyongyang Beer and chewy strips of dried squid. I steeled myself for what promised to be a difficult discussion with whomever had been chosen to be my minder.

The terminal building of Pyongyang’s Sunan Airport was bedecked with streamers welcoming Tanabe, and a brass band was playing in his honour. After what seemed an eternity, the rest of us were allowed to disembark and hustled through a side entrance.

As soon as I was through passport control and customs, a beaming Korean man approached. Dressed in tweed jacket with the obligatory lapel badge of the Great Leader, my minder introduced himself, in fluent English, as “a teacher”.

We sat down for a talk. I protested, in the politest of terms, at being given just 48 hours to stay in North Korea. “But Mr. McGill, you only need 48 hours for the interview with Prince Sihanouk!” “Ah yes, but you must understand that is also a great honour and privilege to be allowed to visit your country, and of course my publications are expecting me to write about that as well. If I am to be granted only 48 hours, it may not leave me with a favourable impression of the People’s Paradise.” He stared at me intently and gave a faint smile. “Please wait while I consult the foreign ministry.” He adjourned to a telephone booth, returning after 10 minutes. “You have been given five days.”

After checking in at the Pothonggang Hotel, I met a talkative Swedish man in the lobby, who said he was a consultant to the North Korean government on international maritime law. I asked why he wanted the position. “I charge US$400 a day plus expenses” came the snappy reply (US$400 then being a tidy per diem). He advised me that my room would almost certainly be bugged and searched every day by the chambermaid. To butter up the authorities, he pretended to be reading the Selected Works of Kim Il Sung, a copy of which, like the Gideons Bible, was to be found on every bedside table. “I turn over a few pages in the morning and leave a new marker,” he explained.

Famished, I headed to the dining room where I found myself the only customer. I ordered a grilled half chicken and contemplated a giant mural of a cornucopia. Joyous Korean farmers, their arms bulging with muscles, were driving tractors, and their ruddy-cheeked wives were harvesting the bounty of the land. Besides bushels of wheat were baskets overflowing with vegetables and shiny fruit. I looked forward with ever greater relish to the chicken. It came at last, a half-starved skeleton with little even to pick at.

Back in my room, I decided to place a call to the Observer foreign desk in London. Unlike James Bond, I did not bother unscrewing the mouthpiece to check for listening devices. It must have been a landline via Moscow, and we shouted to be heard above the crackle.

After a much-needed hot bath, I pondered what I would ask the exiled monarch of Cambodia in the morning. I was too young to have been part of the “Vietnam War Generation” and the prospect filled me with not a little trepidation.

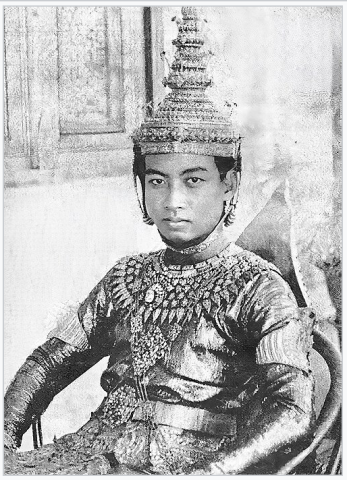

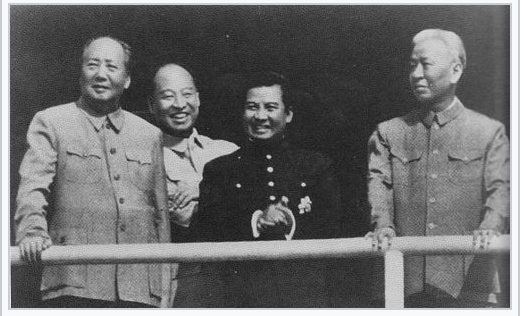

Sihanouk had been a central figure in the great backwash from decolonisation in Southeast Asia, wresting Cambodian independence from the French in 1953 when they were mired in a war against the Vietnamese. Sihanouk’s Cold War embrace of neutrality was interpreted by the Americans, Thais and South Vietnamese as appeasement of communism, and a failed coup d’état in 1959, coordinated by the CIA’s ethnic Japanese station chief in Bangkok, Victor Matsui, deepened Sihanouk’s distrust of the United States.

The “Ho Chi Minh Trail” North Vietnam used to supply its forces in South Vietnam cut across eastern Cambodia with Sihanouk’s tacit blessing. In 1969, Richard Nixon approved Henry Kissinger’s plan to disrupt the supply line through a four-year-long secret campaign of carpet bombing that by some reckonings killed hundreds of thousands of Cambodians. Sihanouk was on holiday in France in 1970 when he was ousted from power in a coup led by Lon Nol, a pro-American general. China offered sanctuary and encouraged Sihanouk to join forces with the Cambodian communist movement he had labelled the “Khmer Rouge” and which was cooperating with the North Vietnamese against the Lon Nol regime. The degree of American support for Lon Nol’s coup is still debated, but Sihanouk had little doubt, entitling his 1973 memoir My War With the CIA: Cambodia’s Fight for Survival.

After the Khmer Rouge took power in 1975, they discarded their united front with the North Vietnamese, and the former playboy was held for three years as a prisoner in the royal palace in Phnom Penh. Sihanouk had no way of foreseeing the hideous Khmer Rouge genocide that killed between two and three million people in a nation of only seven million. Five of his children and 14 of his grandchildren were murdered during this period.

When invading Vietnamese forces overthrew Pol Pot in 1979 and installed the puppet regime of Heng Samrin, Sihanouk was released. Reckoning the Vietnamese to be an even worse enemy, in 1982 he joined an uneasy coalition of the Khmer Rouge and non-communist forces that battled Vietnamese troops. Supporters of Sihanouk in the West found this hard to accept, as the Vietnamese occupiers had at least stopped The Killing Fields, the title of a moving 1984 biographical film. The realpolitik of Western and Chinese governments prioritised curtailing the expansion of Vietnam, which was backed by the Soviet Union, even if that meant turning a blind eye to Khmer Rouge atrocities.

Chandeliers and caviar

On the anointed morning, a chauffeur-driven Mercedes took me to a wooded hillside overlooking a lake, where Kim Il Sung had ordered the Korean People’s Army to construct a 40-room mansion fit for an exiled king. In the wood-panelled interior of what Sihanouk jokingly called “my palace”, there was a chandelier-lit dining room and a ballroom for dances, ornate guest rooms, a courtyard and executive offices, plus 100 Korean staff at his beck and call. In the gymnasium by the lake Sihanouk enjoyed played badminton with the Pyongyang-based diplomats, and would often take his Maltese poodle, Miki, for pleasant walks along the winding paths through the woodland, where one often heard the calls of pheasants. The Great Leader had even provided a Buddhist temple, and of course, footed the bill for Sihanouk’s frequent travelling and expensive tastes in tailoring, champagne and caviar.

When I had stopped gawking and banished recent painful memories of basement benches and dormitory bunks, I asked Sihanouk a series of questions about the war then being waged and the future of Cambodia during a two-hour interview, on which I based articles for the Observer and Maclean’s. Staff at the Pothonggang Hotel spent hours telexing the copy. After a blizzard of telexed typos had been corrected there was no time to ponder the significance of having just met one of the most remarkable political figures of the 20th century. North Korea, the real reason for my trip, beckoned (to be concluded).

Peter McGill is a former president of the FCCJ.