Issue:

BOOK REVIEW

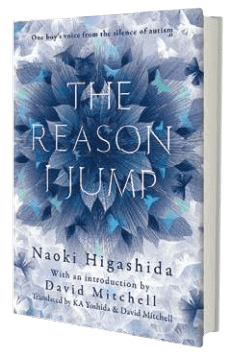

The Reason I Jump

by Naoki Higashida

Translated by KA Yoshida and David Mitchell (135pp. Random House)

reviewed by Tyler Rothmar

Just two days after the popular host of “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart” raved about the English translation of The Reason I Jump a book on autism written by a 13 year old Japanese boy it had soared to number one on Amazon.com.

The book was introduced on the show by the guest, Cloud Atlas author David Mitchell, who with his wife translated this rewarding little book and penned its foreward, and whose young son, like Higashida, is autistic.

Although Higashida is now 21 and a public speaker and author, when he wrote the original Japanese language edition of the book at the age of 13, he joined the ranks of Temple Grandin, Carly Fleischmann and others as a kind of embedded correspondent reporting from the trenches of the disorder. In the form of answers to 58 questions, interspersed with short stories and musings, the author attempts to explain his condition, to be understood and to improve the quality of life for people with autism and those who care for them.

Throughout the book, Higashida speaks both for himself and for autistic people interchangeably. This is understandable, given his age, but the assumption that his experiences of autism are shared by all autistic people is worth questioning, especially given the wide array of symptoms the disorder presents. As Mitchell noted in his “Daily Show” appearance, it’s probably better to speak in terms of “autisms,” rather than the singular, so varied and mysterious is the disorder. The other side of that coin is the idea that people with autism are fundamentally different from those without it.

Yet it is that very assumption that makes this book such a worthwhile read. The attempt to elucidate the differences unearths universal human experience. As he struggles with his autism and fights to interact with a world run by non-autistic people, the young Higashida marvels at the rest of us: “You normal people, you talk at an incredible speed. Between thinking something in your head and saying it takes you just a split second. To us, that’s like magic!” And fair enough.

In his descriptions of the beauty of nature, however, and his experience of time, Higashida unwittingly dusts off unimagined common ground. Evoking religious and mystical tones, he writes, “Just by looking at nature, I feel as if I’m being swallowed up into it, and in that moment I get the sensation that my body’s now a speck, a speck from long before I was born, a speck that is melting into nature herself. This sensation is so amazing that I forget that I’m a human being, and one with special needs to boot.”

In another section on being immersed in water, Higashida voices a sentiment to which many divers and swimmers can relate: “It’s so quiet and I’m so free and happy there. Nobody hassles us in the water, and it’s as if we’ve got all the time in the world. Whether we stay in one place or whether we’re swimming about, when we’re in the water we can really be at one with the pulse of time. Outside of the water there’s always too much stimulation for our eyes and our ears, and it’s impossible for us to guess how long one second is or how long an hour takes.”

Where the isolation and stigmatization that mark the disorder often result in autistic people being thought of as another category, Higashida’s writing clearly situates them on a spectrum, albeit at the far end, of the human experience. Reading his words, one is left with the notion that we’re all subject to the peculiarities of our own grey matter and the myriad nuances and differences in perception that entails.

That said, the daily battle of living with autism is dealt with plainly. “Whenever we’ve done something wrong, we get told off or laughed at, without even being able to apologize, and we end up hating ourselves and despairing about our own lives, again and again and again. It’s impossible not to wonder why we were born into this world as human beings at all,” he writes.

The horror of being trapped in a body that won’t obey, the paralysis of trying to keep up with life among the non-autistic and the shame and despair of disappointing loved ones run through the work like a pulse, always accompanied by a constant reminder, a plea, not to give up on autistic people.

In that Higashida casts light on some of autism's stranger traits, giving an insider perspective on sensory perception, feelings, panic attacks, numbers, schedules and language, the book is an indispensable aid for people who live or work with others who have the disorder.

Beyond that though, it is a thoroughly engaging read in and of itself. With disarmingly simple turns of phrase, Naoki Higashida, writing at the age of 13 with help by pointing at a chart of the Japanese alphabet, deals with joy and despair, wonder and death and the pith of what it is to be alive in the tradition of the finest writers.

Tyler Rothmar is an editor and writer based in Tokyo.