Issue:

December 2025

How a lovestruck female arsonist ignited centuries of superstition in Japan

In Tokyo's Shinagawa Ward, a small triangle of greenery forms a “V” between National Highway 1 and a section of the old Tokaido that from feudal times linked Edo with Kyoto. This is all that remains of Suzugamori, one of Edo's three main execution grounds. In its heyday, Suzugamori’s area measured about the size of a football pitch.

The site, well maintained by the neighboring Daikyoji temple, is identified by signs as a historic landmark. Among the relics on display are two square stone slabs, measuring slightly less than one meter on each side. The one on the right has a circular hole to support a wooden post used for hi-aburi (burning at the stake). Its companion has a square hole, which supported the crossbeams used for haritsuke, a gory form of execution involving perforation with spears.

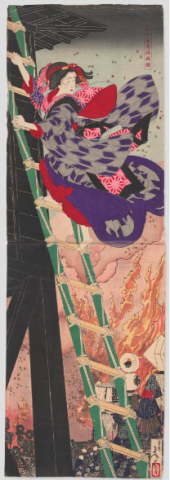

With closely concentrated neighborhoods built of wood and paper, Edo and other cities were tinderboxes, especially on dry winter nights when winds blew strongly. Most fires were accidental, but in cases when an arsonist was apprehended, the prescribed punishment was burning at the stake.

These tasks were entrusted to hinin (literally "non-humans"), as society's outcasts were so termed. They would secure the condemned to the stake with hands bound behind their backs. A framework of bamboo strips was looped around the stake to support the straw packed beside the condemned. Several bundles of firewood and more straw were placed at the foot of the stake. At the signal from the presiding official, several hinin carrying tapers would set the structure ablaze.

Old records show that the hinin were also responsible for procuring the rope, straw, firewood and other materials, for which they submitted an itemized bill to the city authorities.

Some references indicate that the condemned were put to death before the fire was ignited, and this may well have been the case for some. Other accounts, however, recorded that screams were audible as far as eight kilometers away.

As with other forms of the death penalty, further “punishment” was meted out post mortem. What remained of the corpse was left at the stake for two nights and three days, with a placard posted giving the name of the criminal and details of his or her offense. Scavengers paid nocturnal visits to nibble on the charred remains.

This form of punishment was one of the first to be abolished under the new Meiji government in 1869. In 1683, however, the penalty was very much in practice.

Which brings us to the famous tale of the teenage firebug known as Yaoya no Oshichi. She was the daughter of a dispossessed samurai who became a greengrocer in Komagome. When a fire broke out at the end of 1682, Oshichi and her family evacuated to temporary quarters at Enjoji, the family's temple. There she caught the eye of a novice priest, and romance blossomed.

Thinking perhaps that another fire in the neighborhood would allow her to enjoy a repeat encounter with her cloistered lover, she attempted to set fire to her own house, but was caught red-handed and charged with arson. Having not yet turned 16, Oshichi should have been tried as a juvenile, which would have reduced her sentence by one degree to permanent exile on one of the Izu islands. As the story goes, the lovestruck teenager, deciding that death would be preferable to permanent separation from her beloved, inflated her age by one year and suffered the consequences.

Justice came swiftly. On the 27th day of the third month of 1683, she and five other arsonists were bound, set atop horses, and led in a hikimawashi procession to Kanda, Asakusa, Yotsuya, Shiba and Nihombashi. A sympathetic bystander is said to have thrust a sprig of late-blooming cherry blossoms into her hand, one of the many romantic stories spun following her death. Her execution at Suzugamori came two days later.

And the novice priest? Whether out of deep remorse or simply in shock over the whole affair, he took vows of celibacy. In one version, he became a wandering mendicant, erecting Jizo statues at roadsides. His surname was never really ascertained: Some versions give it as Onogawa, others as Ikuta and still others as Yamada.

Researchers point out various other inconsistencies to the tale. While popular writer Ihara Saikaku and others stated that Oshichi was 16 years old, the math doesn't fit as if she had been born in 1666 (a hinoeuma year) she would have been 18 years old in 1683, the year of her execution. This calculation, however, is contradicted by a plaque posted by Oshichi at the Yanaka Kan'oji Temple in 1676, which stated she was 11 years old, which would have meant her birth year was indeed 1666.

Oshichi's enduring renown must be credited to sensational coverage in kawara-ban (Edo’s rudimentary news sheets) and Saikaku's 1686 work Koshoku Gonin Onna (Five Women Who Loved Love), which appeared three years after Oshichi's death.

Saikaku not only spins a good story, but concludes his tales with sensible, if somewhat ironic, advice: "In this world we cannot afford to be careless. When traveling keep ... money ... out of sight. Do not display your knife to a drunkard, and don’t show your daughter to a monk, even if he seems to have given up the world."

The Heibonsha Encyclopedia cites an old document as saying: Hinoeuma no toshi ni umareta onna wa kanarazu otoko wo tabeheru to yo ni tsutaheshi (It is popularly said that a woman born in the fire-horse year will be certain to consume a man).

The superstition took root around the mid-Edo period, at which time novels and ema (votive tablets) contained passages suggesting that hinoeuma years saw a rise in cases of child abandonment and infanticide.

According to a September 25 article in the Mainichi Shimbun, a decline in birth rates could be statistically confirmed from the late Edo period, during the hinoeuma year of 1846.

Based on data from the Civil Register and Family Table compiled by the Meiji government, the number of births in 1846 was estimated to be more than 10% lower than the preceding and following years, with fewer females registered than males.

In the modern era, the superstition was kept alive by authors and dramatists, the best known being Natsume Soseki. In his 1907 novel The Poppy, Soseki describes a femme fatale named Fujio, who bewitches her male paramour, as "having been born in a fire-horse year”.

During the Taisho era (1912-1926), suicides were reported by women born in the hinoeuma year 1906 as they reached marriageable age and despaired over their future. The Asahi Shimbun of May 9, 1927, reported that the previous day, the body of a young woman had been found in Enoshima, Kanagawa Prefecture, bearing a note that read, "I think hinoeuma is a superstition, but my misfortune is real."

The Japanese superstition may have tenuous links to Chinese prognostication, where hinoe is the positive of fire, indicating a rising, strong condition, while uma (horse) refers to south when applied to direction and noon for the time of day.

When the 10 heavenly stems and 12 earthly branches are combined with the philosophy of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements – which states that "all things are made up of the five elements of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water" – the idea that "fire" symbolizes the burning sun and flames and is explosive and difficult to control, and the Hour of the Horse, when the sun rises directly overhead, may underscore the belief that hinoeuma years are those having the strongest fire energy, with fire elements overlapping and disasters more likely to occur.

In China at the time, the hinoeuma years that occur in 60-year cycles were considered inauspicious mainly in terms of natural disasters, while in Japan, the notion spread among the hoi polloi that women born in a hinoeuma year were unlucky.

Now let's fast forward to New Year's Eve 1965, when your writer, age 18, was at the Tachikawa Air Base passenger terminal waiting for a Southern Air Transport flight to Kadena, Okinawa.

I had picked up the January 1 edition of the Japan Times, which was already on sale on the base, and on page 10 spotted the headline: "Some people superstitious about girls born in year of Hinoeuma being unlucky."

Hani wrote:

Though it was not recorded as an official statement at any medical meeting, some gynecologists of the nation openly talked of an alarming phenomenon last year – that abortion took a noticeable increase during the last half of 1965.

It was not that Japanese people's sex morals suddenly broke down. The cause was that some people here are still highly superstitious in this atomic and space age.

Superstition and abortion come together because 1966 is a specially inauspicious year for a girl to be born according to the sexagenary cycle of Chinese origin. Superstitious parents could not take the 50-50 chance that their offspring could be a boy, and chose to terminate the pregnancy.

Hani went on to cite that in 1905, the year before the previous hinoeuma year, 716,822 baby girls were born. In the hinoeuma year 1906, their numbers dropped to 668,140 and in 1907 the numbers recovered to 798,672.

Hani also noted that some parents may have juggled the figures by advancing or delaying the entry of their daughters' names into the family register, in an ex-post-facto attempt to remove the stigma attached to being born in an inauspicious year.

According to a government White Paper on Population released on December 25, 1965, a sharp drop had been observed in the number of marriages from April on, indicating efforts of some people to avoid giving birth in 1966.

Those predictions for a drop in births certainly came true: the number in 1966 was 1,369,740, considerably lower than the 1.82 million babies born the previous year and the 1.94 million born the following year. (A stock market crash in 1965 may have exacerbated the decline.)

Recalling Hani's predictions, I updated the story for Tokyo Journal magazine in 1987, which was the year hinoeuma-born children observed their coming of age.

When I asked a Japanese fortuneteller about the superstition, she informed me: "The part about killing their husband probably doesn't hold true. But the fact is that these women tend to have strong personalities. If they marry a weak man and come to dominate him, then there is bound to be disharmony. This is really what we try to caution young people about."

She added: "Many young people are curious about astrology, but the older people are the ones who view these things so seriously. The real opposition to a marriage is likely to come from the grandmother of the groom, who is probably old enough to remember all the troubles that happened to women born in 1906."

So now the immediate question arises, what's in store for Japan in 2026? Will the already historically low birth rate take an additional hit from this old wives' tale?

For all intents and purposes, it appears that today's Japanese have become pragmatic enough to have moved on to more rational concerns.

Last June, Josei Seven magazine pointed out that when the former Kiko Kawashima married Prince (presently Crown Prince) Akishino in 1990, the issue of her having been born in 1966 was not raised at all. "In other words," the writer concluded, "it's safe to say that the fire-horse superstition was already over at that point.”

Writing in the Mainichi Shimbun on September 25, Moe Yamamoto observed that "With the arrival of the Reiwa era, many people are unaware of this legend."

Yamamoto noted that this year's latest vital statistics released by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare show no evidence of an increase in births due to people bringing forward births. And perhaps more significantly, she wrote, "the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research's future population projections do not even factor in the influence of the hinoeuma”.

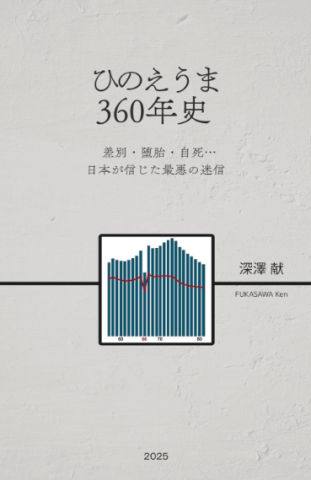

Last June, business journalist Ken Fukazawa, himself born in 1966, published an e-book titled A 360-Year History of Hinoeuma: Discrimination, Abortion, Suicide ... the Worst Superstition Believed in Japan, in which he proclaimed, "The hinoeuma superstition has gone to eternal rest."

Fukazawa points out that the superstition led to the sudden drop in births in 1966 because of society's gender role division of labor, which expected women to be "obedient”.

"The problem lies not with women born in hinoeuma years," he told the Mainichi, "but with the male-dominated society that has allowed discrimination based on birth to continue. Men are too unaware of the preferential treatment they have received from the powerful. I doubt that this has changed even today."

A translator, columnist and avid reader of mystery fiction, Mark Schreiber has lived in Tokyo since 1966, which he regards as a lucky year, at least for himself.