Issue:

How a chance call to Nagoya and an aversion to tatami mats led to a major change in Australia’s China policy.

by GREGORY CLARK

My scoop begins back in the cold, wet spring of 1971. The world table tennis championships were underway in Nagoya, when we discovered that all the participating teams were invited to visit China after the tournament. Even the Americans have been invited. But the Australians, it seems, have been ignored.

I urgently set out to contact Dr. John Jackson, the Australian team manager, whom my office finds visiting a factory outside Nagoya. When asked why the team won’t be going to China, Jackson simply says that for some reason there was no invite for the Australian team. In any case, he says, his team had already planned on more training in Japan, followed by a visit to Taiwan.

I assume that Australia has been ignored because its anti Beijing policies are even more strident than Washington’s. Still, I suggest he call me if he visits Tokyo.

A week later he rings, asking for help with a place to stay. I give him a ryokan address, but an hour later he calls back. They are insisting he has to sleep on straw mats. He wants a hotel, he says, not a horse stable.

It is early evening, and finding somewhere cheap to stay in Tokyo on a rainy night will not be easy. Reluctantly, I say he and the team member traveling with him can stay at my place. I’ll let them use my bed in the bedroom, and I will sleep on straw mats in the tatami room.

Over the next few days, we meet occasionally over breakfast. Four days later, I tell him what a pity it was he did not get the invitation to go to China, and pass him that morning’s Japan Times. Splashed across the front page is a photo of the U.S. team in Beijing, shaking hands with Premier Zhou Enlai in the Great Hall of the People. He and his team could have been part of the global sensation, I tell him.

HIS EYES NARROW. “TO tell the truth, Greg,” he says, “we were invited to China. But the Australian government insisted that we visit Taiwan after Nagoya. They even organized the visas for us.”

I ask if he would like to go to China and be famous. He agrees, and I head to the local post office to send a cable in his name to the Beijing sports authorities saying he now wants to accept their earlier invitation. I add a request for permission for one journalist, Gregory Clark, to cover the visit.

Beijing replies immediately with an invitation, and Clark is invited to come along. But there are problems facing Dr. Jackson: one, much of his team has scattered; two, while there are members still training in Tokyo, he doesn’t know how to contact them; and three, even if he puts a team together, they have no money to get to the Hong Kong and Lo Wu border post the only entry point to China.

A frantic telephone search of Tokyo’s dingy training halls finds three team members. With Jackson and his friend that makes five; hopefully enough of a “team” to warrant a Chinese welcome.

In deep secrecy, I tell my newspaper, the Australian, that if they can cough up the fares to Hong Kong for our “team,” I can deliver a worldshattering scoop or, at least, an Australia shattering one. Sydney comes back very quickly saying yes.

But the three players we tracked down want to continue training in Japan, and are reluctant to go to China. Then I remember that Japan’s table tennis association chief, Ichiro Ogimura, is famous for all he has done to promote sporting ties with China. I contact him and he agrees to push the Australian players into stopping their training, and make the trip. One remains adamantly opposed, so I find myself a mere 24 hours later heading for Hong Kong with my now four member team.

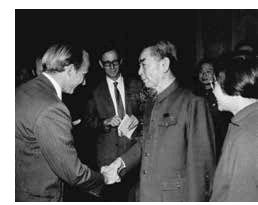

The author meets Premier Zhou Enlai.

THE NEXT MORNING, THE group, which includes myself and another Australian journalist from the very conservative, anti communist Melbourne Herald, are standing at the Lo Wu crossing, waiting to get into China. He, rather than someone from the less rightwing Sydney based Fairfax group, has been invited because Melbourne hosts the miniscule pro Beijing faction of the miniscule Australian Communist Party.

But for some reason, after handing over our documents, we find ourselves standing for hours in the hot sun at the Lo Wu frontier. Eventually a stern faced guard emerges to tell us that we cannot enter China because the players all have unused Taiwanese visas in their passports. And I have a used visa from Taiwan.

I insist that our mission is important for China and the world, and after numerous calls back and forth with the responsible Hong Kong office, we are finally allowed to board the one daily train to Guangzhou. My relief is considerable.

At Guangzhou we are met by a small delegation of boiler plate communist officials. Fortunately, it includes Mr. Yu a youngish, sophisticated official sent down from Beijing by the Chinese Foreign Ministry to look after us. He takes us to the famous Dongfang Hotel the city’s main hotel for welcoming foreign guests. But our euphoria is brief: we find that Beijing has not yet organized our press accreditation cards. So if I want to cable the story my newspaper wants so badly “First Australian Journalist into China since 1949” it will cost one U.S. dollar a word, and I have to pay before midnight.

Lacking funds for an in depth report, all I can do is file a brief story saying that we are all in China, and that the first breach in the wall of traditional Australian hostility to China has been made. The Herald man is much more aggressive. He sends a 3,000 word opus on the welcome we have been receiving that the girls look nice beneath their Mao costumes, that the food is splendid and the beer tastes good.

Unfortunately, he does not have the $3,000 needed to send all this back to Melbourne. He tells the cable office he will pay later, and heads for the room that we are sharing. We are both exhausted. I have hardly slept for three days.

AT EXACTLY MIDNIGHT, NOT long after we’ve stretched out in the sticky south China heat, there is a frantic knocking at the door. We open it to find that a group of angry young radicals want to know why the Herald man has not paid his cable bill.

Since my colleague does not speak Chinese, I try to explain. I also tell them that Chairman Mao has instructed young radicals to serve the people, and they clearly are not doing anything to serve my prostrate colleague. The radicals are not impressed, and march out swearing vengeance.

At breakfast the next morning the meet-and-greet friend liness of the night before has evaporated. I am now being viewed with intense loathing and silence by the staff, and when Mr. Yu shows up, the radical students are with him. Mr. Yu is looking very worried. He takes me aside and tells me that the young radicals had come to him, demanding my immediate expulsion from China for unacceptable behavior particularly the defamation of Chairman Mao.

Only after six hours of all night debate was he finally able to persuade the fanatics to allow me to stay on one condition: that I must make an apology. I take stock for a moment. I have spent years learning Chinese and studying China’s policies without prejudice. I have defied my own government and single handedly organized the skeleton of a ping pong team that Beijing wants so badly to visit.

And when I finally get to China, I discover that there are some people here who want me expelled on my very first evening. So I stomach my pride and do what Mr. Yu says; I am allowed to stay.

After an exhibition match in Guangzhou we head for Shanghai. Mr. Yu interrupts yet another boring ping pong marathon, saying he has some good news. A fellow Australian journalist will be joining us from Tokyo.

It is a Mr. Ssss . . . (Yu’s Shanghai accent is not helping). But he needs say no more since I have already guessed that Mr. Sss . . . is Max Suich, the Fairfax man in Tokyo. The highly competitive Suich has been on the phone to Beijing daily, demanding a visa. Beijing has relented, but only after a week of constant calls (as I am told later by the FCCJ front desk).

WHEN SUICH DOES GET the visa, he flies direct to Beijing, arriving a day before us. He even tries to scoop me. He sends off a story telling the world that he is the first Australian journalist to arrive in the Chinese capital since the 1949 revolution.

Upon arrival in Beijing, we are given the welcome usually reserved for potentates from friendly African countries. There is a large official banquet, and the next day we are taken to the Great Hall of the People to meet none other than Premier Zhou Enlai.

I still have a photo of the head of the Australian ping pong “team” being welcomed by the prime minister of the world’s largest nation. I also have a rather faded photo of myself meeting Zhou. He is looking straight at me. I am bowing slightly, Japanese style. I come away from the meeting with two lasting impressions. One is that there are cracks in the hastily built Great Hall. The other is Zhou’s extraordinarily magnetic presence.

Ping pong matches over, Suich and I ask for a formal briefing on China Australia relations, at which we are told that Canberra’s hostile attitude to China could lead to a major reduction in wheat purchases from Australia.

Our reports create a furor back in Ozland, and encourage the head of the opposition Labor party, Gough Whitlam, to visit China at the moment Henry Kissinger is making his secret visit on behalf of the U.S. President Nixon. The kudos helps Whitlam storm to victory at the next election in 1972, immediately giving Beijing the official recognition it wants.

A perfect example of scoop power!

Gregory Clark was Tokyo Bureau chief for the Australian, 1969-74, and is now a frequent contributor to the Japan Times. www.gregoryclark.net

We invite other journalists to share accounts of your scoops with our readers. Email the editors at no.1shimbun@fccj.or.jp