Issue:

Death in Kudan

The unexplained demise of a Reuters correspondent while in Kempeitai custody in 1940 is a reminder that Japan was not always a cozy assignment for journalists

By Mark Schreiber

At approximately 12:30 p.m. on July 29, 1940, Reuters correspondent Melville James Cox fell to his death from a fourth story window at Kempeitai (military police) headquarters in Kudan. The 55 year old Cox had been detained two days earlier, along with 10 other British nationals, for questioning on suspicion of espionage. His death, reported as a suicide in Japanese newspapers, was treated more suspiciously by the international press.

Tensions between Japan and Great Britain had been building from the previous January, when the British Royal Navy cruiser Liverpool halted the NYK passenger liner Asama Maru in international waters off the coast of Chiba, near the end of its voyage from San Francisco to Yokohama. An armed boarding party from the Liverpool took into custody 21 German passengers suspected of being German military personnel.

Japan was inching closer to an alliance with Germany with which Britain was already at war and for such an incident to occur adjacent to home waters infuriated the Japanese. Diplomacy prevailed, however: The British released nine of the detained Germans, and the Japanese government under Prime Minister Mitsumasa Yonai in turn agreed not to give passage on civilian ships to Germans of military age.

Japan at that time was well along in the process of secretly building up its fleet of capital ships, and the Kempeitai had been under heavy pressure from the navy to plug leaks about the refitting of the Nagato, a 32,200 ton battleship originally commissioned in 1920. The Kempeitai had been tailing Cox as a person of interest for three years, after intercepting a letter of uncertain origin that contained a passage in what appeared to be secret code.

In an article titled “The secret of Japan that I saw” in the Dec. 25, 1957 issue of Tokyo Shuho magazine, Hisashi Nemoto, a former Kempeitai captain who had been assigned to watch Cox and who personally witnessed much of what transpired gave his version of events. Nemoto wrote of the travails of his hardworking operatives, noting that they had trailed their subject to night clubs featuring “erotic performances.” The operatives also reported that “Cox often visits the Imperial Hotel, where he meets with various suspicious persons, both Japanese and foreign,” “He uses the post office inside the hotel to send mails” and “He always uses the same type of envelope when sending mail abroad.”

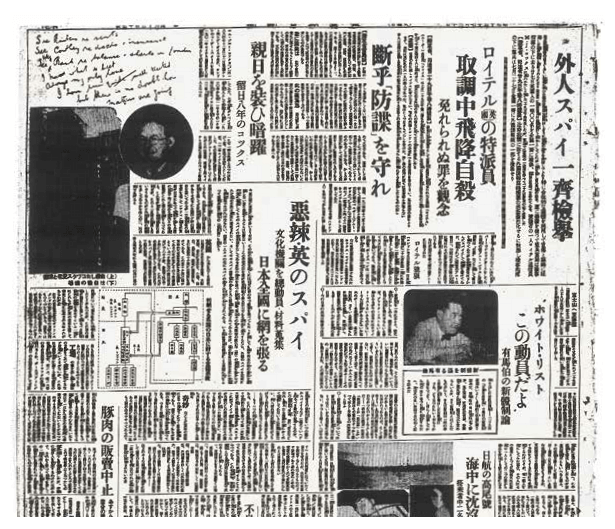

Cox’s note top left of this July 30, 1940, edition of the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun is reproduced opposite the headline, “Foreign spies arrested in simultaneous roundup,” above.

The Kempeitai also observed that Cox appeared to have formed a “close relationship” with an intelligence officer at the embassy of “a certain foreign country” and suspected he was able to prevail upon the diplomat to forward reports to intelligence agencies in the UK, a violation of Japan’s law regarding use of the telegraph.

IN LATE JULY, NEMOTO was dispatched to Cox’s residence in Chigasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture, to bring him back to Tokyo for questioning. He was accompanied by an English inter preter named Taguchi who had spent 20 years practicing law in the US. The group returned to Tokyo by train, and Cox spent the nights of the 27th and 28th sweltering in a tiny, airless cell in the basement of the Kempeitai subheadquarters in Kudan, not far from Yasukuni Shrine.

On the 29th, Cox underwent a third day of questioning in a room on the 4th floor. The police allowed him to receive a sashiire lunch of Western food delivered from outside, and after the meal he had been pacing inside the room when suddenly he made a dash for the open window.

As Nemoto relates, “Sgt. Kamata, who had been guarding the prisoner, rushed to stop him . . . grabbing Mr. Cox’s left foot with both hands. But he was already too late, as Cox’s entire body was outside the window, and in a flash his body fell from the fourth story window to the rear yard.”

Nemoto described Kamata’s face as “pallid” as he rushed into the former’s office and said, “Sir, we’ve got trouble! Cox has jumped. Come quick!” Irritated by the intrusion, Nemoto rushed to the window and looked out into the yard, to see Cox’s prostrate body.

The reporter was pronounced dead at 3:46 p.m. The timing was unfortunate in the extreme: Unbeknownst to the Kempeitai and Cox, Reuters had asked the Domei news agency to help secure his release and Inosuke Furuno, president of Domei, had been meeting with the War Minister at the time of his death.

A note was found on Cox’s person, apparently addressed to his wife, which the Japanese authorities claimed to be a “suicide note.” It read, “See Reuters re rents. See Cowley re deeds and insurance. . . . I know what is best always, my only love. I have been well treated but there is no doubt about how matters are going.”

REPORTER OR A SPY? AND WAS HE MURDERED OR DID HE DIE BY HIS OWN HAND?

In his work Britain & Japan Biographical Portraits, Sir Hugh Cortazzi, the late British Ambassador to Japan, included a report by the embassy on the incident. It stated that an American doctor who viewed the body noted that the injuries were such that they could be attributed to a fall from 40 feet, that there were no signs of prior physical ill treatment and that the body was found so far out from the building that it could be presumed that he leaped, disproving a fall from foul play. The British consul had examined the “suicide note,” which he believed was in Cox’s handwriting and had the impression that the correspondent was “sure gendarmerie intended to convict him by hook or by crook.

A FUNERAL WAS HELD for Cox at St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Shiba Park, with four Kempeitai officers, including Nemoto, in attendance. Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka, who had known Cox personally, made an ex gratia payment to his widow of ¥100,000, equivalent at the time to £5,833.68, and a considerable sum in those times.

The British government immediately retaliated against Japan for the arrests of its nationals, detaining the branch managers of the Mitsubishi and Mitsui trading firms in London, and eight others in the U.K. and several commonwealth cities, including Sydney and Hong Kong. (They were eventually all released unharmed.)

So what was Cox, a reporter or a spy? And was he murdered or did he die by his own hand?

Then British Ambassador to Japan Sir Robert Craigie refused to believe that Cox “could have been connected even remotely with espionage.” He was highly critical of Kempeitai interrogation techniques, noting that their “method of submitting the prisoner to long and intensive grilling lasting sometimes from 9 in the morning to 10 p.m. was of a character to test the strongest nerves and that it was a well known thing that in the case of someone of Cox’s disposition, intense depression was thus induced.”

Two weeks after Cox’s death, R. Selby Walker, the Reuters acting general manager for the Far East, who was resident in Shanghai, submitted a lengthy report to the company’s managing director in London. According to him, Cox had been receiving hints for some time that the authorities were after him because he knew and said too much about the activities of the Nazis and Japanese with pro Axis sympathies. He noted that an AP correspondent had been arrested and interrogated for five hours in connection with a telegram he’d sent about Cox’s arrest, and that he’d been left “so mentally battered and bruised that he could not think of anything but how to get away.” Walker also assumed that Cox took his own life, but that he’d been driven to it, and he believed that the report of the American doctor seemed to disprove any idea of murder.

Although Cox was popular among colleagues at the American Club for his “bright and cheery disposition,” Cortazzi noted that he “had been ‘making himself a nuisance at Gaimusho press briefings. He asked a barrage of awkward questions and made no effort to cover up his contempt and growing animosity for the Japanese militaristic state.’”

Punishments were meted out to at least two Kempeitai members responsible for Cox’s safety. As the officer in charge of the interrogation, Captain Nemoto was ordered confined to his barracks and received a punitive wage cut. Sgt. Kamata was subjected to “administrative punishment” and reassigned overseas. Interestingly in 1948, Nemoto was sentenced to three and a half years imprisonment for his alleged involvement in the deaths of 17 U.S. air crew members shot down over Japan. Describing Cox’s death in the magazine article 17 years after the incident, when he was under no threat of prosecution or punishment, Nemoto maintained that no foul play had occurred.

Former Ambassador Cortazzi, who presumably had access to whatever evidence was available, eventually concluded that, “The true facts about how Cox died will probably never be known. . . . The Kempeitai had nothing to gain by his death except perhaps that in their interpretation it tended to confirm his guilt. . . . Whether it was suicide or not, it is clear that the Kempeitai behaved with brutality and inexcusable callousness.”

Mark Schreiber currently writes the “Big in Japan” and “Bilingual” columns for the Japan Times.