Issue:

January 2026

Japanese-American boy was just six when he was killed by the kempeitai military police in 1923

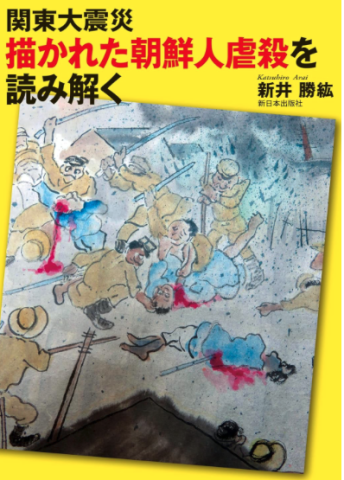

Throughout 2025 I continued expanding and updating my digital photo library, which led me to several sites related to the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and its aftermath.

The extrajudicial murders of Japanese socialists in the wake of the disaster made major headlines. Two days after the earthquake, the Tokyo Kempeitai (military police) failed in an attempt to take custody of Communist Party members when a platoon arrived at Ichigaya Prison with several escort vehicles and demanded that its warden, "immediately hand over all the defendants in the Communist Party Case". Fearing repercussions, warden Ohno refused to open the prison's gates to the MPs, sparing several dozen socialists from almost certain death.

Others, however, were less fortunate. On the other side of the city, the Kameido Incident occurred amidst a chaotic situation where hundreds of thousands of evacuees began pouring into the district on the night of September 1.

According to Koto Ward history, nine labor activists were arrested and detained by police between September 3 and 5, after which they were bayonetted to death by soldiers of the 13th Cavalry Regiment, whose cooperation had been requested by police. The soldiers disposed of the bodies, together with those of Korean and Chinese massacre victims, along the banks of the Arakawa drainage canal.

The Metropolitan Police Department kept the incident strictly secret, only making it public on October 10. Survivors' families, the Nankatsu Labor Association, and the General Federation of Bar Associations denounced the authorities, while the Japan Federation of Bar Associations demanded a truth-finding investigation and exercise of judicial power. At the time, however, the incident was deemed an act that occurred while under martial law, and the military's responsibility was dismissed, preventing the true circumstances from being uncovered.

Close to Yahiro Station on the Keisei Oshiage line is Kinegawa-bashi, a bridge that spans the Arakawa River drainage canal. In September 1923, large numbers of Koreans were said to have been killed nearby by jikeidan (vigilantes) while attempting to cross a bridge to escape fires.

It was not until 2009 that the Memorial Monument for Korean and Korean Martyrs During the Great Kanto Earthquake was erected on a small private lot facing the outer bank of the canal.

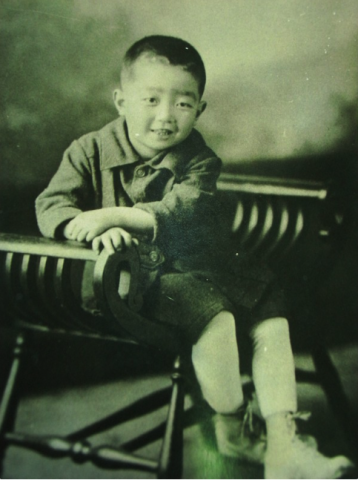

In addition to the thousands of Koreans, Chinese and Japanese socialists slain by vigilante groups, police and the military, my attention was drawn to the single American victim, a six-year-old boy named Munekazu Tachibana.

Born in Portland, Oregon, in April 1917, Munekazu was the nephew of Sakae Osugi, an outspoken anarchist who had already served a 30-month prison term for violation of Japan's draconian press laws.

More than two weeks after the earthquake, on September 16, kempeitai captain Masahiko Amakasu dispatched teams of soldiers to track down and apprehend the 38-year-old Osugi, who was finally spotted around 5:30 p.m., waiting with Munekazu while his common-law wife, Noe Ito, age 29, shopped at a greengrocer near their house.

The three were transported to the military police compound near the imperial palace. At around 8 p.m. Osugi was taken into a conference room and seated. Amakasu later testified at his trial that he walked behind Osugi and locked his forearm across his throat in a judo stranglehold, causing Osugi to die of asphyxiation. The process was repeated shortly afterward with Ito.

Two enlisted men then strangled Munekazu using a hand towel. That night, the three bodies, stripped of clothing, were wrapped in burlap, bound with rope and tossed down an unused well.

The forensic autopsy report, only made public half a century later, noted that Osugi and Ito had been severely beaten before being strangled.

At his court martial in October, an unrepentant Amakasu delivered a rambling soliloquy justifying the slayings. "In just 50 or 60 years," he harangued, "our country has achieved the level of civilization that took 500 or 600 years in Western countries. If anarchists are allowed to oppose the ways of our sacred land, it will lead to the ruination of the Yamato race. [These people] were like parasites in the body of a lion, and I could not allow them to carry on."

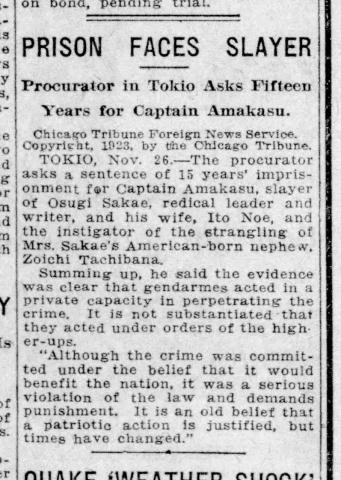

On December 8, the military tribunal sentenced Amakasu to a 10-year term of imprisonment. (The prosecution had requested 15 years.) Sgt. Keijiro Mori received three-year sentence, but three other enlisted men under Amakasu's command were acquitted because they acted on the orders of their superior.

A United Press dispatch under the byline of Clarence Dubose, dated December 12, 1923, reported that "Relatives of Sakae Osugi, the famous Japanese radical, who, with members of his family were murdered by military police after the earthquake, have sued the government for $50,000 in damages.”

It continued: "Gendarmerie Captain Amakasu and three non-commissioned officers who are accused of the murders are in prison, awaiting the outcome of secret investigations by the authorities.

"... each of the non-commissioned officers made 'confessions.' Each insisted the captain ordered him to kill the woman or the boy – but each non-com declared himself the murderer instead of his companions.

"Unsuccessful efforts have been made to involve the American embassy in the case, upon the claim that Soichi [sic] Tachibana, the murdered boy, was an American citizen. His mother asserts that he was born seven [sic] years ago in Portland, Ore, and his birth there recorded in order that he might be an American citizen. Later she returned to Japan.

"The American embassy has taken no official action in the case. The boy's mother has filed papers with the embassy which, she says, prove her claim that he was born in Portland.

"Said an embassy official: 'In the case, even of an unquestioned American citizen involved in trial in a foreign court, the law of that country must take its course, and we can only be interested in seeing that the trial is fair and the law impartially applied.'"

From the perspective of McGill University scholar Adrienne Carey-Hurley, Osugi’s murder could be seen as state-facilitated, if not state-sanctioned.

Four years after his death, Munekazu's father arranged for his burial at the Kakuozan Nittaiji cemetery in Nagoya. Munekazu's place of birth is inscribed on the tombstone horizontally in English. On the stone's reverse side, his father Sozaburo's bitter anguish is conveyed through the inscription in Japanese: "Massacred alongside Sakae and Noe Osugi by dogs."

It is uncertain when Munekazu's grave marker was pushed or toppled over, but it remained in that position for years and became overgrown with weeds. It was not until 1972 that a woman walking her dog discovered it and wrote a letter published in the local edition of the Asahi Shimbun.

The grave's rediscovery was news to Yukinori Tachibana, the grandson of Sozaburo's elder brother. The resident of Ama city told a reporter, "It's hard to believe now, but I wasn't told by anyone. I was surprised when I first heard of the grave marker in a newspaper, and I went with relatives to see it."

In 2023, a century after his death, Munekazu's grave was relocated to a smaller family temple in Ama. In addition to the original tombstone, a new stone marker reads:

Under the militarist regime, this tombstone was erected in the vast cemetery of Munekazu’s father, Tachibana Sozaburo, at Kakuozan Nittaiji Temple.

Half a century since then, a housewife out for a walk discovered the tombstone buried in the grass and reported it to a newspaper, bringing it to the public's attention.

In 1975, a group of volunteers established the Tachibana Munekazu Gravestone Preservation Society, and since then, they have held annual graveside services at the site. The decision was made to relocate the tombstone to Akitake (Ama City), Sozaburo’s hometown.

In memory of Munekazu's death, the tombstone will be preserved here forever to prevent such a tragedy from ever happening again.

2023 (Reiwa 5) Tachibana Yukinori

Last June 22, guided to the site by a friend's iPhone using GPS, I greeted the elderly Mr. Tachibana at his home and he directed me to the temple's cemetery, which is almost literally in his backyard. There, as far as I know, I became the first American to offer flowers and pay respects at Munekazu's grave.

Munekazu would have been 24 years old at the outbreak of the Pacific War. Had he remained in Oregon, he and his other family members would have been taken to the Portland Assembly Center in May 1942, and transported to a relocation camp such as Minidoka (Idaho), Heart Mountain (Wyoming) or Tule Lake (northern California). While incarcerated he might have volunteered for military service – the thousands of Nisei serving in the U.S. armed forces made heroic contributions to the war effort in both the European and Pacific theaters. Or, he might have remained in the camp and opted to be repatriated to Japan after the war's end.

On the other hand, had Munekazu been in Japan at the war's outbreak, he would almost certainly have been conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Army. But at least he would have had a chance to survive the war.

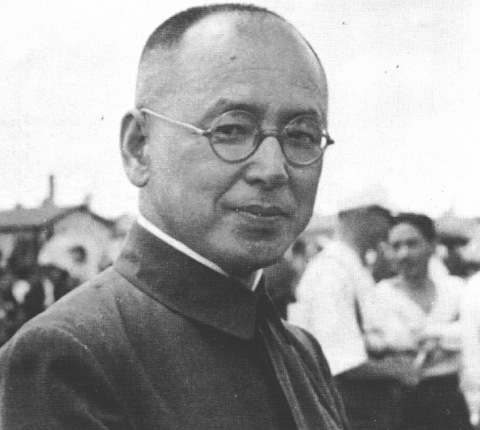

His killer, Masahiko Amakasu was quietly released from prison after just two and a half years, as part of a general amnesty to commemorate the coronation of Emperor Showa. Following a sojourn of 18 months in France, he traveled to Manchuria in 1930 and is believed to have been a key conspirator behind the Manchurian Incident, a false-flag bombing of the tracks of the South Manchurian Railway on September 18, 1931, that the Japanese Kwantung Army used to justify a military takeover.

In 1932, concurrent with the founding of the Manchukuo state, Amakasu was appointed director of the Security Bureau within the Manchukuo Ministry of the Interior.

Decades later, Amakasu's name had not been forgotten. TIME magazine's issue of September 5, 1938, reported that he been appointed vice-chairman of a Manchukuoan Good Will and Economic Mission of 26 members that had recently set out for a tour of Italy, the Vatican City, Germany, Rightist Spain, El Salvador, nations (in TIME's words) "which pretend there is such an independent State as Manchukuo".

"To go to such widely separated nations the good-willers necessarily had to pass through other countries, including England and the U.S. To 25 Manchukuoan glad-handers, British and U.S. consular authorities last week had readily granted visas. But neither Britain nor the U. S. would grant the honorable Mr. Amakasu even a transit visa. To Britain a murderer is still an 'undesirable alien.' To the U. S. a murderer is still guilty of 'moral turpitude.' To both, a murderer is a murderer."

On November 1, 1939, Amakasu became chairman of the Manchurian Film Association and spent the next half decade producing propaganda films such as Shina no Yoru (China Nights, 1940). He was still in that position in August 1945 when the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. After ordering the studio's entire capital to be distributed to its Japanese and Manchurian employees, he committed suicide on August 20 by ingesting cyanide. He was 54. His jisei (farewell poem), written in chalk on a blackboard in his office, read: Oobakuchi/ Migurumi nuide / Suttenten (The great gamble / Stripped bare / Utterly ruined).

Amakasu is buried in Sector 2 of Tokyo's Tama Cemetery.

A resident of Tokyo since 1966, Mark Schreiber has authored two nonfiction works about historic crimes in Japan.