Issue:

February 2026 | Letter from Hokkaido

Former residents of Russian-occupied islands turn to Hiroshima-style storytelling to keep their legacy alive

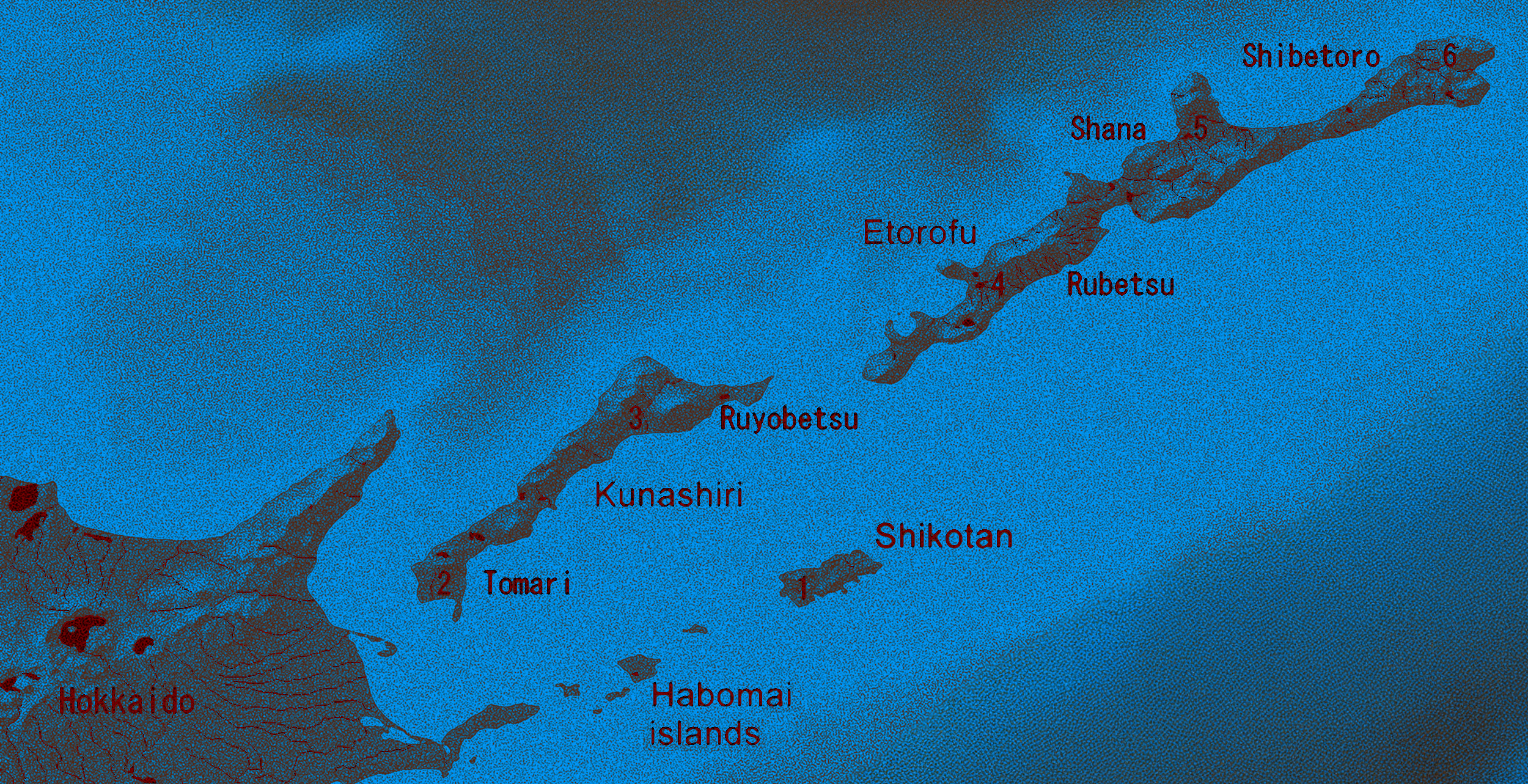

February 7 is Northern Territories Day, a tribute to residents of the four islands off the east of Hokkaido who were forcibly removed by the Soviet Union following its invasion in August and September 1945. The islands have been occupied by Russia ever since.

In recent years, the day has mostly involved sparsely attended gatherings around Japan to recall what happened and modest demonstrations by people holding placards and calling for the territories’ return.

A more formal event held annually in Tokyo ends with a plea to the Japanese government by former islanders to push for the return of the islands and to arrange for them to visit their family graves – something they have been unable to do since Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine four years ago.

In Hokkaido, though, former residents spend the entire year sharing their experiences and educating the public with talks at schools and to civic groups. Local governments sponsor the events to pass on their legacy to future generations and maintain pressure on the central government not to forget them and their cause.

But the number of aging islanders declines every year. There are now fewer than 5,000, with an average age of 90. Ony a handful are able to travel around Hokkaido, let alone to other parts of Japan, to tell their stories. In an increasing number of cases, their children have taken on the role, speaking to local primary and middle school children, greeting groups of visitors, and answering questions from journalists and researchers.

As of last year, just 33 former residents of Kunashir, Etorofu, Shikotan and Habomai, and 91 of their children, were registered with Chishima Renmei, the organization that represents them, to provide oral histories of what happened when Soviet troops landed on the islands.

To prepare for the day when none of the former islanders is left, Chishima Renmei is discussing the creation of an oral history training program modelled on one that Hiroshima has had in place for more than a decade.

Last autumn, former island residents and Renmei officials visited Hiroshima to learn how the city trains third parties to pass on the stories of hibakusha survivors of the 1945 atomic bombing, who are also dwindling in number.

Under the Hiroshima program, launched in 2012, trainee storytellers have to learn the city’s history and develop their public speaking skills. Graduates, many of whom have no direct connection to the hibakusha, greet visitors at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, working on behalf of those who can no longer pass on their experiences themselves.

A similar arrangement is envisioned for the former Northern Territories’ residents. Interested people would undergo a Renmei-approved training program by listening to the testimony of the remaining former residents and then orally conveying their stories when they and their families are no longer able to do so.

It’s a noble effort. But there are risks. The first is that it might produce graduates who don’t understand the difference between being a good oral historian and a bad stage actor, resulting in people becoming less, not more, interested in what happened.

The opposite is also a concern – that the program teaches students to give stilted talks that leave listeners wondering if it wouldn’t be better to watch old TV interviews with former Northern Territories’ residents themselves.

It is encouraging, though, that the islanders’ group supports the initiative, which is certain to generate a lot of interest in Hokkaido. Years from now, it’s easy to envision storytellers speaking to audiences with knowledge and confidence, and preserving the legacy of those who were forced from their island homes more than eight decades ago.

Eric Johnston is the Senior National Correspondent for the Japan Times. The views expressed within are his own and do not represent those of the Japan Times.