Issue:

November 2025

Japanese criticism of Israel has risen in recent month, but Sanae Takaichi’s arrival could change that

Since Hamas’s October 7, 2023, attack on Israel, Japanese media outlets have published more about Israel than in any other timespan in recent memory.

With a fragile ceasefire in place as of writing, the past two years of media coverage, diplomatic statements, and recent changes in Japanese politics point to a general continuity in Israeli-Japanese relations, but also the growing impact of negative public sentiment about Israel in Japan.

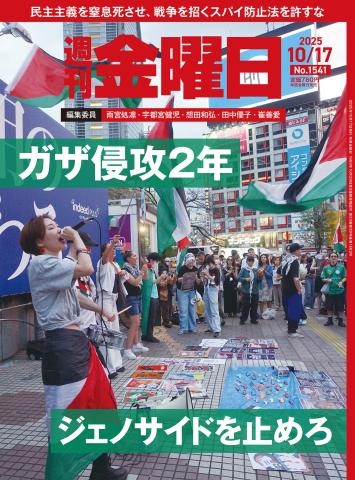

The sheer scale of the humanitarian crisis in Gaza has led to widespread coverage in the Japanese press, as well as the publication of books and opinion pieces lambasting Israel’s government and military. And increasingly, local Japanese politics has seen the condemnation of Israel and calls to protect civilians and human rights in Gaza. Already in 2024, a fracas broke out over the decision not to invite Israel to Nagasaki’s ceremony marking the 79th anniversary of the atomic bombing, while 28 of Japan’s 47 prefectural assemblies passed resolutions calling for a ceasefire and the protection of human rights in Gaza.

In February this year, the then prime minister, Ishiba Shigeru, pledged Japan would accept and provide medical treatment to Palestinians in Gaza who were not receiving adequate medical care (with the first two patients confirmed by the then foreign minister, Takeshi Iwaya, in March). On October 9, Ishiba’s chief cabinet secretary, Yoshimasa Hayashi, pledged Japan’s support for reconstruction in the Gaza Strip. Like Kishida before him, Ishiba’s administration tried to balance humanitarian interests with proclamations acknowledging Israel’s “right to defend itself and its people in accordance with international law” – thereby aligning itself with other G7 nations.

However, as in some other G7 nations, the growing domestic outcry against Israel in the form of weekly protests in Japan’s metropolitan areas appears to be percolating into national politics. In September, the then prime minister, Shigeru Ishiba delivered powerful words at the United Nations’ General Assembly.

“I feel strongly indignant by the statements made by senior Israeli government officials that appear to categorically reject the very notion of Palestinian state-building,” he said.

“We must never overlook the unimaginable hardships the people of Gaza are facing. Japan has consistently supported the lives and dignity of the people of Gaza through humanitarian assistance, including the medical treatment of the wounded in Japan. We will continue to make every possible effort.

Last year, Japan’s House of Representatives passed a resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza. The proliferation of media stories about Israel over the past two years appears to be shifting in tandem with both public and private Japanese opinion toward Israel.

However, in a 2004 research article Raquel Shaoul explained that Japan’s risk-averse Middle East diplomacy had long prioritized access to oil. Concurringly, Evangeline Cheng recently observed in The Diplomat that the Japan-led Conference on Cooperation among East Asian Countries for Palestinian Development exemplifies the (continuing) Japanese approach to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: “cautious, development-oriented, and rooted in quiet multilateralism”. And, despite calls to action in Japan to help alleviate suffering in Gaza, Professors Kikkawa and Shiraishi of Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University ended a recent article on the prospects of Japanese support for refugees by saying, “In light of Japan’s history and public opinion, its humanitarian aid policy is unlikely to suddenly change to accept many refugees.”

So, what can a swell of media coverage about Gaza, Israel, and Palestine tell us about whether there is actually a link between shifting public opinion and policy in Japan?

To begin, articles by Japanese voices spanning academia, cultural criticism, politics, and the news media have frequently moved beyond just criticizing Israel’s campaigns in Gaza, and often indicted Israeli society at large.

One example of this foundational Japanese criticism of Israel is captured in the recently published book by veteran Mainichi Shimbun reporter Tomoko Ohji, The Worldview of Israelis. This book’s release was accompanied by coverage in outlets such as Yahoo News and the Nikkei. And notably, an article entitled “The people who experienced the Holocaust, why…?” introducing some of the book’s main points, appeared in the July/August issue of Gaikō (Diplomacy), a magazine published by Japan’s foreign ministry.

But Ohji is hardly alone.

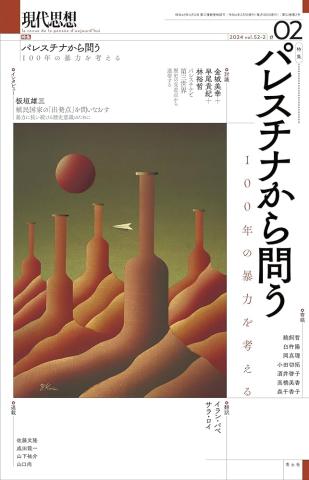

Myriad contributors to Gendai Shisho’s special issue on Palestine released last February condemned the October 7 attack on Israel and Hamas’s governance of the Gaza Strip, but also caustically reproved Israel’s “overwhelming violence” (Yoshiko Kurita). In the same issue, Kyodo News’s Jerusalem Bureau Chief, Yūgo Hirano chronicled his visit to northern Gaza on December 8, 2023, along with other reporters. Hirano devoted more than a fifth of his article to outlining the specifics and devastation of the October 7 attacks, with the remainder decrying Israel’s campaign.

Special issues such as Gendai Shisho’s, as well as books emblazoned with “emergency publication” (kinkyū shuppan), editorials, essays, and opinion-pieces have presented Israel’s response to October 7 as disproportionate, adding to its alienation on the world stage.

Leading Japanese publications have directly compared Israel’s post-October 7 actions to the Holocaust. For example, the Asahi Shimbun published a front-page editorial to coincide with the 85th anniversary of Kristallnacht (the "night of broken glass" pogrom that took place on 9-10 November, 1938), which reads: “The history of the Jewish people is marked by unspeakable discrimination and hardship, none of which humanity should ever forget.

“But now, it is none other than the Jewish people themselves who are raining bombs of retaliation on Palestinians, whom they have kept in what is basically an “open-air prison.”

Even right-leaning publications have started criticizing not just Israel’s military campaign, but Israeli society as a whole. Last week, in the pages of the conservative Sankei Shimbun, their Middle East Bureau chief, Takao Sato, described Israelis as largely “indifferent” to Palestinians’ suffering and Israel’s increasing international isolation.

But while such representations of Israel are now commonplace in Japan’s media, before October 7, Israeli-Japanese diplomatic, economic, and security relations were at a high point.

Following a rapprochement of Israeli-Japanese bilateral ties by the second administration of late former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo (December 2012 until September 2020), Japanese investment in Israel reached a record $3.5 billion in 2018 after a Japanese-Israeli investment agreement was signed the previous year. Israel became Japan’s first industrial research and development agreement partner in 2014, a joint cyber-defense agreement was signed in 2017, and Israel’s flagship carrier, El-Al, began direct flights to Narita Airport in 2023, its services having previously been limited to Kansai International Airport.

Over the past two years, the Fumio Kishida and Ishiba administrations have walked a fine line between advocacy for a two-state solution and echoing other G7 countries’ support for what former Kishida’s foreign minister, Yoko Kamikawa, noted as Israel’s right to self-defense under international law.

Critical voices have emerged even within Japan’s long-dominant Liberal Democratic Party. Taro Kono, who previously served under the Abe as chairman of the National Public Safety Commission, foreign minister and defense minister, posted on X on July 26: “Japan should have recognized the state of Palestine earlier. 146 Members of the both Houses of the Parliament of Japan had requested the Government to recognize the Palestine state in the Parliamentary session.”

At an August 6 press conference at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan, Kono said, “We should have been the first government to recognize the State of Palestine, but now we are missing the bus, and I really regret it.”

But while some politicians have argued for a more explicitly pro-Palestinian policy, leading up to the September 22 UN High-level Conference on the Two-State Solution, Chief Cabinet Secretary Hayashi Yoshimasa had not closed the door on Japan recognizing Palestinian statehood, saying: “As Japan supports a two-state solution, it is a matter of when, not whether, to recognize [Palestinian statehood] … We will comprehensively examine the matter, while closely monitoring changes in the situation.”

At the UN conference, Iwaya explained that “For my country, the issue of recognizing a Palestinian state is not a matter of ‘if’, but of ‘when.’” At an October 7 news conference, Iwaya said that if the two-state solution was “completely undermined”, Japan would consider “all options, including sanctions [on Israel] and recognition of a Palestinian state”.

The Pew Research Center released the results of a survey conducted this year across 24 countries about attitudes towards Israel. The 79% of Japanese respondents who had a negative opinion of Israel was exceeded by people in only two other countries (Indonesia and Turkey, at 80% and 93%, respectively).

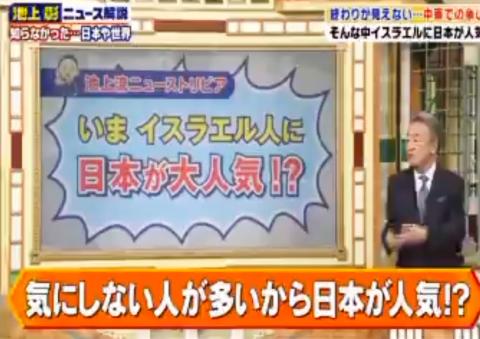

In August last year, the popular commentator Akira Ikegami said in a TV broadcast that if an Israeli citizen came to Japan on an Israeli passport, nobody reacts. "I don’t know whether this is something to celebrate or not,” he said.

But Ikegami’s sweeping assertion was somewhat dubious. The cancellation of an Israeli traveler’s hotel reservation in Kyoto in 2024, and a separate Kyoto-based lodging’s request this year that an Israeli guest sign a pledge that they had not committed war crimes, received coverage in the domestic and international media. Both incidents triggered interventions from the Israeli ambassador to Japan, while the Los Angeles-based Simon Wiesenthal Center denounced the 2024 incident as part of a rising tide of post-October 7 antisemitism in Japan.

Politically, Iwaya’s statement that Japan will recognize a Palestinian state is not the only concrete shift. Against voices in the U.S. and Israeli governments, Japan resumed funding for the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) in April 2024 after initially suspending funding in January 2024, following allegations that UNRWA staffers had participated in the October 7 attacks.

Additionally, the Japanese government sanctioned Israeli settlers in the West Bank for the first time, with the then chief cabinet secretary, Hayashi Yoshimasa saying on July 23, 2024, “Such acts as violence, threats, and destruction of property by some extremists against Palestinian communities and others have become a serious problem, as they frequently kill or injure Palestinian residents or force them to leave their homes.”

Kamikawa had earlier presaged such a move, telling reporters at an April 2, 2024, press conference: “Japan’s position is that Israeli settlement activities are in violation of international law and undermine the viability of a two-state solution … In addition, violence by extremist Israeli settlers is never acceptable, we will continue to consider what kind of measures we can take to clearly express such positions of Japan.”

Beyond the government, the announcement by the Japanese trading house Itochu in early 2024 that it would end cooperation with Israeli defense company Elbit Systems was, according to Reuters, due in part to the World Court’s January 2024 ruling against Israel.

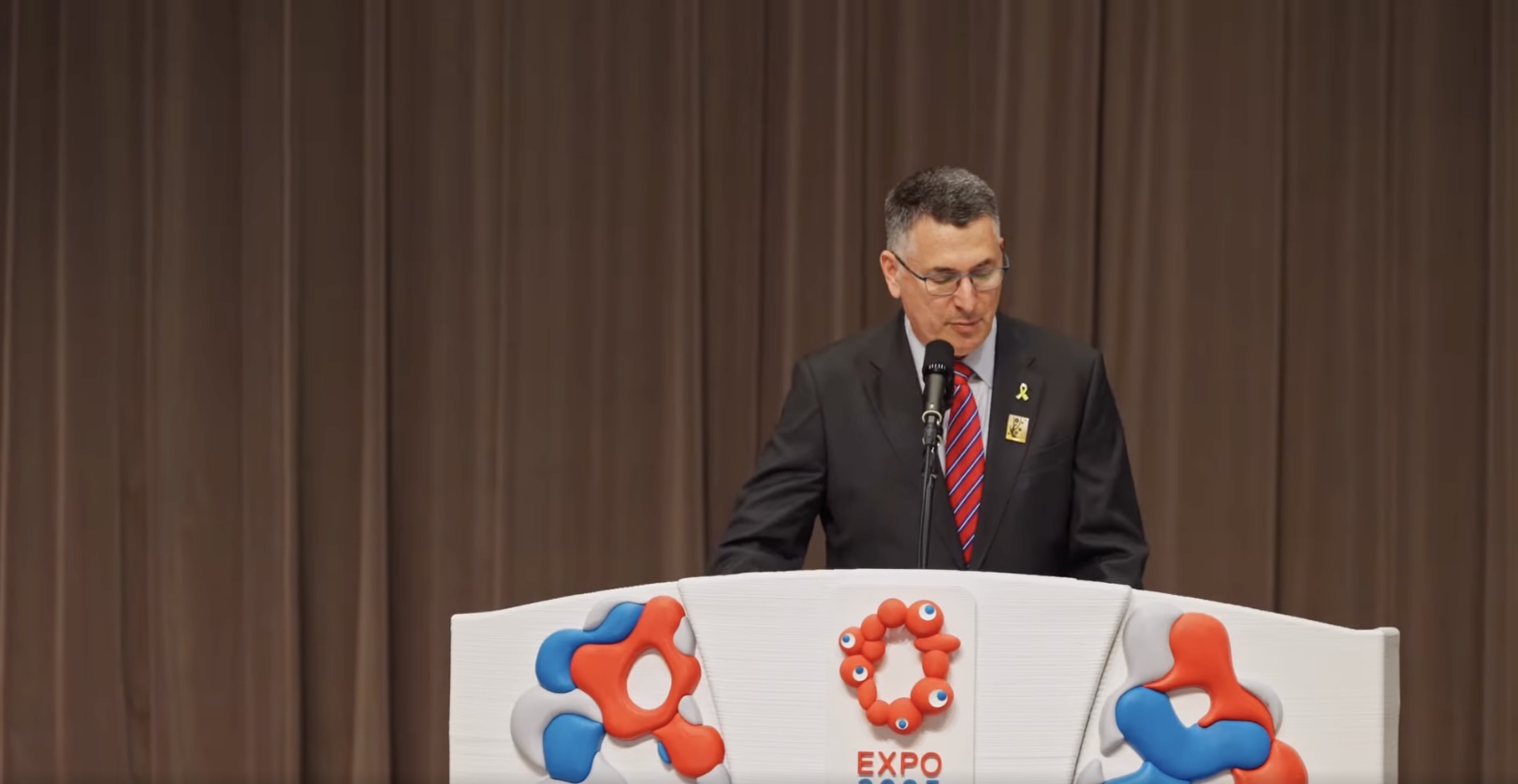

Israel has appeared eager to maintain ties with Japan. This year, a high-level delegation led by Sa’ar (the first by an Israeli foreign minister in 15 years), visited Tokyo and Israel’s Expo booth. The visit, the Times of Israel reported, was intended to “strengthen Israel’s narrative in the Japanese press” according to Sa’ar’s office. Sa’ar’s visit prompted protests outside his press conference in Tokyo.

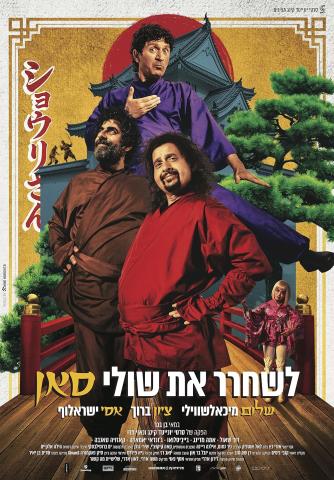

Reinforcing Ikegami’s point that Japan is popular among Israelis, this July saw the premiere of Saving Shuli-san, an Israeli action-comedy production filmed on location in Japan. The film, according to promotional material, is about “three friends on a chaotic mission to save their wannabe-chef nephew, who’s gotten a little too close to the yakuza! Expect ninjas, Mount Fuji, Kabukicho, sexy chaos, and a very foreigner-fueled version of Nippon”. The film has become the fifth most viewed Israeli film of all time, according to the Times of Israel.

While Ihiba’s administration sometimes offered harsh words for Israel and joined multilateral diplomatic efforts, such as a UK-led effort this July to condemning what was called Israel’s “drip feeding of aid and the inhumane killing of civilians”, that approach could change under the new administration of Sanae Takaichi.

Takaichi has made no secret of her admiration for Abe and support for his economic and security policies, but whether she will continue Abe’s engagement with Israel remains to be seen. However, pro-Israel voices in Japan have celebrated Takaichi’s appointment as prime minister. And for good reason: during the campaign for the LDP leadership election in September, all five candidates expressed agreement with the U.S.’s decision not to recognize Palestinian statehood.

Today, there appears to be a growing distance between Japan’s government and public opinion regarding Israel. What this portends for the future of Israeli-Japanese cultural, diplomatic, and economic ties is, at this stage, difficult to predict.

Dylan O’Brien is a PhD Candidate in Cultural Anthropology at the University of California, San Diego. His research examines how representations of Jews and Judaism in Japan interact with Jews living in Japan.