Issue:

February 2026

Tokyo’s official policy toward Israel contrasts with growing criticism of the Netanyahu government among the Japanese public

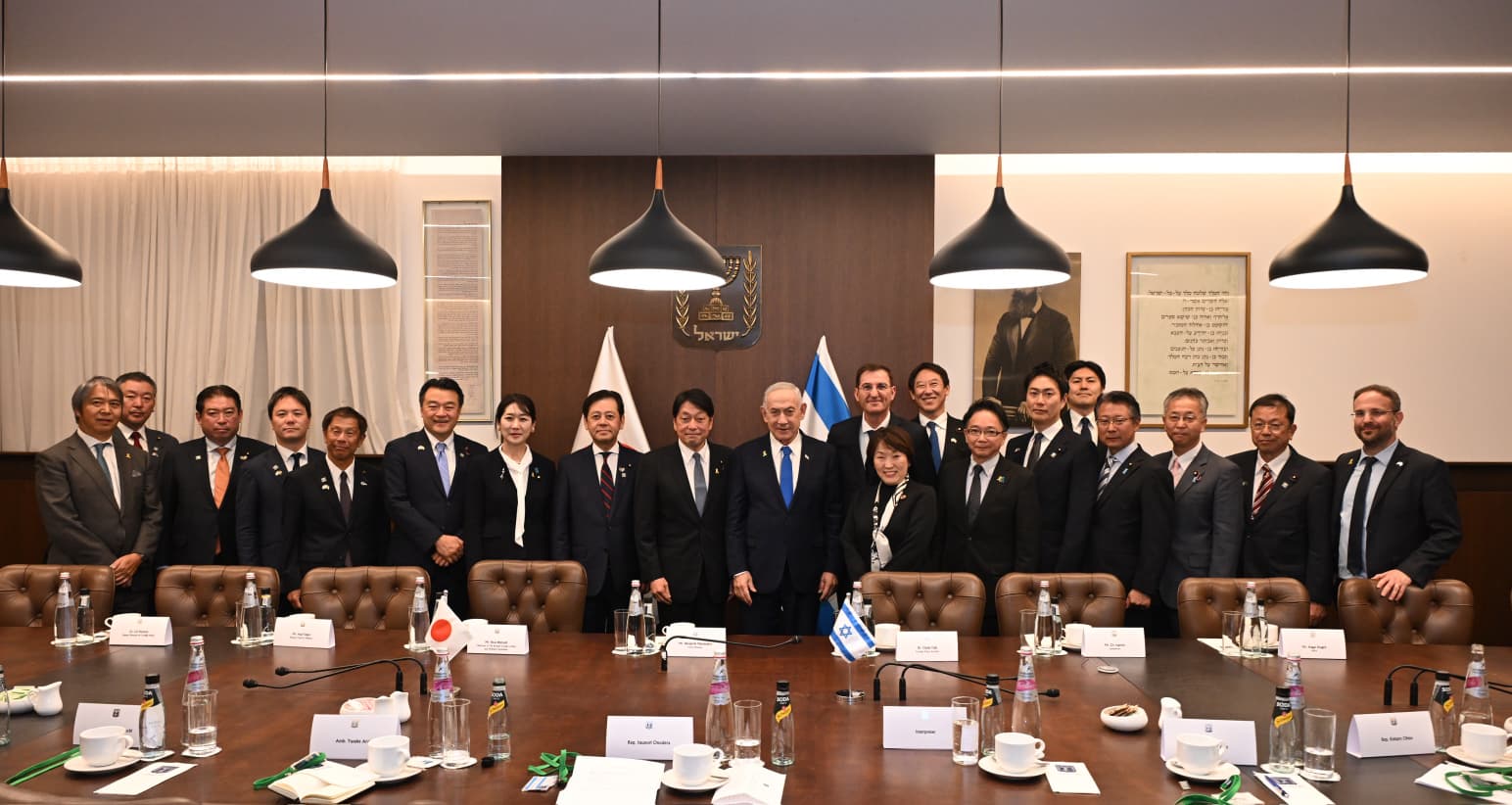

In January, Itsunori Onoda, a former defense minister and the current chair of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)’s commission on security, traveled to Israel with a group of MPs spanning the LDP, Ishin, and, surprisingly, a member of the left-wing Reiwa Shinsengumi. The group also included several independent MPs. It was Japan’s largest-ever parliamentary visit to Israel. Days later, the foreign minister, Toshimitsu Motegi, arrived in Israel on the first stop of a Middle East trip.

Motegi’s departure for Israel came only a day after the Tokyo Shimbun published a report detailing Tokyo’s continued purchase from Israel of security equipment worth more than ¥24 billion through no-bid contracts. This was happening at the same time as Israeli assaults on Gaza that have drawn international condemnation. Previously, the Japanese Communist Party’s newspaper, Shimbun Akahata, reported that in the FY 2026 budget proposed by the Takaichi administration, over ¥100 billion has been allocated for acquiring drones within the larger ¥9 trillion defense budget.

But just last year, reporting and cabinet officials’ statements had positioned Japan as ready to admit Palestinian refugees to Japan on humanitarian grounds, and possibly even go as far as recognizing Palestinian statehood. From a Pew Research Center survey finding that 79% of Japanese respondents held negative views about Israel, to multiple incidents of Israelis being denied lodging in Japan in reaction to Israel’s military invasion of Gaza, there appears to be a growing gap between official government policy and public perceptions of Israel.

Exemplifying this sense of widespread negative Japanese public opinion toward Israel, the frontman for Japan’s popular rock group, Asian Kung-Fu Generation, Gotch, posted on social media about reports of the Japanese delegation: “While some reports say that Japanese ruling-party lawmakers visited Israel and that Prime Minister Netanyahu thanked Japan for its support, this does not reflect the feelings of many people in Japan.

Many Japanese oppose the killing of civilians in Gaza and deeply wish for an immediate ceasefire and a peaceful future for Palestine. The actions of a small group of politicians should not be taken as the voice of the Japanese people.”

Has Tokyo’s policy towards Israel changed between the Ishiba and Takaichi administrations? Or has it continued, with increasingly anti-Israel set of sentiments amongst Japanese citizens acting as a foil?

Within the cacophony of policy and tone shifts from the Ishiba cabinet to the Takaichi cabinet last year, lost in the shuffle of reporting has been a sea change in cabinet ministers’ public statements about Israel and Palestine.

After the ruling LDP’s Taro Kono calling for a recognition of Palestinian statehood last August, the following month, the then chief cabinet secretary, Mitsunori Hayashi, explained, “it is a matter of when, not whether, to recognize [Palestinian statehood]” before Ishiba’s speech at the UN General Assembly. During his speech at the UN General Assembly last September, Ishiba criticized Israel’s role in creating a “dire humanitarian crisis in Gaza, including famine,” and pledged: “… [I]f further actions are taken [by Israel] that obstruct the realization of a two-state solution, Japan will be compelled to take new measures in response.”

The conventional wisdom for reporters and scholars looking at Tokyo’s policy towards Israel has been to place it within the broader context of Japan’s Middle East policy: characteristically risk-averse, focused on oil access, and, when possible, using diplomacy and aid to promote a rules-based, democratic worldview. Since the late Shinzo Abe’s second tenure as prime minister, Japan-Israel relations have deepened across the diplomatic, economic, and security sectors.

Takaichi has billed herself as the successor to the late Abe’s legacy, including quoting him during the announcement of her intention to dissolve the lower house on January 23. Takaichi’s security policies have been closely aligned with those of Abe’s. For this reason, Israel’s Ynet reports, “Israel’s leadership has warmly welcomed the election of Japan’s new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi.”

Citing Israeli officials’ and security analysts’ remarks, Ynet continues: “They view Takaichi’s outspoken support for Taiwan and her hawkish stance toward China and North Korea, along with her commitment to a U.S.aligned security backbone, as opening a new window of opportunity to enhance techsecurity and economic cooperation between the two countries.”

But when it comes to Israel, Takaichi’s stance within the LDP is not that much of an outlier. During the race for the LDP’s presidency last year, all five candidates openly agreed with the United States’ decision not to recognize Palestinian statehood. Furthermore, 2025 saw the relaunch of the Japanese Parliamentary Israel Allies Caucus, whose members are drawn from the ruling coalition, the LDP and Ishin.

Plotting these events on a broader trajectory, the apparent ambivalence of Tokyo’s policy comes into more precise focus. In a recent research article, scholars Rotem Kowner and Yoram Evron wrote: “Japan’s response to the war in Gaza followed a familiar script … From the outset, Tokyo sought to mitigate the crisis while steering clear of entanglement, adhering to its long-established posture on the Palestinian question ... By subtly distancing itself from Israel – however temporarily – and crafting a posture distinct from Washington’s, Tokyo deftly insulated its regional interests from unnecessary turbulence.” (Kowner and Evron, 2025: 31)

To this very point of “subtly distancing”, when Motegi visited Israel several weeks ago, foreign ministry readouts portrayed him as admonishing Israel for its settlements in the West Bank and stressing the importance of observing international law. Indeed, during the past two years, Japan has taken some unprecedented steps, including, in July 2024, sanctioning Israeli settlers in the West Bank for the first time.

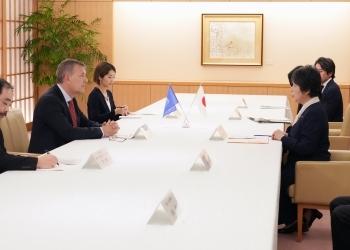

Between the readouts of Motegi’s visit and his signature on a letter decrying new Israeli laws about international NGOs, Tokyo has sought to present itself as aligned with multilateral, humanitarian consensus. The Mainichi Shimbun reported that Motegi had told his Israeli counterpart Gideon Sa’ar that Japan had “deep concerns” about the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. In contrast, NHK reported that Motegi had cautioned Sa’ar over ceasing “any unilateral actions that run counter to a two-state solution”.

But a quick scan of editorials and opinion pieces, such as the Asahi Shimbun’s AERA – which suggests Israel arranged the trip to redeem its international image – casts doubt on whether Tokyo’s balancing act is convincing a domestic Japanese audience. Separately, a January 15 editorial in the Okinawa Times warned that if “Japan shows a pro-Israel bias and loses its diplomatic balance,” the “Palestinian side’s hopes will fade”.

The most immediate consequence of the trip was the Reiwa Shinsengumi party holding a January 9 press conference explaining the party’s strong condemnation of Tagaya’s actions, as well as their resolute condemnation of Israel’s campaign in Gaza. At the press conference, Tagaya explained that while he had intentionally not told party officials of the trip and was aware that the visit “may be perceived as an expression of support for the Israeli government”, his intent was not to “support any specific government, policy, or military action”. Instead, he said: “I came to believe that without facing the reality of the conflict, seeing the site first-hand, and confirming the actual situation, there are limits to what politics can truly address.”

Even before the commission on security’s trip ended, Reiwa co-leader and MP Mari Kushibuchi decried the visit, arguing that reports of Netanyahu thanking Japan for “supporting Israel” risked Japanese NGO workers’ safety in Palestine by associating them with the Israeli government. Reiwa Shinsengumi notably held a “Stop the Gaza Genocide” rally on the two-year anniversary of the October 7 attack last year. Tagaya explained that while on the trip, “I wanted to ask [PM Netanyahu] questions about the genocide, but it didn’t happen.” On January 18, Tagaya submitted his resignation from the party.

The contrast between Motegi’s trip to Israel and the Onodera-led group visit was visually striking, and pointed to the occasionally ambivalent nature of Japan’s post-Abe ties with Israel. Notably, Abe sought to establish security ties with Israel while also developing the Jericho Agricultural Industrial Park with a US$100 million investment. While on his trip this year, Motegi visited Palestinian Authority PM Mohammad Mustafa in Ramallah and the nearby Jalazone refugee camp.

Online, Japanese netizens were quick to note that Motegi’s visit came days after meeting with Tomoko Akane, the director of the International Criminal Court (ICC). Notably, the ICC has issued arrest warrants for Netanyahu and former Israeli defense minister Yoav Gallant. In a striking juxtaposition, while Japan’s foreign ministry released a photo of Motegi standing beside the ICC’s Akane, the only photo they released of Motegi’s courtesy call to Netanyahu was of both Japanese and Israeli diplomats engaged in conversation at a table.

Part of the ambivalence in Japan’s Middle East policy is not a long-running tendency, but a careful negotiation of new geopolitical realities. Beyond balancing multiple partners’ interests, both Japanese diplomats and civil society must now navigate the closure of traditional avenues to support Palestinians.

While Japan’s humanitarian support for Gaza and the West Bank has traditionally operated through international NGOs such as the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), the past two-plus years since Hamas’s October 7, 2023, attack on Israel have challenged these programs. Japan initially suspended support for UNRWA in January 2024 following reports that UNRWA staff were involved in the October 7, 2023, attack on Israel. However, Japanese support resumed in April 2024.

But on October 28, 2025, Israel’s Knesset passed legislation banning UNRWA from operating in Gaza, East Jerusalem, and the West Bank. This came into force in January, with demolition crews tearing down the UNRWA headquarters in East Jerusalem this January.

Furthermore, new restrictions on international NGOs operating in Israel have directly impacted Japanese groups as well as international NGOs that have enjoyed Japanese support. On January 1, the Israeli government revoked the licenses of 37 international NGOs, which included two Japanese organizations: the Japan International Volunteer Center and the Campaign for the Children of Palestine. The foreign ministers of 10 countries, including Canada, Japan, and France, issued a joint statement on December 30 last year, decrying Israel’s new regulations and restrictions. Labeling the situation in Gaza “catastrophic”.

They said that 1.3 million people “still require urgent shelter support. More than half of health facilities are only partially functional and face shortages of essential medical equipment and supplies. The total collapse of sanitation infrastructure has left 740,000 people vulnerable to toxic flooding”.

The statement explained that a third of Gaza’s healthcare facilities would close if international NGO operations ended. NGOs who lost their accreditation include Doctors Without Borders, Oxfam, and the Norwegian Refugee Council.

The Tokyo Shimbun’s recent reporting underscores that despite shifts in public statements about Israel’s campaign in Gaza from the Ishiba and Takaichi cabinets, there appears to be more continuity than change in Japanese-Israeli ties. Since Israel’s ground invasion of Gaza began in 2023, Japan has seen a swell of protests opposing Israel’s actions, calls for Japan to support the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, and media coverage critical of Israel’s government and military. Already in 2024, over half of Japan’s prefectural assemblies passed resolutions calling for a ceasefire.

While there is scant empirical research to understand how prevalent negative sentiment towards Israel is, it simultaneously appears to have grown nationwide over the past two years, and yet has made scarcely a dent in diplomatic and economic ties between Japan and Israel. The continuity of policies between different cabinets may tell us much more about Japanese institutions and politicians’ relationship with voters than public statements and press releases.

Dylan O’Brien is an anthropologist whose research examines how cultural and religious differences are debated and understood in contemporary Japan. He has carried out multiple years of fieldwork with Jewish organizations in Tokyo and Kansai, and previously, organic health lifestyle communities across Japan. He completed his PhD at the University of California, San Diego, and teaches at several universities in Tokyo.