Issue:

January 2026

Experts have questioned DNA tests used to convict American Chris Payne of sexual assault in Japan

On the night of February 8, 2020, Christopher Payne was arrested after falling asleep drunk in the entranceway to a residence in Yamanashi prefecture. The 29-year-old American had not caused any damage, and the property’s owners didn’t press charges, accepting his apology for a making a silly mistake while inebriated. Before he was released, Payne voluntarily provided the police with a DNA sample via an oral swab. He didn’t know it then, but Payne’s act of cooperation would change his life beyond recognition.

Six months later, Payne’s DNA was tested, showing potential matches with the suspected perpetrator of a sexual assault in Ichikawa, Chiba Prefecture, near where Payne was living at the time. A hooded, masked man had followed a young woman from the station shortly after midnight on July 12, 2018, and grabbed her from behind, saying he had a knife. He told the woman that he was Indian and named Masala. He continued to talk during the 10-minute assault. She told investigators that his perfect, unaccented speech convinced her he was Japanese. When the assault ended, the woman spat out his semen, went home, and repeatedly gargled before calling the police. Trace amounts of the semen, mixed with her own DNA were obtained from her mouth.

“I was working that night at Tokyo Fight Club, a sports bar in Shibuya,” Payne said in late November, speaking from the other side of the visiting room glass at Tokyo Detention House, where he is being held in solitary confinement. “When I worked the nightshift, I would get a few hours’ sleep in the breakroom, and then go to my day job at Sakura Exchange, a money exchange run by the same company that operated the bar.

“There was a record of me working that night, but the manager couldn’t remember what time I had left because it was years afterwards when he was questioned. It was the night of England versus Croatia in the World Cup. My outstanding memory of the night was a group of England fans singing. I asked the police to check the phone location data when I was arrested, as I’d sent lots of messages to my girlfriend and my cousin that night. If they’d done it at the time, it would have proved I was in Shibuya.”

On December 26, 2020, prosecutors showed the victim 20 photographs of dark-skinned, non-Japanese suspects (Payne has African-American and Greek heritage). She did not identify Payne, but said she had not had a clear view of her attacker’s face. Payne was arrested on November 25, 2021.

“I believe the victim was called in four or five times by prosecutors. Prosecutors’ questions aren’t disclosed, only the responses,” Payne said. “But she went from saying her attacker was Japanese to he was a foreigner. Then that he wore the kind of cologne that foreigners wear. I never wear cologne and when they searched my apartment and found none, that changed to him having a ‘foreign smell’. At trial, his Japanese had changed from being perfect to sounding like a foreigner’s.”

The crime and subsequent legal case have not only devastated the lives of Payne and the survivor of the sexual assault. His ordeal also calls into question whether lessons have been learned, particularly on the use of DNA as evidence, from the case of Iwao Hakamada, who spent nearly half a century on death row in Japan’s most infamous miscarriage of justice.

Before the trial, Payne and his court-appointed lawyers requested a more accurate DNA test, which prosecutors assigned to Professor Yoshihiro Yamada of Kanagawa Dental University. According to a judgment summary, the test results found that “the frequency of appearance for another person having the same DNA profile was calculated based on an African-American genetic frequency database, resulting in approximately one in 446 quadrillion”. Adjusted for what is known as allele dropout — a phenomenon where only one of the two copies of a gene is detected, generating the risk of false positives — the final probability was given as “approximately one in 264 billion”. This suggested that those were the odds of Payne not being the perpetrator.

Faced with apparently overwhelming DNA proof – but no other evidence – that Payne had committed the crime, his public defense team advised him to plead guilty to receive a shorter sentence and a transfer from solitary confinement to a regular cell. At this point, his ex-girlfriend’s family, convinced of his innocence, began looking for other lawyers.

“While Chris was dating our daughter, he would come on family trips with us, and we would sit up drinking and talking. He was extremely kind and respectful to everyone. He became like a son and even after my daughter and he split up, we stayed friends,” said Kouta Handa, who has since become one of Payne’s most vocal supporters.

“When I heard he had been arrested for a sex crime, I knew he would never do such a thing. On the other hand, I had great respect and gratitude toward the police and the legal system for protecting the public. I had studied law and wanted to be a lawyer. At that time, it was difficult to believe the justice system could make such a mistake.”

After being turned down by around 50 law firms, Handa found Innocence Project Japan, a team of lawyers specializing in miscarriages of justice, who took on Payne’s case pro bono. The lawyers flagged multiple issues with the DNA testing, including an additional mitochondrial test — generally regarded as more reliable in instances of degraded nuclear DNA samples, such as those from the sexual assault — which detected no trace of Payne. Despite a lack of other evidence, Payne was convicted of sexual assault in July 2024 and given eight years imprisonment with labor, the long sentence reflecting his unwillingness to plead guilty.

Yamada, the professor who carried out the prosecution DNA test, was given the Japanese Association of Criminology Award in November 2024. Contacted at his university by the No. 1 Shimbun and asked if his tests in more than 1,100 police investigations have ever identified a suspect as not being the perpetrator, he replied: “No, to my recollection, there haven’t been any where I concluded exclusion. There were cases where our conclusion was that testing couldn’t be done because of issues with the material.”

In the infamous Hakamada case, the former boxer was convicted of the 1966 robbery and murder of the manager of miso factory where he worked, as well as the murders of his wife and two children. Hakamada had confessed after 50 days of being beaten, deprived of water, sleep and access to a toilet, while being questioned for up to 16 hours at a time. He withdrew his confession before trial. The only physical evidence against him was a set of clothing found in a miso tank 14 months after the murders that had a bloodstain identified as type B, the same as Hakamada’s – and approximately 20% of Japan’s population.

Hakamada was sentenced to hang, but doubts about his conviction were widely enough known that successive justice ministers for decades refused to sign the execution order. More advanced DNA testing techniques were used in 2008 and 2011 on blood found on what was believed to be perpetrator’s T-shirt and showed no match with Hakamada. Defense and prosecution DNA experts took samples of Hakamada’s blood in March 2012 to confirm his DNA. Prosecutors continued to claim Hakamada was guilty after he was released in 2014 and withdrew their final appeal in October 2024.

Yamada was the retrial prosecution DNA expert who tested the bloodstain and then took a blood sample from Hakamada at the Tokyo Detention House. However, he stated afterwards that the bloodstain wasn’t sufficient for an accurate test: “Like in the Hakamada case, I said it couldn’t be done but the defense said it could.”

According to Kiyomi Tsunogae, a lawyer on Hakamada’s appeal who is now representing Payne, Yamada’s test did produce a result, which he subsequently withdrew.

“Yamada’s expert report was submitted before the closed hearing to request a retrial, with the judges, defense, and prosecution. It stated that on the most important point – a bloodstain on the right shoulder that was from someone other than Mr. Hakamada – there was a result. But during the witness examination he ended up saying, ‘My analysis cannot be trusted,’” said Tsunogae.

Pressed by the Number 1 Shimbun on whether he had concerns that none of his test results in more than 1,100 cases had ever pointed to a suspect’s innocence, Yamada said he always worked to the best of his abilities without preconceptions. “In this case [Payne’s] as well, I haven’t heard the details … All I know is that there was a foreign male suspect and a female victim, and the sample taken from the victim’s mouth … I didn’t collect it myself. The forensic science laboratory conducted the initial testing. I received the remaining sample from the court, analyzed it, and issued the result. So, I don’t know whether the foreign gentleman is the perpetrator or not.”

Yamada added that the reason the mitochondrial test had failed to produce a result was that the DNA in sperm is contained in the tail, which sometimes falls off when samples age.

Katsuya Honda, professor emeritus of the University of Tsukuba and defense DNA expert in the Hakamada appeal, said mitochondrial DNA was generally better preserved in samples, and expressed doubts about Yamada’s explanation.

“He seems to be desperately trying to come up with explanations that don’t add up. Basically, the mitochondrial DNA result didn’t give him the outcome he wanted, so he’s just inventing explanations to justify that,” Honda said. “And the worst part is that he says the opposite depending on the situation. In one case, he says mitochondrial DNA is well preserved and should appear. But if it doesn’t, he says, ‘Well, sometimes it doesn’t survive, so you can’t trust that result.’ If explanations change arbitrarily from case to case like that, it’s meaningless.”

Honda believes the issue – which helps explain the conviction rate of around 99.9% in trials in Japan – is systemic rather than the fault of individual ill-intentioned actors.

“Judges don’t try to make proper scientific judgments,” he said. “They just want to rubber stamp the prosecution’s position. There’s no culture of judges thinking independently and calmly. If they rule in line with the prosecution, their careers advance. It’s effectively one side versus two – the judge and prosecutor together. The prosecution gets a free pass, while everything the defense says is dismissed, even when it’s correct.

“Japan’s system is completely out of step with international standards. And it doesn’t just affect Japanese people. Foreigners in Japan are subjected to the same treatment, just like in this case.”

After Payne’s conviction, his defense team consulted Dr. Simon Ford, a US-based forensic DNA consultant who has worked on thousands of cases. Ford identified further issues with the analysis and asked for the disclosure of Yamada’s raw data, a first in a Japanese criminal case.

“When I looked at the electropherogram charts in Yamada's report, I could tell that they had been altered in some way. The peaks that were showing up as being bona fide had been manipulated at some level. He had overridden some of the values and changed some of the values,” said Ford via Zoom. “That concerned me – it's something you would never see in the U.S. maybe partly because the underlying electronic data files are routinely disclosed.”

Ford was also concerned about the apparent absence in Yamada’s lab notes and data of a record of an extraction control test to rule out contamination in the sample.

“He also made another very bad decision, which was that he didn't quantify the DNA,” he said. “The reason why quantification is so important is that the analyst needs to add the right amount of DNA at the amplification stage, where you copy the DNA over and over again, in order to minimize problems like artifacts [false readings caused by tests] in the electropherograms. I think he said he didn't quantify it because he didn't want to waste DNA. But it only takes a minuscule amount of DNA to perform the quantification – an awful lot less than the amount he wasted performing the amplification stage over and over and over again. In the end, he generated over 30 different DNA profiles from just one item of evidence. Without quantifying the DNA extract, it was like trying to play darts blindfolded.”

“It definitely looks like there is an element of the Texas sharpshooter fallacy going on,” Ford added, referring to the selective use of data to confirm an existing position. “I think that the best thing to do with Yamada's testing is to just simply say it's inconclusive … it doesn't mean anything. It doesn't have the capacity to exclude Chris [Payne], nor to include him.”

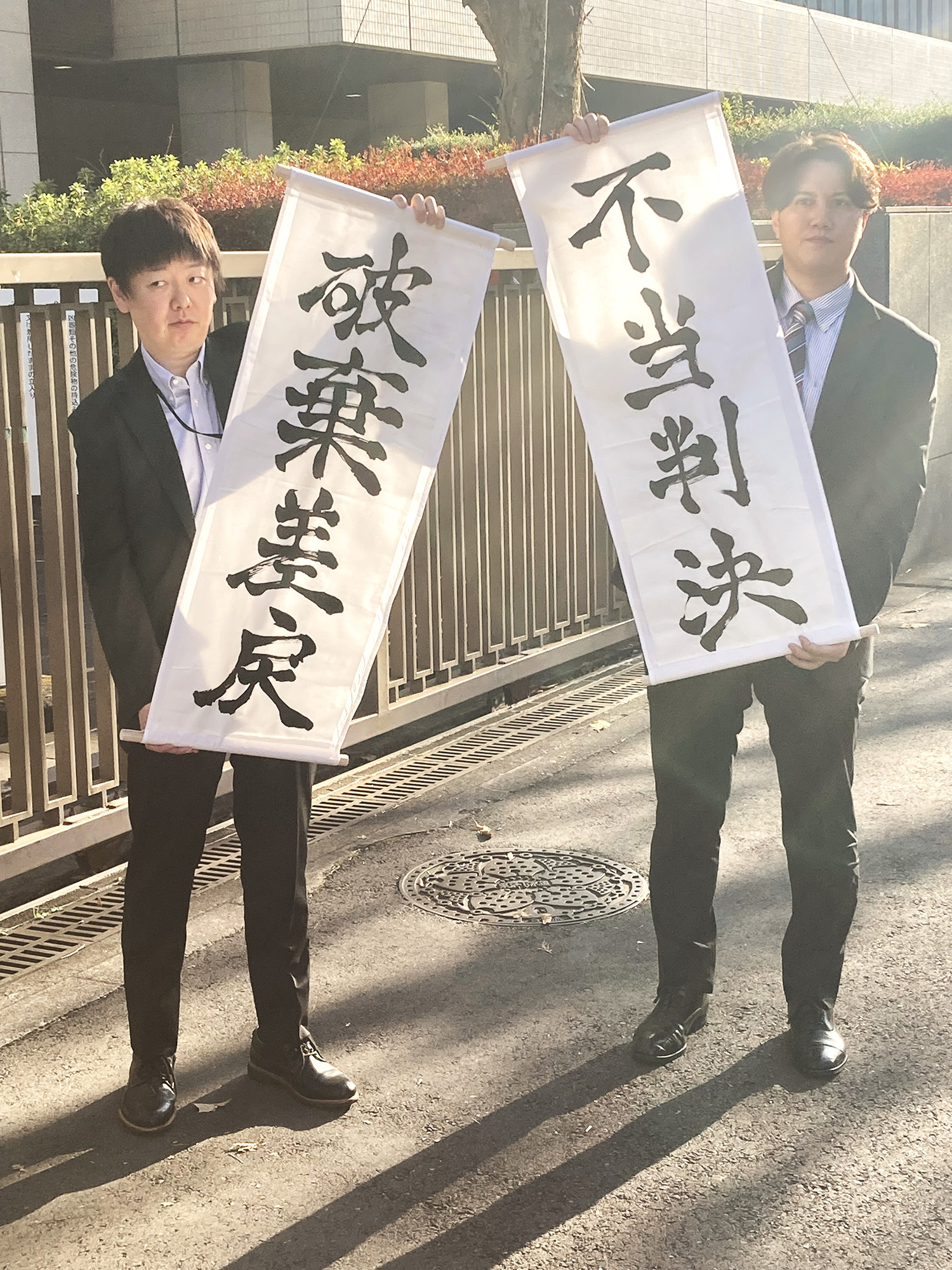

Ford’s findings were central to the appeal lodged with the Tokyo High Court, which on December 11 acknowledged there were issues with the DNA tests, overturned Payne’s guilty verdict and sent the case back to Chiba District Court for a retrial. However, it didn’t acknowledge Payne’s innocence or release him. He remains in solitary confinement at the Tokyo Detention House, the same facility that held Hakamada for decades, as well as former Nissan CEO Carlos Ghosn before his release on bail and dramatic escape from Japan.

Two days after the decision, Payne’s blood pressure spiked and he collapsed, according to his lawyers. On the morning of December 16, he vomited blood and continued bleeding from his mouth and nose. He then became delirious and had to be restrained and taken to the detention center infirmary. At the time of writing, he is in a cell equipped with surveillance cameras. Payne has now been held in solitary for nearly four years, longer than the sentence his public defenders told him to expect if he pled guilty and paid compensation to the assault victim.

His lawyers submitted a bail petition on December 15, arguing that Payne’s conviction had been overturned, his passport had been surrendered to them, and that there was no risk of him attempting to tamper with evidence or witnesses, as the only proof against him was the DNA testing.

Kouta Honda, who has led the campaign to free Payne, said, “For now, the focus is on proving Chris’s innocence, but that is just the first step. Next is reform of the Japanese justice system so that this never happens to anyone again.”

Gavin Blair has been writing about Japanese culture, society, politics, economics, crime, business and entertainment for more than two decades in publications in Asia, Europe, and the U.S., as well as reporting for TV and radio. He has authored five books, which have been translated into a total of six languages.