Issue:

November 2025 | Cover story

Japan’s fraying coexistence with nature is fuelling an alarming surge in bear attacks, with deaths hitting a new record

The hot summer this year once again witnessed a surge in fatal bear attacks across Japan. In early July, 81-year-old Takahashi Seiko was found dead in her kitchen, her body marked by deep claw wounds. Having lived alone in her Iwate Prefecture village since her husband moved to a senior home a year earlier, she became the season’s first victim. Days later, in neighboring Fukushima Prefecture, 52-year-old Sato Kenju was mauled and dragged into the bushes, where his body was discovered hours later. In Hokkaido, a hunter went missing in an area where a brown bear had recently been sighted. Then, in August, a hiker in his 20s was attacked by a brown bear on a trail in the same prefecture and later died from his injuries in hospital. As autumn began, the death toll continued to rise alarmingly. In early October, an elderly man and a woman were killed by a black bear while picking mushrooms, one in Iwate and the other in Miyagi, while in Nagano Prefecture, the body of a 78-year-old man bearing multiple claw marks was discovered. Yet the number of fatalities kept climbing throughout October, reaching unprecedented levels and turning the wave of attacks into a national sensation.

A record year for bear-related fatalities

By October 30, the toll for fiscal year of 2025 (beginning April 1) had risen to at least 12 confirmed dead and nearly 200 injured – the highest fatality count in a century. These figures, double the previous annual record of fatalities since statistics began, underscore both the growing risk posed by Japan’s expanding bear populations and the broader challenges of managing them. At stake are not only environmental concerns but also social and cultural ones. In recent years, a fear of bears has resurfaced in Japan with renewed intensity. The year 2023 set a record with nearly 20,000 reported sightings – about 5,000 more than the year before. Even more troubling was the sharp rise in bear attacks on humans: 198 in total, six of them fatal, making it the deadliest year in recent decades – until 2025. By contrast, 2024 saw roughly half as many cases, injuries, and deaths. Yet despite such fluctuations, as the data from 2025 demonstrates, the long-term trend is unmistakable: encounters between humans and bears are becoming both more frequent and more fatal.

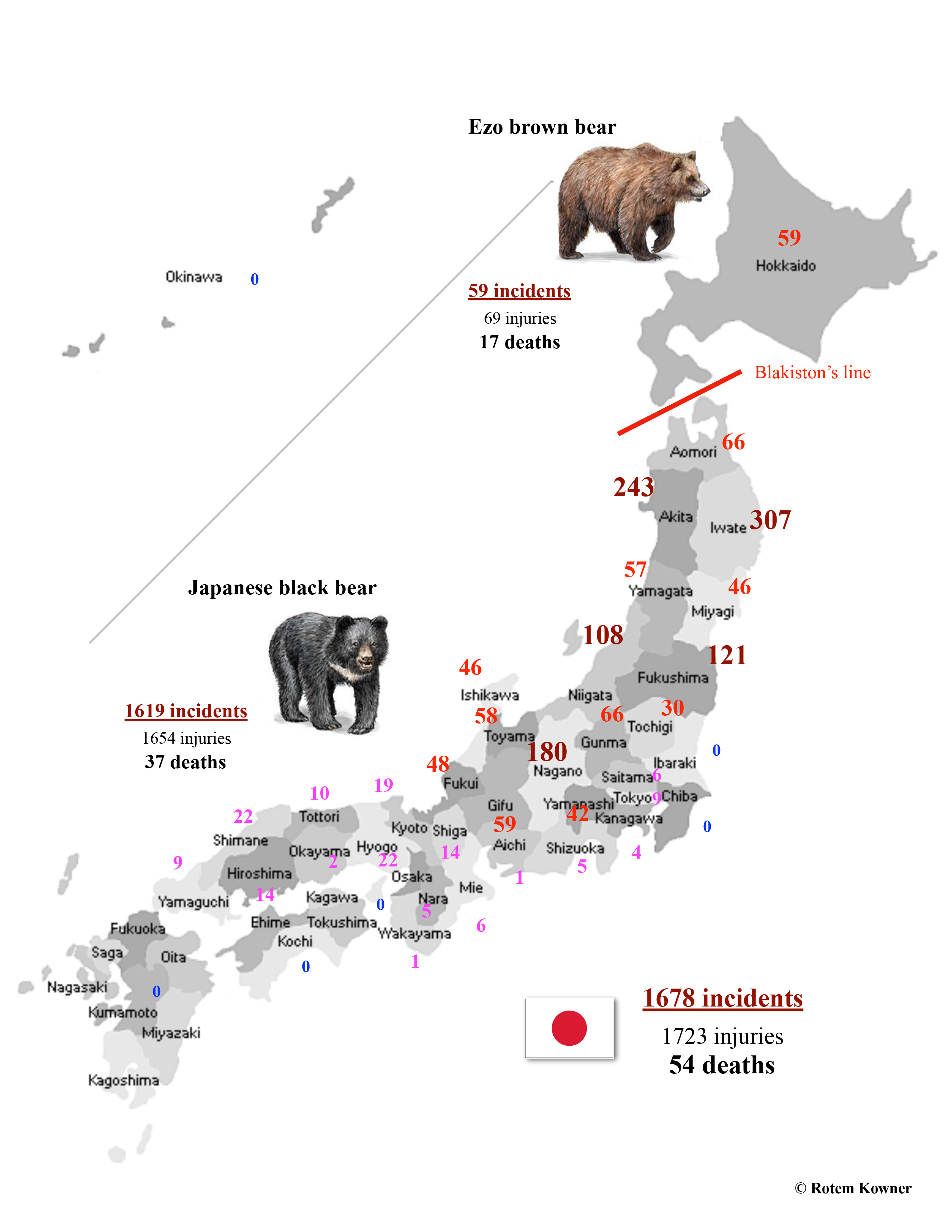

Between April 2008 and early October this year, Japan recorded no fewer than 1,678 bear attacks, resulting in 1,723 injuries and 54 deaths, 21 of them within the past three years (the number of confirmed deaths is current as of October 30). At first glance, this toll seems strikingly high. For comparison, across all of North America – where bears, including black, brown, and polar, are far more numerous – 65 people have been killed over the same 18-year period, only 12 during the past three years, and four in 2025. Yet perspective is essential. Hippopotamuses, for example, are estimated to kill about 500 people annually in Africa, while dog attacks in the United States alone claim 30 to 50 lives each year. While Japan is effectively free of rabies domestically, this disease, transmitted primarily through dog bites, remains far deadlier in other parts of the world. In 2024, India alone recorded an estimated 5-6,000 deaths from rabies.

Bear attacks, though rarely fatal, continue to grip the public imagination and dominate media coverage. As biologist Rami Reshef observes, the more violent and graphic an animal attack appears, the more it captures public attention, even when other threats prove vastly more lethal. This makes the question all the more pressing: how is Japan confronting the surge in bear encounters, and is a lasting remedy truly within reach?

Two species, two forms of attack

The story of Japan’s bears begins with basic zoology, yet it is their current patterns of attack that make this knowledge relevant today. The archipelago is home to two distinct species, each marked by its own habitat, physical traits, and behavioral tendencies, including characteristic forms of aggression toward humans. The Japanese black bear (tsukinowaguma), a subspecies of the Asian black bear, lives across most of Honshu, Japan’s largest island, along with a small, dwindling population around Mount Tsurugi in Shikoku. Relatively small to medium in size, the Japanese black bear is recognizable by the light crescent-shaped patch on its chest. Adult males typically weigh between 60 and 120 kilograms, while females are about half that, though rare specimens of over 200 kilograms have been documented. They prey on wild boar, serow, and sika deer, as well as invasive species such as nutria. But their diet also includes plants and seeds, allowing them to play a key role in maintaining ecological balance within their habitat.

Just 20 kilometers north of Honshu, across the Tsugaru Strait and the Blakiston’s Line – a famous faunal boundary – lies Japan’s northernmost main island of Hokkaido, home to the Ezo brown bear (higuma), also known as the Ussuri brown bear. Comparable in size and appearance to the North American grizzly, this formidable species stands as the apex of Japan's wildlife. Adult bears typically weigh between 200 and 300 kilograms, with the largest individuals exceeding 400 kilograms. Ecologically, this species plays a vital role, with an omnivore diet that spans small and large mammals, fish, birds, insects, and plants. Culturally, it has long held a central place for the Ainu people, the indigenous inhabitants of Hokkaido (formerly Ezo), Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands, who revered it as a divine being. In the ceremony known as iomante, the Ainu ritually sacrificed a bear cub, consuming its flesh and venerating it as a sacred offering from the bear god.

Which is more dangerous of the two? Surprisingly, and contrary to popular perception, it is actually the smaller black bear that proves more aggressive and less predictable.

This conclusion is made possible by the meticulous record-keeping of Japanese authorities, who document every incident and publish regular updates online. A comprehensive review of the full dataset from the past 18 years (2008–2025), conducted specifically for this article, reveals striking findings. Black bears were responsible for no less than 96.5% of all recorded attacks on humans and 96% of the injuries. In 2025 alone (as of October 6, with data tallied from April to March of the following year), they accounted for 95 of 99 bear attacks and 107 of 111 injuries. These figures reflect not only the species’ larger population (estimated at between 15,000 and 44,000, compared with less than 12,000 brown bears) and their greater proximity to human settlements, but also their heightened irritability and greater propensity to engage in violent encounters with people.

Even so, an encounter with a brown bear, rare as it may be, is far more likely to be fatal. Although this species accounts for only 17 of the 54 (31.5%) bear-related deaths recorded since 2008, and two out of 12 this year, the risk of not surviving such an encounter is more than 14 times higher than with a black bear. Specifically, while the probability of being injured in an attack by either species is roughly similar, 29% of brown bear attacks result in death, compared with only 2% of black bear attacks. This disparity reflects the brown bear’s much larger size, greater strength, and more aggressive defensive behavior once attacking, which make it vastly harder for humans to survive an encounter unscathed.

The geographic division into two species of bears and their distinct patterns of aggression strongly shape the geographic distribution of attacks in Japan. Over the past 18 years, the seven prefectures with the highest numbers of attacks and resulting injuries, all involving black bear, have been Iwate, Akita, Nagano, Fukushima, Niigata, Aomori, and Gunma. Concentrated either in the remote Tohoku region of northeast Honshu or the mountainous areas northwest of Tokyo, these prefectures alone account for no less than 64.5% of all recorded attacks. Hokkaido, by contrast, ranks only ninth in total attacks and injuries but, as expected, first in fatalities, with 17 deaths caused exclusively by brown bears (and 50 since 1962) – more than double the toll in the second-highest prefecture, Akita, which recorded eight. Black bears have on occasion attacked people even in urbanized prefectures such as Kyoto and Tokyo, though such incidents remain rare in cultivated lowland plains where bears cannot easily hide. No attacks, however, have been recorded in the islands of Kyushu, Shikoku, and Okinawa, nor in Honshu’s densely populated and relatively flat prefectures of Osaka, Chiba, and Ibaraki.

What should you do if such an encounter occurs? Japanese authorities advise avoiding eye contact with both brown and black bears, and never running away or turning your back. Both species are much faster than humans and are skilled climbers and swimmers, making escape nearly impossible; in fact, running may provoke a chase. With the smaller black bear, the recommended response is to stand tall, back away slowly, and, if attacked, fight back while making loud noises. A few Japanese have done so successfully: in 2003, a 63-year-old man used a judo throw against a bear that attacked him while mushroom picking in Nagano Prefecture; 13 years later, a karate black belt fended off a bear while fishing in Gunma Prefecture. Others, particularly the elderly or frail, have been less fortunate. Against a brown bear, martial arts are unlikely to work and may even further enrage the animal. In such cases, the best option is to lie face down, protect your head and neck with your arms, and remain still until the bear departs.

Echoes of history

The recent attacks have struck a raw nerve. The danger posed by bears has been recognized in Japan since prehistoric times, though public attention has ebbed and flowed. Yet no incident has matched the notoriety of the December 1915 tragedy in Sankebetsu, a remote village on the coast of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost main island. Over the course of six harrowing days, a massive brown bear rampaged through the settlement, killing seven residents and terrifying the community. The first encounter with this 380 kilogram, 2.7-meter-tall beast had occurred about a month earlier, when it attempted to break into a house but retreated at the sound of a horse’s panicked whinny. Soon after, two hunters summoned by the homeowner managed to surprise the bear during another intrusion, leaving behind clear traces of blood along its escape route.

Several weeks later, the bear returned to the village, and the brief sense of security was instantly replaced by deep fear. This time, it broke into a house, killed an infant, fatally injured another, and abducted the woman caring for them. Her remains were found the next day in the nearby forest. The hunters warned that the taste of human flesh would only encourage the bear to return, so dozens of armed guards were called to the village. That very evening, the bear indeed came back, causing such panic that only one of the guards managed to fire his weapon. Shortly afterward, the fleeing bear entered another nearby home, killing three small children and a pregnant woman along with her unborn child.

In the days that followed, the bear returned to the village several more times, prompting the organization of additional hunting parties. One hunter eventually tracked it through the snow, discovered it resting beneath an oak tree, and killed it with two rifle shots. Although the incident occurred 110 years ago, it has since become an inexhaustible source of retellings: inspiring literary works, a stage play, a feature film, and a range of scholarly studies. Later behavioral analyses suggested that the aggressive bear had woken too early from hibernation due to hunger. If this explanation is correct, its aggression was indirectly linked to human activity, as decades of intensive deforestation in the region, trees felled largely for drying fish, had severely damaged its natural habitat.

Zoologists also pointed out that the bear attacked humans only after being shot, though many local residents believed the bear was an oni (a demon in Japanese folklore) or a possessing spirit. They paid no heed to scholarly analyses, and in the years that followed, they abandoned their villages, leaving them as ghost settlements. Even if their beliefs seem unfounded and their fears exaggerated, the event in Sankebetsu shaped the attitudes of many Japanese toward bears and cemented a deep-seated fear of them.

The climate change factor

Today, bear attacks reinforce public anxieties rooted in the Sankebetsu Incident, but now with far greater reach and immediacy. Bears are highly visible in contemporary Japan – both in lived experience and, even more intensely, in the media. Regular news reports of fatal encounters are matched by warning placards scattered across nature reserves, forest trails, and tourist sites, cautioning visitors about recent activity. The anxiety spills into major cities as well: on the fringes of Kyoto and Sapporo, where urban neighborhoods meet steep, wooded slopes, warning signs are ubiquitous.

This growing presence has had a significant impact on public behavior. Out of fear of bears, many people avoid hiking in nature, especially alone, opting instead for brief visits to designated sites or spots within short walking distance from their cars. This anxiety is contagious, I have found. Recently, a bear was sighted near my own residence in the outskirts of Kyoto, and in light of the local chatter, I too have avoided walking on the street next to the forest after dark. Those who do venture out often carry a playing radio or small bells to signal their presence and avoid surprise encounters. Yet no evidence shows that bells actually reduce attacks; some even argue they may attract a bear’s curiosity while dulling the carrier’s ability to hear approaching animals. Bear spray, widely used in North America, is considered far more effective, though it remains uncommon in Japan.

The causes behind the recent surge in bear attacks are complex, but scholars widely agree that population growth is a central factor. Over the past three decades, Japan’s bear population has roughly doubled. Coupled with the effects of climate change, this growth has intensified competition for natural food sources and reduced their availability. As a result, bears are increasingly driven out of forests in search of food in open landscapes and even in populated areas. Fatal encounters between bears and humans typically occur along the margins where their respective habitats overlap. In these liminal zones, often on the edge of rural settlements, bears have begun to recognize that humans are not as threatening as they once were, and they now regard people not only as competitors for food but, at times, as potential prey.

Human demography is also a factor. While bear numbers are rising, the rural population in Japan’s frontier regions is steadily shrinking. In 1980, the agricultural workforce numbered about seven million people, roughly 150,000 of whom were employed in forestry and logging. Today, although Japan’s total population is larger, the number of farmers and forestry workers has dropped by nearly two-thirds. hundreds of villages, especially remote mountain settlements, have been almost entirely abandoned. In addition, the average age of residents in these rural settlements is particularly high, leaving them less physically active and making their responses to bear encounters less intimidating. It is no coincidence that many of the recent victims have been elderly individuals attacked on the fringes of their villages. However, the problem is no longer confined to the agricultural sector. Bears are now venturing into urban areas and attacking residents, as several recent fatal incidents in the city of Sapporo have shown. In addition, the growing presence of bears and the fear they inspire have caused many hikers to avoid nature altogether, reinforcing a trend that peaked during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The overall effect of bear attacks on tourism is still undocumented. On the one hand, the recent incidents cast a long shadow over tourism, both domestic and international. Repeated reports of fatal encounters discourage hikers, campers, and nature enthusiasts from venturing into forests and mountain trails, areas once central to Japan’s outdoor tourism industry. Domestic visitors often avoid rural attractions, undermining local economies already weakened by depopulation. International tourists, who are particularly sensitive to safety concerns, may reconsider trips to regions like Hokkaido or Tohoku, traditionally promoted for their wilderness appeal. As fear overshadows natural beauty, communities dependent on tourism suffer declining revenues, while Japan’s global image as a safe travel destination is subtly eroded.

On the other hand, some tourists are drawn to bears precisely because of their recent notoriety. Several “bear parks” now capitalize on Japan’s fascination with these animals, the most prominent being in Noboribetsu, Hokkaido, which houses some 70 brown bears, and in Okuhida, Gifu, home to more than 150 black bears. In both sites, the animals are kept in large concrete enclosures, where visitors are encouraged to buy processed food and toss it over the fence to waiting bears, who sit or stand in anticipation of being fed.

A visit to the Okuhida Bear Park begins in a gift shop filled with cuddly toy teddy bears alongside a counter selling small bottles of so-called “bear oil”. This traditional Chinese remedy is derived from the bile of black bears, typically extracted while they are confined to tiny cages – causing immense suffering and premature death. The method of producing this substance outside Japan has attracted widespread international criticism, and there are signs that the park is aware of the controversy. One vendor reassures curious visitors that the oil, also sold online, is obtained from a handful of bears hunted locally each year, not from the park itself, where the animals supposedly “die a natural death”. Yet most of the bears on display are conspicuously young. Signs on their enclosures list names and ages, revealing that the majority are around five years old or younger. This is puzzling, given that the park has been in operation for more than 40 years and that bears in captivity can easily live for 30 years or more.

Delicate ecological balance

Authorities themselves face limits with handling bear attacks. Culling is regularly carried out by licensed hunters, but their ranks have thinned dramatically. In 1975, Japan had over half a million hunters, fewer than one in 10 older than 60. By 2020 the number had shrunk to 218,500, nearly six in 10 past that age – an aging, dwindling force that mirrors the country’s own demographics. Moreover, until very recently, hunters could only shoot an attacking bear after securing police authorization, a restriction that helps explain why the unprecedented culling of 1,804 brown bears in fiscal 2023 did little to reduce incidents. On February 21, 2025, However, Japan passed a bill permitting the immediate culling of bears in urban areas during emergencies. Alongside this measure, some organizations have been established to monitor populations and develop defensive tools, though their presence varies widely across prefectures. In the meantime, local authorities have opted for less lethal deterrents, ranging from electric fences, wolf-shaped scarecrow robots with glowing red eyes to drones and even an artificial intelligence–based alert system.

Bear attacks have also become a prominent theme in the media, with every fatal incident receiving wide coverage. Domestic outlets, from newspapers to television news, frequently emphasize dramatic encounters, fatalities, and community anxieties, often providing detailed accounts of affected prefectures and local safety measures—reporting that at times amplifies the sense of danger. Yet few present the problem as a national crisis requiring urgent action, perhaps because the vast majority of the attacks occur in remote rural areas, particularly in the poor and sparsely populated Tohoku region, which together with Hokkaido accounts for 85% of all fatalities. International media, by contrast, typically situate the problem within broader frameworks such as conservation, climate change, and global human–wildlife conflict. What both perspectives often neglect, however, are statistical context, long-term ecological policy, and the lived voices of rural communities.

Indeed, the ursine problem in contemporary Japan carries both practical and symbolic weight. The spread of bears, alongside other wildlife, reflects yet another stage in the gradual retreat of humans from agriculture and nature into urban centers – a trend especially pronounced in countries with shrinking populations such as Japan. At the same time, fear of bears risks provoking overreactions and even their eradication from vast areas, with potentially severe consequences for ecological balance. Japan needs its bears, for they remain the country’s only large predators. Wolves once roamed Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu but were exterminated by the early 20th century. Other carnivores – foxes, raccoon dogs (tanuki), and martens – are widespread, but they are mid-sized predators rather than “large” ones and cannot control large herbivores.

Overall, there is no quick remedy for these complex challenges - that includes the recent request by the governor of Akita prefecture for help from the Ground Self-Defense Forces, who are legally not permitted to shoot bears. Instead, what is required is a gradual readjustment and the careful development of a new modus vivendi that respects both humans and animals. This will involve not only short-term safety measures but also long-term ecological planning that recognizes the role of bears within Japan’s ecosystems. As an advanced society, Japan must now strike a delicate balance. The outcome will determine whether coexistence remains possible, or whether fear and overreaction will tip the scales toward ecological impoverishment.

Rotem Kowner is a historian and professor of Japanese Studies at the University of Haifa, Israel, with research interests that include Japan's environmental issues. His recently published book is titled A Hardening Hierarchy: The Japanese in the Global Formation of Racial Ideologies, 1735–1854 (McGill-Queen’s University Press).