Issue:

November 2025

Fear of Russian espionage gripped Japan decades before Richard Sorge did Moscow’s bidding

On February 24, 2022, the same day that Russia launched its “special military operation” against Ukraine, mystery author Stan Guy had invited me to accompany him on his monthly visit to his late wife's grave in Tama Cemetery. Having extra time, we stopped off to visit the graves of several famous historical figures interred there.

One such individual was Soviet master spy Richard Sorge (pronounced ZOR-gay). We found Sorge's grave festooned with fresh red flowers and a wreath. By happenstance, it seems the previous day, February 23, had been a Russian national holiday originally commemorating the founding of the Red Army, but since 2002 the holiday had been renamed Defender of the Fatherland Day.

Sorge, a journalist accredited to the Frankfurter Zeitung and a card-carrying member of the Nazi Party, gained the confidence of Eugen Ott, the German military attaché in Japan and later ambassador. The intelligence he obtained on German and Japanese military plans was transmitted by code to Moscow.

Sorge's dispatches indicating that Japan would refrain from attacking the Soviet Far East are believed to have influenced Stalin's decision to transfer Red Army troops from Siberia to the defense of Moscow, thwarting Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union that began in June 1941.

Sorge, a heavy drinker who was rather sloppy in his efforts to conceal his activities, was arrested on October 18, 1941, along with other members of his ring. He was found guilty of espionage and hanged at Sugamo prison on 7 November, 1944. His Japanese confederate, the Asahi Shimbun journalist Hotsumi Ozaki, was executed the same day.

Decades earlier, incidents involving Russian spies in Japan were already making headlines.

Japan emerged victorious from a bloody war against imperial Russia in 1904-1905. After a month of negotiations held in the U.S. city of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the hostilities were concluded on September 5, 1905, with the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth. The treaty was signed on 5 September and ratified by the Privy Council of Japan on 10 October, and in Russia on October 14, 1905. For his role in mediating the negotiations, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt became the first American to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

Among the victor's spoils, the treaty recognized Japan's hegemony in Korea (which soon afterwards became a protectorate, followed by its full annexation into the Japanese empire in August 1910); awarded it Russia's lease on the Liaodong Peninsula (which became known as the Kwantung Leased Territory); granted Japan the Russian-built South Manchuria Railway; and ceded to Japan half of the island of Sakhalin (referred to by Japanese as Karafuto) south of the 50th parallel.

Many Japanese were nonetheless infuriated by what they saw as the “humiliating” terms of the treaty. Converging on Tokyo's Hibiya Park from September 5, their riots resulted in the collapse of the government headed by Taro Katsura and a declaration of martial law. By the time order was restored two days later, mobs had destroyed or damaged more than 350 buildings, including 70% of the koban police boxes in the capital. Casualties included 17 deaths, with over 450 policemen and 48 firemen injured. Police made over 2,000 arrests, of whom 87 were eventually tried and found guilty. Riots also broke out in Kobe and Yokohama. Martial law continued until November 29.

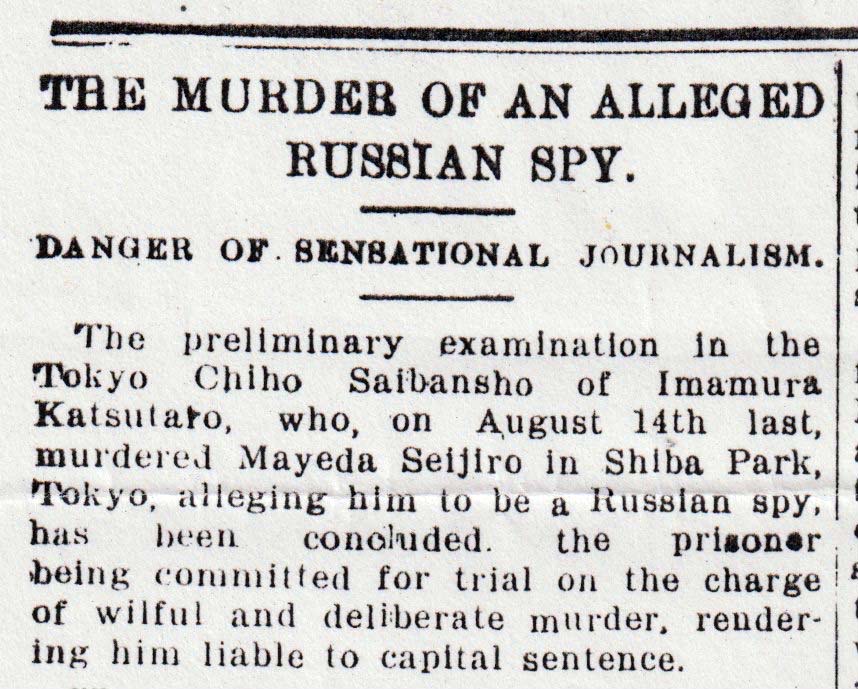

Nationalists' anger continued to fester, regularly stirred by the media. In August 1907, Seijiro Maeda, a Japanese-language instructor at a language school in Vladivostok, was stabbed to death on the street in Tokyo's Shiba district by 30-year-old Aomori native Katsutaro Imamura.

After reading news reports about Maeda in the newspapers, Imamura became convinced Maeda was a traitor and likely sent by Russia to spy on Japan.

Originally from Mie Prefecture, the 29-year-old Maeda had learned Russian from linguist Shimei Futabatei, after which he moved to Siberia and taught Japanese to Russians in Russia, eventually becoming a naturalized Russian citizen. The actions of such an “international person” were not understood by the general public, and when the media learned that Maeda had returned to Japan on a visit, newspaper articles began appearing that described him as a suspicious person.

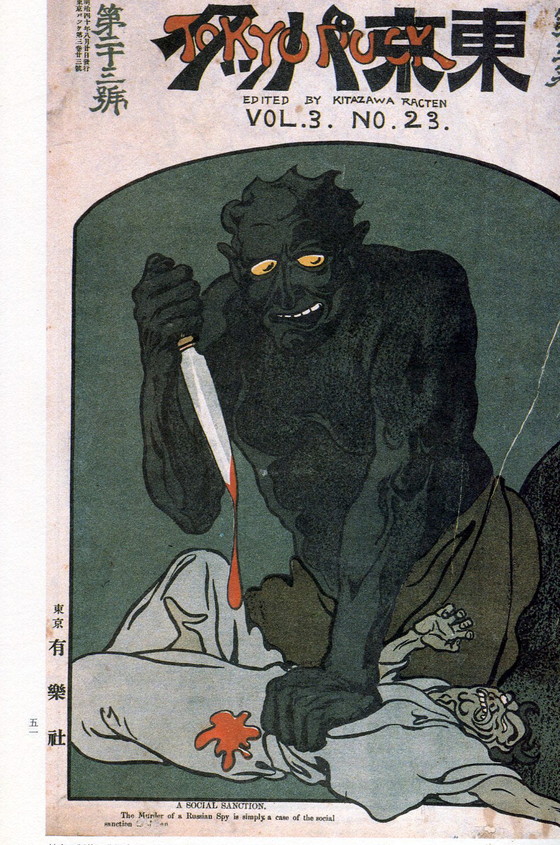

Shortly before he was murdered, Maeda told Futabatei of his innocence and complained over his treatment by the newspapers. Subsequent to the murder, newspaper articles appeared with headlines like “Spy punished,” which reported that Maeda was not only a spy, but also a morally corrupt person who deserved to be killed.

The Japan Weekly Chronicle of November 14, 1907, provided this account: “The prisoner, according to his own statement, read ... in the Hochi Shimbun of August 3rd last to the effect that Maeda had joined the Russian army during the war and shamelessly returned to this country ... staying at the Chuo Hotel at Gorobeicho, Kyobashi-ku, Tokyo. Thereupon, the prisoner decided to find out for himself whether Maeda was really "a seller [i.e., traitor] of his country” ... as alleged by the paper, and visited the hotel several times to see him.

“On the 4th of August, he succeeded in obtaining an interview. He then introduced Chiyotaro Maruo to him, and these two men took it upon themselves to watch the movements of Maeda. While they were so engaged, the prisoner made the acquaintance of Takasuka Junpei, a member of the editorial staff of the Asahi Shimbun, who frequented the hotel with the same object as that of the prisoner. After this the two men worked together; sometimes under the direction of Takasuka or at his own accord, the prisoner would visit the hotel and at last he became very familiar with Maeda, occasionally going to entertainments with him.

“In this way, the prisoner managed to discover the personal affairs of Maeda and, finding that he had lived for a long time in Vladivostok as an Instructor in the Russian Oriental Language School there ... drew the conclusion that he was exercising a censorship over Japanese newspapers. The prisoner discovered that upon the outbreak of hostilities with Russia, Maeda was quite indifferent and remained in Vladivostok, despite the fact that all other Japanese left there. In addition to this he applied for permission to be naturalized as a Russian subject, and adopted the Christian faith, strenuously endeavoring by all these means to court the favor of the Russians. After the restoration of peace, he continued to work for the ... School as before, and subsequently became naturalized as a Russian …

“Accused 'found Maeda's action and words suspicious in every respect,' but still failed to secure evidence to prove...that Maeda was acting as a spy...when he learned that Maeda was preparing to leave Tokyo.

“He picked up some ashes from a fire-box in an adjoining room, and concealed the dust in the sleeve of his kimono, his purpose being to use the ashes for temporarily blinding his victim. He then made his way into the kitchen and there unsheathed a small sword, which he carried concealed on his body. Wrapping the sword in a handkerchief, he returned to the room where Maeda was waiting and stabbed him. Maeda ran out of the house, and the prisoner followed after him, until the unfortunate Maeda came in front of the Teikoku Gunjin Koyenkai [a soldiers' welfare organization], where he sank to the road. Imamura again stabbed his victim, this last thrust of the sword proving fatal.

“There are many mysteries surrounding this case, and it seems that there was also a relationship with the military police and newspaper reporters behind it. In any case, many people thought Maeda was suspicious, and the moment he was thought to be suspicious, he was literally in danger.

As stated the Court found that the action of the prisoner rendered him liable to capital punishment as provided by Article 292 of the Criminal Code, and remitted him for public trial.”

On December 28, 1908, the Tokyo District Court found Imamura guilty of homicide and sentenced him to 12 years in prison. The prosecutor had demanded the death penalty, but in the eyes of the judges Imamura's "patriotic" motives justified a more lenient ruling.

Things Russian would remain suspect in Japan for many years to come. Long before the Sorge spy ring began its activities in Tokyo, the Japan Weekly Chronicle of April 26, 1923, reported: "Spy-mania works curiously at times. A Russian priest, Mr. Serisheff, was given permission to visit the schools of Japan to obtain first-hand information on the education system. He chose to make the journey on foot and soon found that he was being tracked from village to village by the police. He has been recounting in an Osaka publication how he made the best of a bad job, treating his spies as comrades and making good use of them to ensure that he should get the best possible accommodation at the lowest possible price. Osaka Socialists have a story of one of their number who frequently visits Kyoto. He always informs the police of his intention to go there, and they promptly send an escort, who obligingly pays the Socialist's fares."

At least some efforts were made to curb the hysteria. The Hiroshima Prefectural Police issued a notice concerning incidents of people being instigated by newspapers and other media, such as insulting the Russian Orthodox Church and assaulting believers, and a measure was put in place to crack down on such unscrupulous people from the perspective of religious freedom. Seiichi Higaki, who worked at a police station during the Russo-Japanese War, recalled that he received many reports of “be careful, it might be spies”, but that "it was staggering how many of the ordinary people who were so sensitive about it thought it was nonsense".

Nonetheless a fair number of "ordinary people in the three houses around the corner" were caught up in the spy fever.

The authorities made some attempts to provide guidance, but these "ordinary people" were getting carried away, and behind that frenzy were the newspapers that were fueling the crisis.

The expression “ordinary people in the three houses on either side of the street” was extracted from the famous opening of Soseki Natsume's 1906 novel, Kusamakura (The Three-Cornered World). From its English title it can be said that an artist is a person who lives in the triangle that remains after the angle which we may call common sense has been removed from this four-cornered world.

Soseki had written: “The one who created the human world is neither a god nor a demon. It is the ordinary people who flicker around the three houses on either side of the street. Even if the human world created by ordinary people is difficult to live in, there is no country to move to. If there were such a place, we would just go to a country of inhuman people. A country of inhuman people is even more difficult to live in than the human ”

A resident of Tokyo since 1966, Mark Schreiber has authored two nonfiction works about historic crimes in Japan.