Issue:

An Italian documentary team tries to grasp the scope of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and finds a society undergoing drastic transformation while accepting the direction of Party leadership.

By Pio d’Emilia

“Let China sleep, for when she awakes, she will shake the world.” Used and abused as it has been, this phrase of Napoleon’s though very likely wrongly attributed to him still resonates. For China has awakened, and is indeed shaking the world. Not violently, as other fast growing, hegemonic powers have done. Instead, it seems, the centuries of ups and downs, natural and human provoked catastrophies, aggressions and exploitations, invasions and occupations have taught the Chinese a lesson: economic and cultural pressure is much more effective in conquering and much more important in maintaining power.

As millions of Americans and Europeans grew up with Rambo and other Western icons, hundreds of millions of Chinese now revere Jin Wu, hero of the blockbuster series Senrou (“Wolf warriors”). Cute, just and generous, he shows up in timely fashion in locations all over the world to protect and save Chinese citizens and Chinese interests. But this guardian never champions revolutionaries, insurgents or freedom fighters in struggles against bloody regimes or arrogant and corrupt dictatorships. No. He always sides with the establishment, protecting the status quo.

And here’s why. China’s relentless transformation of the production processes from sweatshops and intensive labor factories to international financial and third sector services and technological hubs is bringing along in its wake a massive social mutation. The Chinese middle class is becoming something like a new, internationalized bourgeoisie aristocracy, proud and self confident, at times even arrogant, and very far from Westerners’ expectations. Instead of feeding a desire for democracy and undermining the establishment, it cements the support for the regime, perceived as the source of security, stability, order and growth.

In other words, do not expect a former Soviet Union like collapse, nor another Tiananmen. When Chinese dream about their future, they don’t dream about the Dalai Lama’s return, free and “democratic” elections, self determination or the end of the brutal repression of ethnic and religious minorities. They dream about when they will be able to buy and live in a big apartment in a high rise, something that hundreds of million citizens have already achieved, despite the ever rising prices. In big cities like Shanghai the cost for one square meter in a high rise may go up to US$40,000, making a mansion in Ginza a real bargain.

This is what dictators love and Western powers never understood: just feed the establishment, and let people decide what to do with their “dear” leaders. The rest of us had now better learn to get it right. Or we may all end up like the Blade Runner replicant Roy Batty, talking about “things you humans could never believe.” After a few months of reporting in and on China, riding trains, driving on highways, witnessing the immense, apparently inexhaustible energy and optimism, I do believe.

This is it. China is taking over.

The future is here

Ever since I devoured colleague and former Guardian Tokyo correspondent Jonathan Watts’ marvelous book, When a Billion Chinese Jump, I’ve dreamt of some how doing the same thing, but with a camera. Every body knows at least a little about what is going on in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and eastern China. But very few know about the interior of the country, north and especially northwest. This is where the Dragon’s awakening is at its most fast and furious: 30,000 kilometers of high speed railroads (and another 20,000 to come in the next ten years); over five million kilometers of highways; 800 million people shifted from poverty into middle class with 700 million expected to travel abroad in the next few years.

What is happening in China is already affecting the whole world, and the Belt & Road Initiative, whether you like it or not, is poised to make history. The so called new Marshall Plan, already worth more than a trillion US dollars and very likely to double by the year 2050 is not only going to expand China’s commercial, financial and political tentacles over Central Asia, Europe, Africa and probably South America, it is going to change China herself. Make no mistake, though: While it is possible that economic progress and social development may bring a new consciousness, a new approach to civil freedoms and human rights, I find it doubtful that it will destroy, or even reduce, the crucial, central role of the Communist Party. Applications to join, which were declining until Deng Xiaoping’s new “Great Leap Forward,” are now increasing yearly. Over 20 million applied last year, of which less than 2 million were accepted (and these are subject to revision within the first two years).

For years I tried to convince my editors to invest in coverage of this story, and eventually I succeeded. Supported by a decent budget and, most important, the full confidence and trust of my editors, on April 4 we started our journey. After a few days in Beijing to organize things, we set off for Chongqing. Still relatively unknown abroad, Chongqing has in the last few years become the largest megalopolis in the planet. We arrived there at night, by air, and I am still mesmerized by what we saw on our visit. Blade Runner, if I may make another reference to that film. Or Hayao Miyazaki’s fantasy world in Spirited Away, since many people seem to believe he got his inspiration for the magical bathhouse from a popular restaurant here, and the resemblance is striking.

THE REST OF US HAD NOW BETTER LEARN TO GET IT RIGHT.

THIS IS IT. CHINA IS TAKING OVER.

To say Chongqing is booming is a ridiculous under statement. The greater metropolitan area has already reached 40 million inhabitants. There are 77 universities, over a thousand public hospitals and three different urban “people movers,” moving sidewalks that carry people at two speeds over 12 kilometers. But the city is also becoming with new, strict rules about construction and environmental issues the symbol of a historical switch from the country’s long and disastrous war against nature to a new era of sustainable growth. No nation has ever challenged mother nature mostly disastrously as China has from ancient times. But authorities now seem to view nature not as an enemy to subdue, but a precious ally.

Top to bottom: Shooting at clouds at the Weather Modification Agency; A hard fought for shot of sunset at the border; With Zhang Duo, the young, proud director of Horgos Railway Station.

Smooth roads hit a rough spot

Travelling through China with an improvised and somewhat anarchic TV crew was easier than expected. The Chinese Embassy in Rome issued us multiple three month visas (for non resident journalists) without setting limitations or conditions on our reporting, other than requesting a very rough itinerary and a list of the public and strategic places we wanted to shoot. Over almost two months of travelling back and forth over the main “silk” railroads that connect China and Europe, we were never stopped, bothered, or asked to show footage. We even changed our schedule several times, causing lots of trouble, yet received no avoiding warnings.

With one exception: Xinjiang, the autonomous region where a conflict with local Muslims is ongoing. We had come from Lanzhou in Gansu Province, where we had been the first foreign TV crew allowed to shoot inside the Weather Modification Agency, which shoots at clouds to make them rain. Arriving in Urumqi felt like a different country, maybe a less polite North Korea. From the very moment we checked into our bizarre hotel, the Yema Desert Silk Road (where, thanks to a hypervisionary, billionaire owner, the room fee included a ride on one of the hundreds of horses who are fed and coddled there) until we left the region one week later, we were constantly followed by at least two “minders” who were supposed to “help” us but who did their best to make our journey a real nightmare.

Not even in my trips to North Korea have I had to negotiate for each single, innocuous shot. At one point, we were taken into custody by the police because we were doing some “unauthorized” shooting of the main road from our car, and they managed to keep us detained for hours, with our “helpers” unable to explain who we were and why we were shooting. The odd and unpleasant situation was finally solved by diplomatic authorities, after our helpers proved helpless. Note that we were not trying to shoot anything “sensitive.” We were not looking for dissident Uighurs willing to speak about the recent violence and roundups. From the very beginning of our trip we decided to stay out of trouble in order to finish our project without any problems.

And so we had, carefully avoiding any kind of potentially risky location or situation. But we couldn’t help, in this huge, beautiful ocean of land in Urumqi and the rest of Xinjiang, to feel as if the constant and pervasive tension could detonate at any moment. There’s no doubt this is their most sensitive, most difficult to handle local challenge, and while the Chinese government is handling it with overpowering determination, it could get out of hand at any moment.

Actually, we also had lots of fun. Our hardest and most absurd negotiation took place on the very last day. We needed to shoot a nice sunset, and for various reasons, we had not yet been able to get one. All day, we’d been shooting trains crossing the border in Horgos, the last town before Kazakhstan, and we asked the station master to please allow us in again, in the evening, to film the sunset. The young and sharp Mr. Zhang, a 23 year old naval engineer from Chengdu who had ended up managing a train station “in the heart of history,” as he proudly and repeatedly put it, immediately said yes. Only to be harshly reprimanded by another Mr. Zhang, our young and arrogant “government team” leader, who bluntly refused the request.

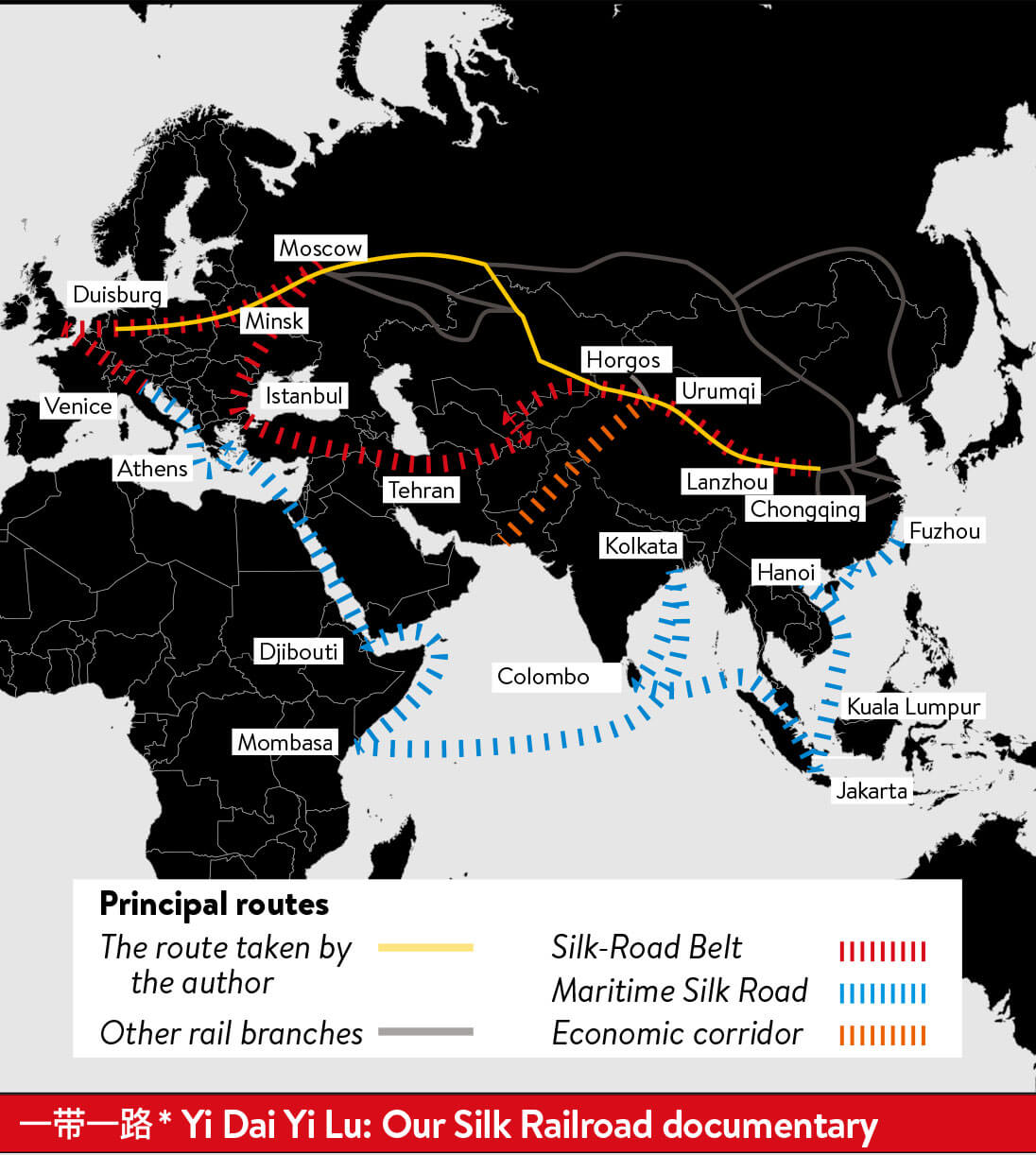

SINCE THE FIRST ONE left the station in 2013, more than 10,000 “China Express” trains have made the passage between China and Europe, a journey that covers about 11,000 kilometers in 17 to 19 days. Most of them end up in Duisburg, Germany, but there are now a total of 15 direct destinations in Europe, and more are to be added in the next years. We started reporting from Chong Qing, where we were able to film loading operations; on average, every day a train of 50 cars departs the station for Europe

More than 10 stations, including Chengdu, Lanzhou, Xi’an and Senzhou, are seeing off China Express trains, most of which pass through Horgos or Alashanko, in Xinjiang, where after a time wasting and costly transfer onto a larger gauge track they enter Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland and, eventually, Germany, which is where our reporting ended after almost two months. Although there are hundreds of handlers, logistic and loading companies involved, China Railways, a public company, is directly managing the entire operation, which for the time being and at least until the end of 2020 is heavily subsidized by the Chinese government.

While most trains travel fully loaded from China, on their way back the average rate is about 30 percent of their capacity. This trend is slowly improving, but it will take a few years until European companies may find out the land/rail transportation could be a good alternative to sea freight, at least for certain products.

One Belt, One Road

“This is not in your shooting list,” said the latter Zhang. “It is very late, and we have organized a dinner for you, and you should not get too tired, since you must leave tomorrow.” “Your thoughtfulness is appreciated,” we replied, “but still . . . we do want to shoot the sunset.” And, believe it or not, we spent the next couple of hours getting everyone from the Italian Embassy in Beijing, the Chinese Foreign Ministry and the Xinjiang Autonomous Province International Public Relations office involved. But the answer was still no, we were told.

We were almost going to give up, forfeiting dinner and the formal greetings, when I realized that our presence there was far from welcomed, mainly because the whole government team was obliged to follow us instead of enjoying what was actually a long period of holidays. So I said: “Sorry, but this is very important for us. And since I understand this must be taken to higher level, which will probably take time, this being a period of public holidays, after all, we are going to wait here until the problem is solved. After all, our visas don’t expire for 10 days, so we will just relax and stroll around. But you don’t have to accompany us, of course. We’ll manage on our own.”

A few minutes later, we had their permission. And, in the end, they became thoroughly involved in taking selfies with the wonderful sunset, apparently surprised that even the border could offer a romantic side.

Welcome to the Party

Eventually we left China in a good mood. What we were able to see over our long journey on the “silk trains” (although it’s likely they carry everything except silk) could not be dampened by the heavy handed Xinjiang way of dealing with their local conflict. And I now actually believe it is time to avoid the “yes, but” approach, and learn from Chinese pragmatism. Every country, every society has corpses in their closet, old and new. To different degrees, we in America, Europe and Japan still have to clean up our past and present misdeeds. China’s astonishing performance and achievements cannot be blurred by continuing to denounce the invasion of Tibet, the cruel treat ment of some religious and ethnic minorities and the ongoing, blatant violation of human rights. The “yes, but” approach, if applied to Italy, for example, could very well translate into: “Yes we have a full fledged democracy, freedom of speech and free elections . . . but one third of the population lives below the poverty level, and it is going to get worse”.

At the risk of being repetitive, I believe the new emerging leading class made up of engineers, researchers, managers and financial wizards is not going to challenge the “system” because they are not against the Party. On the contrary, they are grateful. Despite what we usually read and hear from Western “experts,

At the risk of being repetitive, I believe the new emerging leading class made up of engineers, researchers, managers and financial wizards is not going to challenge the “system” because they are not against the Party. On the contrary, they are grateful. Despite what we usually read and hear from Western “experts,” in China we won’t witness anything close to Gorbachev’s glasnost and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union Empire. More competition, market economy and globalization and the undeniable social development that result are not challenging the role of the Party and its leaders. On the contrary, they have given them the future.

Pio d’Emilia is the East Asia Correspondent for Italy’s Sky TG24.