Issue:

May 2023

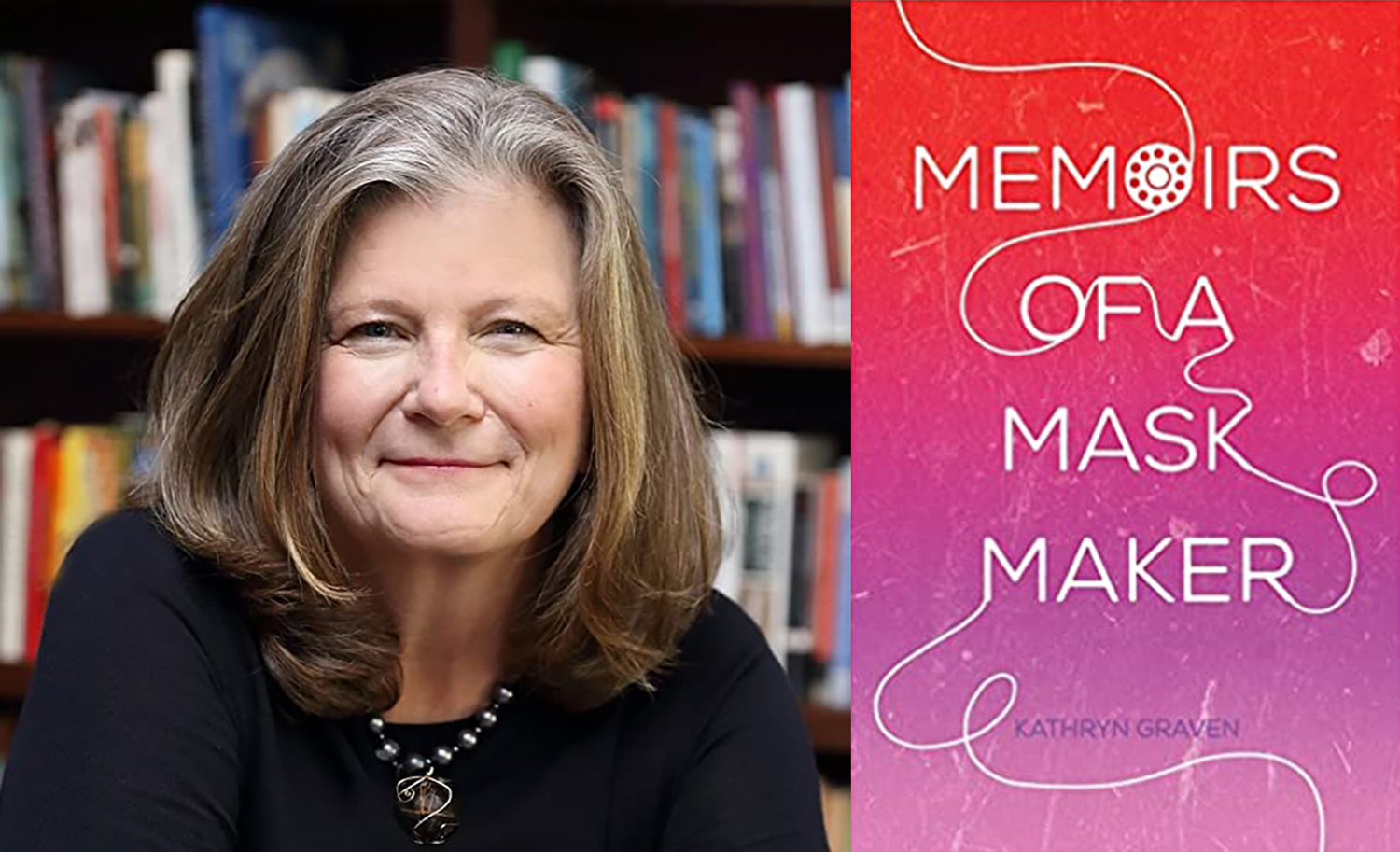

Kathryn Graven recalls her early relationship with newspapers and her career as a journalist in Tokyo in these edited extracts from her new book

Precariously perched on my bike, I peered into PO Box 8022. This was my window on the world beyond college life at Stanford University. Five days a week, I had mail. PO Box 8022 was stuffed with my personal subscription to the Wall Street Journal. Despite our rocky summer together, Dad had thought about how we could stay connected. The subscription was his idea, a college send-off present. New clothes, fresh sheets and towels for the dorm? Any of those would have been appropriate and practical. But as we know from my welcome home squid, my father did not do appropriate, or practical. I grabbed the newspaper, hoping to find a letter from friends in Japan or my various families tucked in the roll. Sometimes I did. But day in and day out during college, the reliable, steady news I received was business and economic.

Seeing the folded newspaper always reminded me of Dad’s dirty fingers. First thing every morning, he bounded down the stairs, opened the front door and plucked the Minneapolis Tribune from the brick steps. He made coffee and returned to bed with the newspaper. He emerged only after he had finished his morning read. He was oblivious to his messy ten digits, so newspaper ink was a breakfast staple: his thumbprint on a toasted English muffin, or on the white shell of a two-minute soft-boiled egg served in an egg cup. Dad ended his work day with a similar ritual. Returning home from his law office, he poured a glass of Scotch, snatched a handful of crackers, and sat down with the Minneapolis Star, the evening paper. Again, he never noticed the news ink transferred to the Triscuits or smeared on the orange Wisconsin cheddar cheese cubes he loved so much. News was all important: keeping current on local and national politics and, on Mondays, reading about his beloved Minnesota Vikings.

Dad did not just scour newspapers to keep himself informed. He wanted to review and discuss the day’s news at dinner. The more heated the debate, the better. For a while, I dodged questions about President Lyndon Johnson and the Vietnam War, because I was the youngest, only eight years old. But after my brother and sister both left for college, there was no place to hide at the table. Tricky, unscrupulous President Nixon and the unfolding Watergate scandal flavored my dinners as a 12-year-old.

On most days I tossed the Journal into my backpack and rode into the fray of White Plaza knowing I would never read beyond page one. I was happily immersed in the exotic machinations of ancient Japanese literature, world religions, and modern European history, not to mention the excitement of dorm life. The stock market held no appeal. In time, I skimmed the headlines, just in case Dad called. I wanted him to think I was staying current. But I hadn’t taken economics yet, and wasn’t interested in business, so a full read of the Journal was a stretch. There is no doubt Dad thought that the Journal subscription would help us transcend the turbulence in our relationship that reared in the summer and only increased after that ….

Riding Tokyo’s overcrowded subways, foreigners can’t help but stand out in the sea of black-haired commuters. On the Toyoko Line, which I took to work every day, I befriended another blonde American who got off one stop before me. He worked for ABC News. Comparing jobs, I calculated that he won, hands down, for more exciting job and career. When my friend informed me that he was leaving Japan, I applied to be his replacement.

The night editor’s shift from 4 p.m. to midnight was a serious step down in pay and lousy hours, my father duly noted. It was hardly glamorous to spend evenings alone, ripping sheets off the AP and UPI wire services, and watching Japanese news broadcasts. But it was a genuine job in a news bureau, and when the bureau chief offered it to me, I was thrilled.

During the day, before I reported to my night shift job at ABC News, I poked around for ways to break into print journalism. That’s the advice I was picking up from people who worked in the bureau and in the foreign press corps. Most reporters started off in print: wire service jobs led to newspapers, or maybe a national news weekly. Becoming an on-air television reporter was a remote possibility. People told me to write what I knew. From my stint at First Boston, I knew about Japanese banks and brokerage firms, and international financial markets. I pitched a story to the American Banker newspaper in New York.

I experienced my first byline joy when the Banker ran my story on nascent credit card use in Japan. Equally exciting, the editor asked how soon I could deliver another story. Japanese banking could be my beat, I thought optimistically. This coincided with big news events in Asia that unfolded on my watch on the night desk: Corazon Aquino rose to the presidency of the Philippines after the assassination of her husband, Benigno Aquino. In India, a trusted Sikh bodyguard assassinated Prime Minister Indira Ghandi. Several months later, pro-democracy leader Kim Dae Jung returned to South Korea from exile in the U.S. The political turnovers, filled with both pain and promise, sucked me in. I didn’t want to just read about current events, I wanted to cover them. I had no experience covering breaking news, but decided not to let that deter me.

I had, in fact, been a keen follower of Japanese news since my first year at the Ohtwara Girls High School. I dashed to the third-floor library during study hall, nabbed the Japan Times from the news rack, and settled into a corner. My brief but regular dates with the largest English language newspaper in Japan were a legitimate escape from the constant Japanese static ringing in my ears. I was lost in Mori-sensei’s classical Japanese language class; Ban-sensei’s biology class also bewildered. Reading the news in English about President Jimmy Carter and U.S.-Japan trade disputes over beef and oranges, or about Japanese productivity and manufacturing successes, I processed the words in my “normal” brain. I learned about Japan’s rising role in the world economy from the devastation of World War II. It was intriguing, exciting, and as the headlines screamed, a “miracle.” For the first time – ever – I felt I was living in an exhilarating time and place.

Access to news in English helped me make sense of Japanese household life. I devoured food columns which detailed how to prepare local seasonal vegetables, such as daikon radishes, wild mushrooms, eggplant and sweet potatoes. These served as talking points with Obaachan in the kitchen after school. I struggled to comprehend the opaque maneuverings of the Liberal Democratic Party, which gave me plenty of fodder to discuss with Otōsan. Pushing the limits of my sports interests, I followed sumo wrestling tournaments and humored all of them with questions about the huge wrestlers’ eating habits. I never failed to glance at the television listings for upcoming movies in English.

At Stanford, I never considered writing for the Daily. My Journal subscription taught me that Dad’s love of news was a double-edged sword, one I couldn’t quite handle. Reading and analyzing current events gave us something to talk about, but the endless unfolding also made it possible for us never to talk about other things: family cracks, personal hurts, underlying grief.

Back in Japan for the second time, I saw things differently. Once again, I picked up journals like the one Phyllis had given me, and took notes. I loved observing Japanese culture, sorting it out through writing. I didn’t equate writing in my journals, making notes on everything people did and said in Japan, with news until I started working at ABC. I had a sense I was in the right place at the right time with the right skills. What might have been an esoteric language skill now positioned me to do exciting work. To be 25 years old, fluent in Japanese, living and working in Tokyo in 1985 was not so wild a dream after all.

Witnessing unfolding events has the bizarre effect of hooking reporters into making awkward cold calls to complete strangers to ask deeply personal questions. Figuring out how to turn a vague outline of events into a compelling new story then becomes an urgent necessity. Tight deadlines add to the pressure. Why does anyone do this? There are as many answers as journalists, but for me, it was the challenge of overcoming my worst deficits: discombobulation, self-absorption and procrastination. Looking for the key details, listening to others, writing on deadline – those would be good skills to have – in English or Japanese.

Generously, veteran American journalists in Tokyo helped me map a path. They warned of long hours, low pay and an absurd amount of fun. A correspondent for Business Week opened my eyes to a full scholarship possibility to attend Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. A special, little known program there, funded by the U.S.-Japan Friendship Commission, was looking for Japanese speakers who wanted to become journalists.

That was me.

It was so much easier returning to Tokyo, now a familiar city, for my third stint in Japan. I was slipping back into a culture that I knew, a network of Japanese friends through AFS, with the backing of a supportive Japanese family. Looking ahead to long weekends, holidays, or when I just needed a break from urban life, I knew I could hop the newly completed shinkansen line from Ueno to Nasushiobara and Otōsan would pick me up. In Japan, I felt the intangible connectivity of being“home”that eluded me in Minneapolis.

“Tadaima,” I’m home, is how I felt seeing Okaasan’s smile.

“Okaerinasai,” Okaasan replied, so pleased to have me back.

On a hot August day in 1986, I received my first assignment from my Tokyo bureau chief. Japanese companies were turning the global auto industry on its head, moving their manufacturing overseas, touting their streamlined supply chains and innovative designs. But in auto-obsessed Japan, it was still difficult and expensive to get a driver’s license. Why?

To find out, I traveled to Yonezawa, a mountain city 200 miles from Tokyo, to a residential driver’s education boot camp. The course lasted 17 days and 16 nights, but I spent just a few days observing student drivers, listening to the instructors who practiced and effused calm, with an occasional bout of barking.

My story began: “After an hour of driving in circles practicing right-hand turns, Tsuneyoshi Yagi is ready to change directions. Forty minutes later he almost has the hang of left-hand turns.” Not exactly earth-shattering. To my shock, the piece ran on page one in the middle column slot, called the A- head because of the shape of the headline.“In Japan, the Road to a Driver’s License is Uphill and Bumpy,” read the headline.

The bureau celebrated my first success over beer and yakitori in the pub located in the Nihon Keizai Building. It was a great start, but too soon to feel confident. Editors are always wondering what your next story will be. And the next one after.

In the late 1980s, Japan’s rising role in the world and its postwar economic strides were a compelling backdrop to any story. I wrote about American companies trying to get a toehold in the booming Japanese market. I went behind the facade of the obedient Japanese work force to uncover how illegal foreign workers were penetrating the cracks, taking jobs Japanese no longer wanted to do. I followed regulators trying to shape the Tokyo stock market into something other than an insider’s trading den. Hot on the money trail, I tracked the Nikkei stock index, to see where nouveau riche Japanese were investing their cash.

On several occasions, I had to interview my former boss at First Boston. He was not happy with my decision to leave the investment bank for ABC News and had sent me off with a memorable put-down: “So, I suppose you think you are going to be the next Barbara Walters.” Two years later when I called and identified myself as a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, his first response was dead silence. Then, he invited me to a fancy lunch at the Imperial Hotel.

More satisfying for me than financial topics were the personal stories. I sat with Japanese housewives, giving them the opportunity to speak about their hopes and dreams for women and family. Their stories revealed the long shadows cast by a work culture that valued company loyalty and long hours above all else. And I took my turn in the foreign press pool waiting for hours in the Imperial Household Agency briefing room, listening to earnest officials give non-informative details of the declining health of the Showa Emperor, Hirohito, until his death in 1989.

I worked 80-hour weeks, lived and breathed the stories, the deadlines, the rewrites, the 4 a.m. phone calls from editors across the world. It was exciting, demanding, all- out fun work. I was deep into global financial markets, international trade disputes, the machinations of the Japanese economy, the competitiveness of the Japanese auto industry. But what I enjoyed most were the quirky stories that spoke to how the Japanese thought about their culture.

“For Tetsuro Ozawa, daily life in Japan can be a real pain. Mr. Ozawa is forever bumping his head. He also has trouble scrunching his legs under dinner tables while sitting on the floor. He is more than six feet tall, 6-feet-1 in fact.”

That beginning to an April 1990 front page piece about how the Japanese were getting taller and what that meant in terms of their psyche, not to mention the changes in industrial design standards it necessitated, was a favorite. When I first pitched the story to my bureau chief, he balked. It couldn’t be true and there was no way to prove it, he argued. I knew it was true from my own experience. At five feet four inches tall, I sat in the back of my Japanese high school class because I was considered tall. My height stayed constant, but in 1990 riding the Tokyo subways to work, I noticed the adults towered over me. The Japanese government, it turned out, keeps meticulous measurements of all grade school students’ heights; the data backed me up.

I was often asked what was it like to be a woman reporter in Japan. People expected to hear how disadvantaged a woman must be in the Japanese workplace. Japanese women were, but I never felt disadvantaged. In most interviews, even with high-ranking Japanese executives, I was taken seriously as a journalist, not in small part because I arrived without an interpreter, ready to conduct the interview in Japanese. Inevitably, a conversation ensued about where I had learned the language. I explained that I had spent a year at a Japanese girls’ high school in Ohtawara, had lived with a Japanese family, studied Japanese intensively. Once I had demonstrated both my provincial Tochigi and urban Tokyo accents – we had broken the ice.

The biggest hurdles I faced came from Americans, not Japanese. Never having worked a full-time job in America, I didn’t know how to navigate the politics and personalities of the foreign desk, let alone the other sections of the paper. I was at the mercy of my Tokyo bureau chiefs, who, not surprisingly, had their own priorities and office politics. In theory, I had a mentor in the highest-ranking woman at the Journal and my foreign editor based in New York. She took me on as an intern and then hired me as a Tokyo correspondent. But there were workplace issues I could never discuss with her. Like when the chairman of Dow Jones came to Tokyo and the bureau chief insisted the entire office go out after work to show the boss Golden Gai, an area near Shinjuku famous after World War II for its houses of prostitution. By the 1980s, the tiny bars and narrow alleys of Golden Gai were still seedy, a home to strip clubs and karaoke clubs serving pricey drinks. However inappropriate the sex-club bar hopping, I never complained to the foreign editor in New York. How could I? She was married to the chairman. I chalked up such after-work demands as the price of working in an overseas bureau of a prestigious American newspaper.

The material in this extract is copyrighted and used with the permission of the author. To learn more about the book and where to buy it, please visit Graven’s website in English or Japanese: www.kathryngraven.com