Issue:

February 2026 | Ripping Yarns (part 2)

Bra jokes, Dunhill cigarettes, and paranoia in 1980s North Korea

I was still in my 20s when I went to North Korea in May 1985. While I was hardly a worldly-wise Old Asia Hand, neither was I a gullible innocent when it came to Korea.

Already, I had lost any illusions about South Korea. A few months before I had been on the flight that took opposition leader Kim Dae Jung back to Seoul after years in American exile. At Kimpo International Airport he was violently separated from his entourage. Thousands of supporters lined the streets to Seoul, where he was promptly placed under house arrest. Massed ranks of riot police and plainclothesmen were a common sight and university campuses were often shrouded in tear gas amid mounting protests at the rule of former general Chun Doo Hwan, whose coup d’état in 1980 sparked the Kwangju Uprising, bloodily suppressed on Chun’s orders.

My knowledge of Kim Il Sung’s regime lacked first-hand experience, but nevertheless I had formed some conclusions. In Tokyo, foreign correspondents were inundated with South Korean propaganda about the North, and while scepticism was warranted, given the source, much of it seemed to chime with what we were also being sent by North Korea. It was irrefutable that an extraordinary personality cult had developed around Kim Il Sung since at least the 1960s. I was too young to have experienced the cults of Josef Stalin or Mao Zedong, but the images and language used to describe the Great Leader seemed to be of a different of magnitude. I was also aware of Kim Il Sung’s philosophy of Juche, usually translated as ‘self-reliance.’ It had considerable emotional and intellectual appeal to Koreans, given their tragic history of being preyed upon by great powers, but also meant that the North was falling far behind the capitalist economy in the South, and the dynamism unleashed in China by Deng Xiaoping, who had cast aside the autarchy of Maoism.

I knew too that since the 1950-53 Korean War, Kim Il Sung had ordered several terrorist attacks against the South, including the 1968 commando raid intended to kill Park Chun Hee, and which almost reached the presidential Blue House; the hijacking of a Korean Air Lines flight in 1969; and the Rangoon Bombing of 1983 that decimated Chun Doo Hwan’s cabinet and nearly cost Chun his own life. I was also aware of the invasion tunnels the North had secretly built underneath the Demilitarised Zone.

Still, I was unprepared for the sheer scale of the Kim Il Sung cult that met me in Pyongyang. It felt like witnessing the flora and fauna of the Galapagos Islands after following their own path of evolution, cut off from the outside world. Or the wonder felt by a boy on first encountering exotic plants that had grown to monstrous size inside a hothouse pavilion.

Chauffeur-driven tour

Each day my minder, Li Gi Baek, would greet me in the lobby of the hotel before we proceeded by chauffeur-driven Mercedes-Benz to various showpiece edifices in Pyongyang intended to illustrate the blissful life of Pyongyang citizens under the infinitely wise and fatherly nurture of the Great Leader.

Day one of the tour began with a North Korean joke, perhaps the only one ever recorded … The night before I had asked Mr. Li about North Korean humour, and this was the fruit of his research. “A man came to work with his arms stretched out in front and both hands cupped. His colleagues asked what had happened. He replied that his wife wanted him to buy a brassiere for her, and the only way he could remember the size, was to cup her breasts with his hands.”

Returning to the official itinerary, we gazed with appropriate awe upon The Arch of Triumph. Ms Kang Hei Gyung, the 24-year-old guide, informed us that it was 10 metres taller than the Arc de Triomphe (she was unaware that the original in Paris had been commissioned by Napoleon, a name with which she was unfamiliar). It was unveiled in 1982 on the 70th birthday of the Great Leader. Nearby was the Kim Il Sung Stadium, which at the time of liberation from Japan had been just a small sportsground. It was there on October 14, 1945, that a youthful Kim Il Sung first appeared in public. Next was the 170-metre-tall Tower of Juche, another 70th birthday present for Kim Il Sung. We climbed to the top where a red torch lit up at night, signifying a “new era,” according to Ms Chun Yun Hee, the 25-year-old guide.

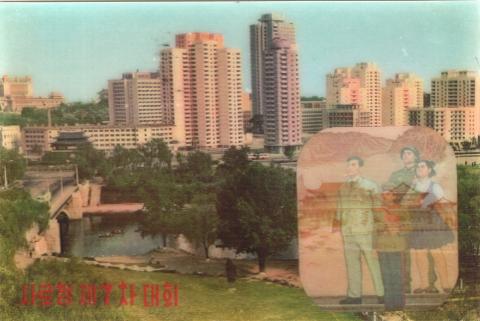

Pyongyang was pulverised by American bombing during the 1950-53 Korean War, and judging by the panorama, there were no buildings more than a few decades old. Most were housing for the 1.7 million population. Wide boulevards were eerily quiet. The only traffic was a few buses, and the Mercedes and Volvos used for official business. (The Swedish legal adviser whom I met on arrival at the hotel had told me that North Korea had paid for the 2,500 Mercedes limousines “up front, at the insistence of the West Germans”, but Swedish taxpayers were still on the hook for 83% of the 1,050 Volvos.) Lack of traffic was not the only reason for the purity of the air. Mr. Li said that polluting factories had been banished to the outskirts of Pyongyang.

The Tower of Juche was built from 25,550 pieces of granite, which Ms Chun said was “the number of days from the birth of the Great Leader to his 70th birthday”. I asked how she knew. “How do I know what?” “That there are 25,550. Have you counted them?” Both she and Mr Li burst out laughing. The mask had slipped, if only briefly. I asked Ms Chun what she did for relaxation. “In the evening, I meet my boyfriend, a junior clerk. We sometimes go to the People’s Palace, or to the Mansudae Art Theatre to watch an opera.”

I have scant recollection of the Korean Central History Museum in Kim Il Sung Square. My notes speak of a white marble statue of Kim Il Sung in the entrance, and the middle-aged guide, Ms Pae Chung Hee, saying that the great-grandfather of Kim Il Sung was personally responsible for burning the “General Sherman pirate ship from the USA when it sailed up the Taedong River.” (Like the “Black Ships” commanded by Matthew Perry that arrived off Edo Bay in the 1850s to force open Japanese ports, the General Sherman had been intent on opening the Korean hermit kingdom but was attacked and burned with fire ships in 1866. There is no independent record that Kim Il Sung’s grandfather played any part in the famous episode.)

“The key-word here is blackwhite … it means also the ability to believe that black is white, and more, to know that black is white, and to forget that one has ever believed the contrary. This demands a continuous alteration of the past …’

When black is white

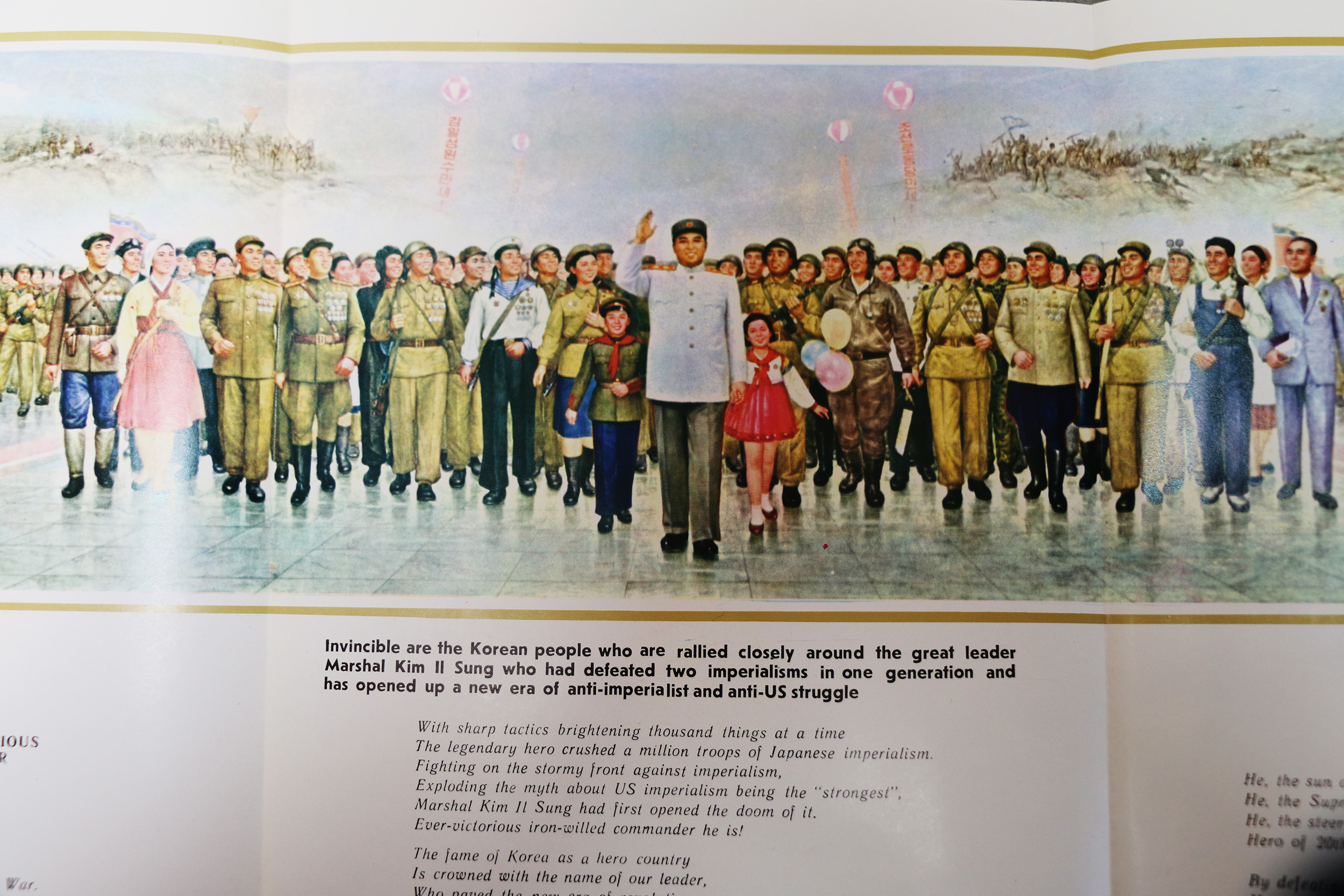

George Orwell’s words were at the back of my mind during an obligatory visit to the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum for it seemed his dystopian parody had been fully realised. The official guidebook already contained enough blackwhite to make my head spin. The museum was “dedicated to the immortal Juche-oriented military ideas and theories and brilliant strategy and tactics of the respected and beloved leader President Kim Il Sung, the ever-victorious iron-willed brilliant commander and eminent military strategist.” Hadn’t the Korean War that Kim Il Sung began turned into a military catastrophe - one from which North Korea needed rescuing by a two million-strong Chinese army?

The first hall inflated Kim Il Sung’s role during the “anti-Japanese revolutionary struggle” to Zeppelin proportions. A large painting showed him founding the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army in a pine forest clearing near sacred Mount Paektu, on April 25, 1932. Bordering Manchuria, Paektu is central to the foundation myths of Koreans and Manchus and was the official birthplace of Kim Jong Il in 1942 while his father fought valiant battles in the occupied homeland.

Stirring stuff, were it not for the fact that the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army never existed, and according to Soviet records, Kim Jong Il was born in Siberia. From 1932 to 1940, Kim Il Sung was a mid-ranking field commander in Chinese Communist forces fighting the Kwantung Army and the Manchukuo Imperial Army in Manchuria. From 1942 to 1945 he was a captain in the Soviet Red Army in the USSR, making only two forays into Manchuria, in 1941.

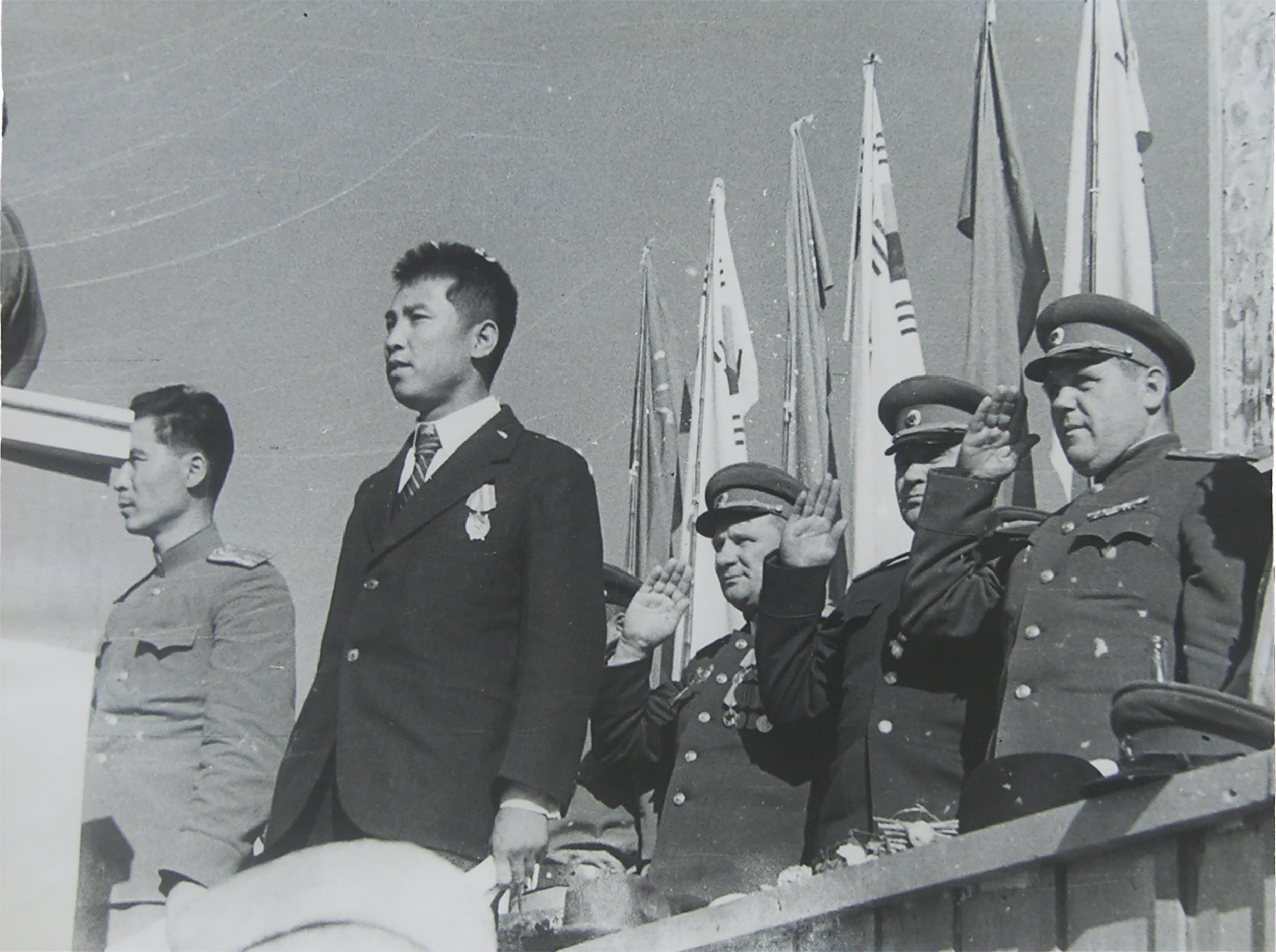

Likewise, Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule was heavily mythologised to give Kim Il Sung a leading role and erase that of his enablers. A day after the August 9 atomic bombing of Nagasaki, three U.S. military officers (among them Dean Rusk, a future secretary of state) were tasked with drawing up temporary U.S. and Soviet zones of occupation in Korea. Armed with a National Geographic map, they chose the 38th Parallel, partly because it included Seoul in the southern sector. According to the Pyongyang military museum, the “U.S. imperialists illegally occupied South Korea under the cloak of so-called liberation”, conveniently ignoring the North’s liberation and occupation by the Soviet Red Army. In its baggage train was Kim Il Sung, handpicked by Josef Stalin to lead an Asian communist satellite. He introduced himself at the Pyongyang sportsground on October 14. Standing right behind him were three Soviet generals, their images later removed in a doctoring technique acquired from Stalin’s USSR.

The historian Bruce Cumings provided a much-needed corrective to the sanitised version of the Korean War that held sway in the West well into the 1980s, pointing out all the provocations by the South’s bellicose strongman Syngman Rhee, major rebellions like that on Cheju Island that were brutally crushed, and numerous atrocities carried out by South Korean troops and armed thugs, sometimes abetted by U.S. forces.

Acknowledging all of this does not detract from the stark fact that the Korean War was launched by Kim Il Sung, after he received the go-ahead from Stalin and Mao in meetings from March to May of 1950. The central lie told in the North’s war museum is that it was the “U.S. imperialists and their lackeys Syngman Rhee puppet clique” who “started at last a villainous armed invasion on June 25, 1950”. At noon on that day, 150 Soviet T-34 tanks roared across the 38th Parallel at the head of about 100,000 North Korean troops. In a couple of days, they had reached Seoul. By August, the North Koreans had pushed South Korean and UN forces – the U.S., the British Commonwealth and a few other nations – to within a large rectangular perimeter around the southern port of Pusan.

En route there in July, the North Koreans had routed the American and South Korean troops in a battle for the strategic city of Taejon. The victory is heroically depicted in huge panoramic paintings in the museum. “I myself took part in this battle and killed more than 40 American soldiers,” Lt. Col. Li Roh Su of the Korean People’s Army told me. Then a 23-year-old company commander, he said he also fought against British troops, in August, near the Pusan Perimeter.

I asked Li what he knew of life in Seoul. “Capitalist millionaires are very happy and have a very rich life, but the lives of poor people are very miserable,” he replied. Had he heard that the streets of Seoul were clogged with cars? “Obviously, they must belong to owners of companies or senior government employees. I read in newspapers of the terrible death toll from car accidents in the USA, and the terrible pollution. Here we have no such problem.” What about television sets and telephones? “Most people in Pyongyang own a TV. There are only public telephone booths, no private telephones. At present, all telephones are used only for work and official business.”

North Korean hubris allowed Douglas MacArthur the chance to pull off the brilliant amphibious landing at Incheon that turned the tide of the war. Seoul was liberated and U.S.-led UN and South Korean forces rolled the North Koreans back over the 38th Parallel. MacArthur’s forces then pushed further north, taking Pyongyang, and reached almost as far as the border with China. It was MacArthur’s turn to be blinded by hubris, as the Chinese People’s Volunteers made a lightning advance across the Yalu River and drove the Americans, South Koreans and UN allies back to the 38th Parallel, where the war had begun, and which remains the heavily militarised border between North and South to this day.

Nowhere in the museum was there any mention of this decisive Chinese contribution that spared Kim Il Sung’s neck. Like that of the Soviet Red Army in 1945, it had been comprehensively erased from North Korean works of history.

Tight jackets and bow ties

Kim Il Sung’s birthplace in Mangyongdae, 10 kilometers outside Pyongyang, has become a shrine visited by millions of North Koreans. The thatched farmhouse and its outbuildings were built by the great grandfather who hadn’t really burned the General Sherman. A carefully deformed ceramic jar was on prominent display, to exemplify the family’s poverty, as they couldn’t afford to buy one with a normal shape. The concrete floor was painted brown to resemble beaten earth.

Elements reminded me of how the Nativity of Jesus has been portrayed in Christian churches. It came as no surprise when I later found out that Kim Il Sung had been born into a Christian family and his mother had been particularly devout.

The 13-floor Children’s Palace has huge theatres for performances. All the boys and girls I met had painted faces. The boys were trussed up in tight jackets and wore bow ties. The choir sang best wishes to the president on his foreign trips, and in one catchy number that had me reaching for a handkerchief, recalled a three-hour visit that Kim Il Sung made to the Children’s Palace one New Year’s Eve: “We wished it would never stop, we would like to be with our president night and day. We long to hear what the president says. Now we always feel as if we are with our president, and we are always happy.”

On the ground floor, boys were studying car mechanics. Thoughts of Kim Jong Il on the wall exhorted them to “learn mechanics to fulfil their duties to the country”. In a boxing class, the Dear Leader, who later became pudgy and sickly, urged them “to build a strong body”. In an art class, most of the students were copying with meticulous draftsmanship busts of revolutionary heroes. Seven-year-old Ryon was making a perfect drawing of a pyramid and a ball but could not draw for me the face of his mother. In biology, 15-year-old girls were dissecting frogs and suspending their hearts from pulleys to measure the heartbeat on a simple oscillograph. A model train class was, according to my guide, “to raise the appreciation of the national railways and inculcate a sense of responsibility for their upkeep”.

In Pyongyang’s biggest kindergarten was a room filled with hundreds of stuffed wild animals – I counted eagles, giant turtles, bears and wild cats, as well as pickled fish in jars. Who was responsible for this wildlife slaughter, I wondered, and why was it considered beneficial to young children? “Dear Leader Kim Jong Il said children in Pyongyang don’t have much chance to see such species as they are far away from the sea and mountains., so he sent such specimens,” explained Jung Kum Sum, a female teacher.

The dining room had marble columns and crystal chandeliers. “Thank you, Marshal Kim Il Sung, the respected father,” read a sign on a door. In a beautiful indoor swimming pool, happy children splashed around an inflatable dinghy. A smiling teacher joined in.

I was shown a Mangyongdae history class for toddlers. Eager faces gathered round a huge plastic model of Kim Il Sung’s birthplace and adjoining park which they had visited the previous day. Each young child was made to recite a lesson. Example: “When our president was a child, he bred a cow to help his father. Every day he was reading, so the cow escaped, because he was reading and studying so hard.”

In a vast indoor playground, the kids jumped inside an electric train which ran along one wall. On seeing a visitor, the children quickly approached, clasping their hands and smiling, the same routine as at the Children’s Palace. I asked why every member of an infant choir wore eye makeup and other cosmetics. “They had gone outside to perform at a construction site,” Ms Jung replied. “That’s why they were ready for you.”

‘Palace for the people’

With Mr. Li leading the way I descended into the Pyongyang Metro. Modelled on the Moscow Metro built for Stalin as a “palace for the people”, many of the stations had fluted marble columns, crystal chandeliers and polished granite floors. Kwangbok (Restoration) Station was dominated by a huge gilt seated statue of Kim Il Sung, supposedly writing the Ten Point Programme for National Unification and Future Government Policies when he was 23 years old. Landscapes on the walls depicted “where the president fought the Japanese”. The next station, Gungkuk (Construction), had a painting of Kim Il Sung in shirtsleeves, surrounded by adoring peasants eager to work on a land reclamation scheme. Another painting at Hwanggumbul (Golden Field) showed Kim Il Sung standing in a field of golden rice and mobbed by doting farmers. This time there were no chandeliers, just gaudy illumination.

I emerged into daylight, ready for more spiritual uplift. The Pyongyang June 9 Girls’ Middle School got its name after the day the Great Leader dropped by for an inspection visit. “We’re not emphasising ideological education, the principal, Mr. Kim Mong Chu, assured me. This was not my impression during a history lesson I observed about the Korean War. “Because our president personally took responsibility and prepared strategy, he could repel the enemies immediately. This war was fought not by the military but by the whole nation,” the female teacher told the class. Thirty children shouted out “We agree.” Teacher: “If our people had not been fully mobilised, we could not have won the war. Anyone know what date we entered Seoul?” Students: “Fourth of July!”

Another room was filled with stuffed animals, as well as trays of historical relics, not all of them genuine. “Every school gets them,” I was told. Walls everywhere were daubed with exhortations from Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, and there was a painting of the father and son. Inevitably, the girls in a needlework class were learning how to stitch the Great Leader’s profound thoughts: “Women should learn household work not just for the family but for society.” Wall posters depicted female guerilla fighters doing the sewing for their menfolk in the forests. Being Saturday afternoon, we were entertained by a school orchestra of choir, zither and accordion. The girls were dressed up as if going to a ball. The repertoire included Bumper Harvest in Gumgang Village. For light relief, we went to the circus in the evening. The acrobats and tightrope walkers were highly accomplished, but the clowns left me cold. Their routines were crude satires of corruption in South Korea, featuring Chun Doo Hwan and his wife, and policemen. I preferred Mr. Li’s joke about the brassiere.

Before retiring, I switched on the TV in my hotel room. One channel was Soviet television, a cabaret of songs and conversation, all in Russian. On the other channel was a black-and-white drama of a young couple having fun at the Mangyongdae amusement park. It was followed by yet another tale of the epic revolutionary struggle of Kim Il Sung.

30 million books

A colossal white statue of Kim Il Sung reading a book greeted visitors to the People’s Grand Study House. The floors were of inlaid marble mosaic, and there were marble columns on each of the seven floors. I was told it housed 30 million books, but when I asked to see the 5th floor section on politics and religion, the 27-year-old guide said it was “impossible”. Instead, I was taken to a music room, where the gramophone collection had such classics as “We live with the President in our hearts”.

In the middle of the day the itinerary was suddenly blank. In the hotel lobby I grabbed an Italian businessman who had a joint venture to manufacture shoes. We walked out and dived into one of the Metro stations I had been shown the day before. The chandeliers were switched off and there was only emergency lighting. It felt like being in an underground cellar rather than a brilliantly lit palace. Martial music was playing inside the dimly lit trains. The passengers had sullen faces and there was no talking or laughing. We got off at the third stop. Again, the station was dark. The only distraction was a billboard for the Rodong Sinmun, organ of the Workers’ Party of Korea. Soldiers seemed to be everywhere. A stern woman’s voice issued from loudspeakers.

Outside the Metro station were a few shops. None had fresh meat or fish. One store had spring onions and lettuces. Another sold dried fish and kale. A soldier with a machina gun was patrolling the street. At an amusement park, near the Pyongyang zoo, we found more soldiers with machine guns. My minder tried to laugh it off when I recounted what had happened. The Metro stations were probably saving electricity. The soldiers were off duty. But why were they carrying machine guns? Mr. Li had no answer.

At my request, a visit to a worker’s apartment was arranged. Lee Wol Kae was a housewife who did part-time knitting piecework. Her son had a scholarship to an international relations college and was studying English. When he reached 27, he would follow the Great Leader’s order and marry. His girlfriend was doing military service. Mrs Lee said meat and chicken were rationed but she had no complaints. “I never dreamed of having such an apartment,” she said. “Last April, I went to see relatives in Hamkung for a holiday.” I asked what she knew of life in Seoul. “I have heard something through the news media. Many people are suffering under harsh conditions, such as a man who sold his eyeballs to pay for medicine for his sick parents. I think we are much happier than that, as we don’t pay anything for our health and housing.”

Mrs Lee displayed two separate portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, and one of them together. “We are honoured and proud of Kim Jong Il. He is known to us more and more. We believe in his leadership. He’s providing housing. Through his guidance he is personally taking care of workers. I believe that everything I hear on television and read in the newspapers is true.”

Kang Sok Ju, vice chairman of the Korean Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, was put up for an interview. After extolling the virtues of Kim Jong Il and why he was supremely qualified to succeed his father – “developing and enriching the theory of Juche,” “many noble virtues,” “always shows love and affection for the people” – Kang stuck it to class enemies and the running dogs of South Korea. “Of course, we oppose any influence and any elements of the bourgeoisie” – and yet, I couldn’t help noticing, he smoked Western cigarettes, was dressed in a sharp suit, and drove around in the back of a German limousine. South Korea was “full of disturbances” and by hosting the Olympic Games in 1988, hoped “to gain recognition as the sole state on the Korean peninsula”.

Interference by the United States and its military presence in South Korea was the greatest stumbling block to Korean reunification, Kang said. If the United States were to withdraw its troops, a “non-aligned and neutral confederal state” could be created that would preserve both capitalist and socialist systems “for the time being”. I pressed to meet someone more senior and was granted a meeting with former foreign minister Ho Dam, a trusted confidant of Kim Il Sung who later that year was sent on a secret mission to Seoul. His official role when we met was director of the Unification Front Department.

“We want to have as many friends as possible,” Ho began. “You have been told we are bellicose and all the time attempting to invade the South. But we have turned Pyongyang into a modern city, and we do not want our peaceful construction destroyed by another war.” Allegations of North Korean complicity in the Rangoon bombing were “completely baseless,” he averred. Ho’s fixed smile became discomfiting. He was immaculately tailored, he wore tinted spectacles and sported a solid gold watch. When he offered me a cigarette, it was Dunhill International. I kept thinking of a shop selling only plastic shoes and the near-empty shelves in a Pyongyang supermarket.

Before being given an exit visa to leave North Korea, I was told to first pay a hefty bill, in cash, for the chauffeured limo that had taken me around Pyongyang. When the Air Koryo plane touched down at the old airport in Beijing I felt like kissing the tarmac. I checked into the airport hotel but then discovered that I had left the key for my Samsonite suitcase in Pyongyang. I took the case in a taxi to a Beijing market and had a replacement key made in a jiffy. Back at the hotel, I at once ordered Peking Duck. As Orwell might have said, some communist states are more equal than others.

In the runup to the Seoul Olympics, a bomb exploded on a Korean Air flight in November 1987, killing all 115 passengers and crew members on board. Kim Hyon Hui, a North Korean agent, confessed to planting the bomb. It was around that time that I found myself interviewing a radical student leader in Seoul National University who had swallowed North Korean propaganda hook, line and sinker and was transcribing and printing broadcasts from Radio Pyongyang. He told me that he refused to believe what the South’s military government, “propped up by the American imperialists”, was saying about North Korea. What Kim Il Sung was doing was defending Korean independence, he insisted. I tired of trying to dissuade him. “You really have no idea,” I said in exasperation. “You haven’t been there.”

Peter McGill was the youngest-ever president of the FCCJ. He was based in Japan for almost 20 years, working as the correspondent of the Observer and other publications. He now lives in the UK.