Issue:

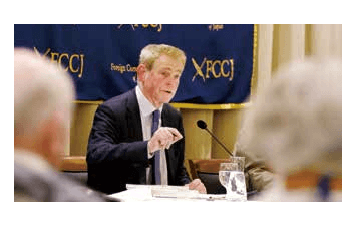

photo by ALBERT SIEGEL

In the line of fire

It’s open season on reporters worldwide, laments the author of a guidebook on journalists’ safety.

By David McNeill

WHEN JARROD RAMOS BLASTED five people to death in the newsroom of the Capital Gazette in Annapolis, Maryland last June, it was another grim marker in a bloody period of violence against media workers.

The Committee to Protect Journalists lists 44 reporters killed worldwide this year, including Jamal Khashoggi, reportedly lynched inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul by assassins armed with syringes and cutting tools. While well below the 155 deaths recorded in 2006 (at the height of the chaotic Iraq War), the number is deceptive: Instead of dying in crossfire, journalists are increasingly being targeted just for the work they do.

“Killings, attacks and jailings of journalists worldwide are at an all time high,” says William Horsley, author of the Safety of Journalists Guidebook. Thanks partly to the rise of illiberal governments, he says, many people now speak of “open season” on reporters.

Horsley says the state of the media is an “absolutely crucial warning” of when things go wrong in society, and is “very intimately tied to structures of power,” noting mounting hostility to the media, from China to Europe and even the United States.

For journalists, he says, the most dangerous development in this trend is the fusing of partisan politics with media power. In many places, the media have become a tool of ruling parties, “with ruthless domination of the information sphere through technology, violence and the misuse of law.”

The template is China, where the ruling party keeps its hands around the throat of old media, while jailing bloggers and using monitoring systems and firewalls to control cyberspace. In Russia, media watchdog Reporters Without Borders recently noted the “steady decline in media pluralism” and growing control of media outlets, which are used to “inundate the public with propaganda.” Then there are European countries in the grip of various shades of authoritarianism, including Hungary, Poland and Turkey.

Paradoxically, says Horsley, the framework of legal protections for media workers has never been stronger. But more countries are flouting these protections. Even countries like Britain, which helped create the system on which the free press has been built, seem determined to pull it down, he says, noting, for example, the way the current British government has insulted and vilified the European court.

THE SPEED OF DECLINE in media freedom has been striking, he says. “The surprise has been that state power has been so adept and quick at using software to track and monitor its enemies, and create armies of trolls to frighten and intimidate people, and buy up more and more of the media landscape.”

Even more worrying, he says, has been the growing hostility to independent journalism in the citadels of advanced liberal capitalism. Horsley describes Donald Trump’s media baiting as “a torpedo” fired right at the heart of America’s First Amendment, which protects freedom of speech.

“The demonization of journalists and the vilification of journalism is seen by many as incitement to violence and hatred,” he says. Though America still has some of the strongest media protections in the world, the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker website notes over 40 major physical assaults on journalists in 2018.

In August, outgoing United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad al Hussein didn’t mince words when he said that Trump’s rhetoric “echoed that of the worst eras of the 20th century.” Says Horsley: “Is this not incitement to violence against the press coming from the president of the United States himself? And it is giving cover to other countries that abuse journalists.”

The rise of Trumpism shouldn’t surprise too much: The Republican Party helped pave the way when it scrapped the media fairness doctrine in 1987. “Given that, and the turbo charging provided by the internet, it was only a matter of time before the American media landscape lost its key distinction between fact and comment and its attachment to facts and standards.” But given the robustness of the American system, he says, critical journalism will survive there.

As for Japan, which Horsley spent over seven years covering as the BBC’s bureau chief in the 1980s, he believes the practice of critical journalism, never particularly robust, is being weakened. “Compare it to countries that do have a free press and you see the enormous difference. The expectations and behavior of Japanese journalists are so much more conditioned by their relations with sources and the government. There is little real narrative of fighting for press freedom, and against abuse. There are flashes here and there, but the overall record is not at all clear.”

The bright spot, he says, is that you often find the “spunkiest journalists” in the most troubled spots. Sometimes we are at our best when things are at their worst.

*Safety of Journalists Guidebook is published by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, an intergovernmental body of 57 participating states with a mandate that includes fair elections, human rights and freedom of the press.

David McNeill writes for the Irish Times and the Economist and teaches media and politics at Hosei University.